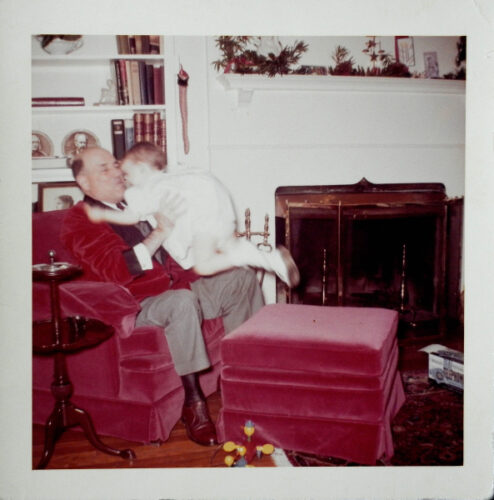

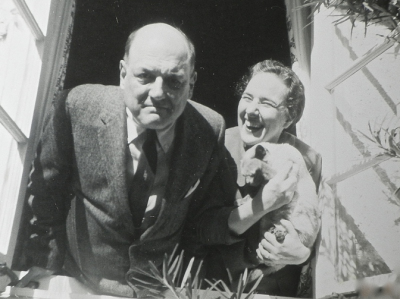

I’ve been procrastinating for years writing this story down, mainly because I’ve written it already, years ago, on a 1990 floppy disk, the real floppy kind of floppy disk, that no one seems to have the machinery to access anymore. But someone I care about is feeling the loss of a loved one today, a loved one who sounds as magical to them as my Tisolay was to me. Most people aren’t blessed with the gift of leaving this earth peacefully and painlessly at 99 in their own home, flirting to the end, like my Tisolay was. Nor are those left behind given the luxury of years for closure, in which to lavish a thousand ‘I love you’s and ‘thank you’s on their loved ones while they still can, like I was. So in honor of my friend and the one she’s missing today, I bring the procrastination to an end.

~~~~~~~ 🎶 ~~~~~~~

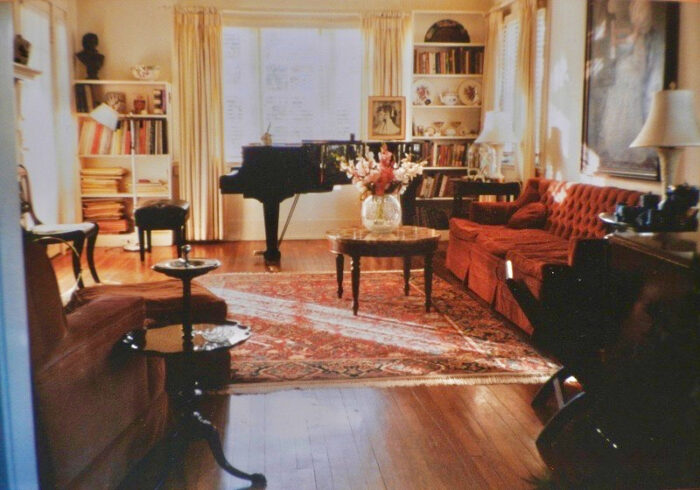

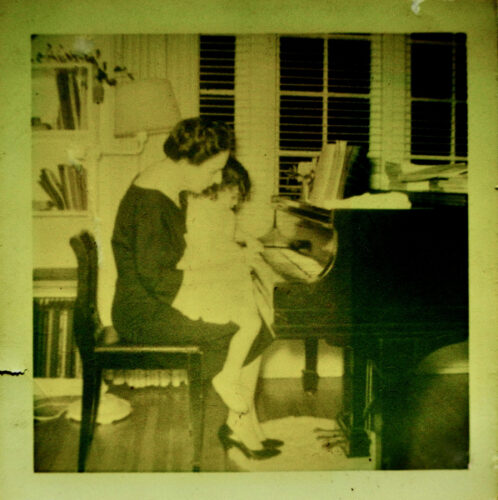

One morning in the Fall of 1963, Tisolay, my grandmother, kissed my grandfather goodbye at the door as he left for work, then as per her routine, went straight to the piano for a couple hours of practicing.

She rarely practiced while Granddaddy was at home to hear all the stop-starts and endless repetitions of problematic passages that practicing entails. All Granddaddy heard was the finished product, usually after dinner when he’d go sit in his chair in the living room with a pipe and listen to Tisolay play for him.

I don’t know whether she first noticed that the mockingbird in the chinaberry tree out front was singing along with her, then thought of Granddaddy’s upcoming birthday, or whether she had already been pondering what to do for his birthday when she noticed the bird outside. But the idea came to her to make a record of her playing along with the bird for his birthday.

She hurriedly set up the reel-to-reel tape recorder, unwinding miles of wire that went to two separate stand-up microphones, one of which she dragged all the way out to the foot of the tree. She put the other one next to the piano, then sat down to play everything she could think of; a Debussy, a Moszkowski, a Schumann, 2 Chopins… I don’t remember what-all. She would later tell us that she was worried the whole time that if she paused for anything, the bird would get bored and fly away. It never did, though.

Tisolay always did have a way with birds, particularly mockingbirds and cardinals. With every new season, there was usually a mockingbird in the crepe myrtle tree outside the kitchen door whom she’d talk to and put seed out on the back bannister for. They’d come regularly, and once, she put a handful of birdseed on the floor inside the door, then went to the far end of the room and sat quietly. In time, for a few moments, it came in and ate.

She taught me the songs and calls of mockingbirds, with their ever-changing assortment of song bits, whistles, clicks, buzzes, whatever… and cardinals who were always calling “Marguerite? Marguerite?” and “What cheer, what cheer?”. She taught me how to tell the ages of the season’s new babies by how disorganized their song still was.

Over the years, we found several baby birds who’d fallen out of their nests and raised them, all mockingbirds except for one nighthawk. The last one we raised was found under a tree by a group of teenagers in a long-term residential adolescent unit in the yard of a psychiatric hospital where I worked. Its head was bald except for a ring of fluff around its head, like my grandfather. And it was very weak, barely conscious, what little energy it had going into periodic spurts of gaping-mouthed begging for food. Who knows how long it had been out there.

The kids knew that just bringing it inside, let alone trying to raise it, was a health code violation 6 ways to Sunday, but I said I knew someone who had raised lots of baby birds. So we snuck it in past the head nurse, found a box for it and lined it with socks, got several drops of water into it, and at the end of my shift, I took it to Tisolay’s. It was a bit more alert and sharp-eyed by then, and its expression reminded me of one of my favorite shots of my grandfather. My next shift on that unit, I brought the photo for the kids to see, and they agreed to let me name it Percy Henry.

A few times over the next few weeks, I’d get the kids around the nurses’ station, then call Tisolay and put her on speaker-phone so she could tell them about the bird; how he’d grown, which feathers were coming in, what a ‘piggy’ he was at meal time. Always comfortable performing in public, she put on a show of charm and mischief for the kids. When it was old enough to be shown the outdoors again, she described what my face looked like when tiny bird claws were skittering back and forth along my bare leg, outstretched on the garden recliner. When we were teaching it to fly, she described its reluctance to let go of her finger, and when it did, how it hated landing on the sharp blades of grass with nothing solid to curl its feet around.

And when it was a strong enough flier, she described how it would avoid landing, fly back up and land on her head instead, and how it started doing that inside even though grass was no longer an issue. They thought she was pulling their leg, so she had me take a polaroid.

Predictably, a few of the girls asked if the bird ever pooped in her hair. I think they wanted to throw her off balance, making her dance around indelicate language, but the cheerful answer from this gentle, delicate woman dissolved even the diehard “too cool for school”ers.

“Oh, you just wait for it to get hard, then you can pull it right out.” When a chorus of “Eeew”s arose, I know I saw the mildly-disapproving head nurse grin just before turning her face away.”

I was still in graduate school, rotating across all units, and I never got the chance to tell them that Percy, after he finally took the flight that he never returned from, often dive-bombed Tisolay’s head out in the garden that first year, touching her hair but never again landing.

~~~~~~~ 🎶 ~~~~~~~

A-n-y-w-a-y. After 45 minutes or so at the piano, she came to the end of a piece and saw BadBoy, their Siamese cat, come strolling in from the dining room. Badboy always had a lot to say, and he did so in a deep baritone voice that always rattled with his purring. When he started talking to her, the microphone was a bit startled. When she picked him up and brought him to the mike, it nearly knocked you over. She gave Granddaddy a sweet birthday message in her gentle voice, then she cooed, “and minnie cat loves you too” and started squeezing purrs out of him, which sounded a bit like an idling diesel truck being revved over and over.

She took the tape someplace to have a record made, then went rooting through a McCall’s magazine where she’d seen a picture of a little 5-yr-old girl with brown hair down her back, like mine, sitting in the doorway of a kitchen with a green-and-white-tile floor, like hers, with a redbird on her finger. She pasted it to the record jacket with a long velvet ribbon around the edges and gave it to him when we were all over for dinner. Granddaddy played it for us, everyone was charmed, and that was supposed to be the end of that.

~~~~~~~ 🎶 ~~~~~~~

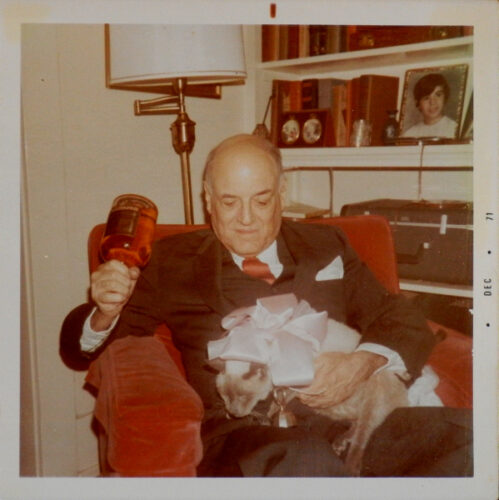

BadBoy was always part of Granddaddy’s birthday because they had the same birthday. The fact that he had to share his birthday with a cat was an indignation he often played to the hilt. The yearly bottle of Chivas, held like a club, played a role in the ritual more than once.

It was weird; Granddaddy wasn’t crazy about cats, but they loved him. BadBoy’s successor, Ping Pong, would climb up his shoulder when he was in his wing chair reading, stretch out across the back of his neck, and go to sleep. Rarely evenly balanced, he usually came slowly sliding down, head first, until Granddaddy had to cup Ping Pong’s head with one hand to keep him from falling into his lap and waking up. A hand that had previously been occupied holding whatever Granddaddy was reading, which meant adjusting to a single-handed grip. When that was a newspaper, there was always a long rustling of ungainly unfolding and refolding, and an audible, irritable grumble with the occasional intelligible bit… “never in my life”, or some such, under his breath.

Anyway, not long after Granddaddy’s birthday, a good family friend was over for dinner one night, a Jesuit priest, the dean of the music school at Loyola who’d hired Mother a few years before to teach piano, and he heard the record and asked for a copy. Tisolay was horrified . . . oh, no, it wasn’t her best playing, she was rushing, scared the bird would fly away at every pause, there were mechanical buzzes, amplified fumblings, and thuds followed by mid-piece pauses to adjust a fallen microphone, etc. Granddaddy must have been the one to have a copy made for C.J., with Ti’s personal message edited out, but the cat and the “and minnie-cat loves you too” still in.

C.J McNaspy. Though he was dean, he still taught a class called Music as Value which was a prerequisite for all music majors, something about finding the voice of God in music. He had a freak gift with languages, though… spoke several dialects of Russian as well as French, Spanish, Latin and I-don’t-know-what-all, so after a few years, the Jesuits decided to send C.J. to Paraguay, the first of several places around the world, to start a radio show along the order of his class, about music of every culture being the voice of God. It wasn’t until several years later that Tisolay found out that he had a copy of her mockingbird record and played it as one of the first things whenever he was moved to a new location. Over international airwaves. She was absolutely mortified. It became a family thing to tease her about it, because it was imperfect and human and magical, and it SO didn’t matter that her playing had not been concert-quality that day.

Okay. Fast forward to my freshman year as a music major at Loyola. C.J. is teaching again at Loyola, back in Louisiana because he’d requested to be nearer his elderly mother in her last years. So, I’m sitting in the auditorium waiting for C.J.’s first class of the semester to start, looking at the tape recorder, slide projector, and screen set up down in the front and sensing that this wasn’t going to be a regular Music as Value class like it used to be. I was right; it was a rollicking ride across the globe to places where he’d found God’s voice in strange musical performances and tribal ceremonies, in animal sounds and weather phenomena, from atop a squishy-humped camel and God-knows-what-all… you name it. When C.J. finally walks in, he goes to the tape recorder, and without introducing himself or even saying hello, he starts the tape machine, filling the room up with the loud chirping of a mockingbird soon joined by a Chopin étude. It didn’t bring me to tears the way it does now; Tisolay was still alive and well, and would be for many more years. But it was then that it occurred to me how others saw this thing, this family story that was just a regular thing to me, an episode in our family life. When he ended it, he said to everyone that he had the privilege of having in his class the granddaughter of the woman who made the record with the bird, and he asked me to stand up. It was a very dear, quietly proud moment for me.

I’ll leave you with this postscript. In later years, when Loyola beefed up their acoustics department with equipment to study the science of sound, my mother gave the tape to them to analyze, and see if the bird’s singing were actually following along with her. Of course it was. And now, writing this almost 60 years later, I think “duh, that’s why it’s called a mockingbird”.

As usual, thanks so much for visiting my little world and taking my grandmother into your hearts..

Dear Laura,

What an extraordinary and lovely story, in pictures, words, and song.

I can almost hear it. Any chance the duet is available digitally?

Imagine what a treat to click on a link and listen to it.

Thank you for sharing your loves and life story with us.

Always,

Nicole

I’ve come upon your story after hours of listening to the mockingbird in my tree out front; and it is now 12:48am. My mockingbird must be on at least his 38th song for the evening. And not knowing much or actually anything about mockingbirds, I delved into a mini-research Google session. I have found many facts and much humor about this bird, but yours showed a genuine love! And drawing your reader ( ME ) into your story and your family, I am left with a new fondness of for this joyful little bird singing his heart out. Thank you for your story!

You’ve made my week. I’ve recently moved after a lifetime in New Orleans, and there are no mockingbirds here. How I miss them, and the cicadas too. Thank you, Alene. If I may ask, where do you live?