… (cont’d from pg.3)

_______________________

.

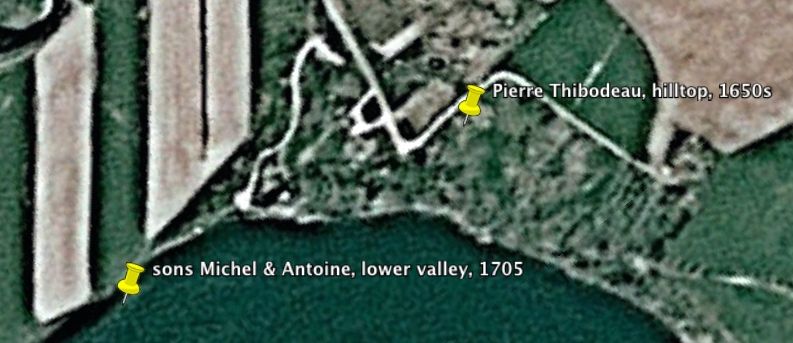

Round Hill, referred to on the census map as both Pre Ronde and Thibodeau Village, was about a half mile upriver from Port Royal, a peaceful scenic drive that kept company with the river from up in the foothills. From there, on the approach, I recognized immediately the distinctly long and skinny shape of the peninsula that jutted sharply into the river’s floodplain, a shape I knew so well from the old map. I also saw, on the far side of its narrow neck, the small hill, now covered in woods, that rose peculiarly from the middle of the floodplain. On the 1707 census map, it showed that Pierre Thibodeau had built his home on the top of that hill, and two of his grown sons who’d married in 1705 and 1706 were just down the inland slope from him. He and his wife Catherine, whom he married in 1660, raised 13 children there; 8 girls and 7 boys.

.

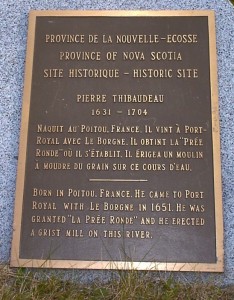

The modern village of Pre Ronde is in the foothills above the valley at a point on the highway where a bridge crossed a creek that I was told Thibodeau had built his grist mill on. To one side of the bridge, at the highway, was a Canadian flag marking a monument site where a millstone stood up in a hedge of ornamental junipers, and a bronze plaque that read:

My glee over the monument and mounting curiosity were not to last long, as I took the wrong road down to the river and then tried to reach the right one via a gravel path that I didn’t know had once been the bed for the railroad track that had long ago been pulled up. The bridge where the path crossed Thibodeau’s creek was where the nightmare of K-man’s Black Monday began.

.

One of the railroad ties collapsed under the weight of K’s front tires and fell into the creek below, pitching K forward onto his front fender and me into the steering wheel. Thinking the whole of the van would be following the broken beam any second, I immediately got out of the van and off of the bridge.

It took a long time crossing many fields before I came across a huge reaping machine that was ‘laying’ bales of hay like they were dinosaur eggs. The driver gave me a ride way up in his glass-enclosed, air-conditioned cab, slow as molasses, to the nearest person’s house where I could call a tow truck from, and it took a long time for the tow truck to get there. It took a long time for the tow-truck to make it down the other end of the road to get in front of me, and a long time to figure out that he couldn’t that he couldn’t lift me up out of the rut without an overhead winch or, after that, pull me out without my back tires then also falling down into the same rut. It took him a long time to figure out that he needed to back out, all the way back up to the highway, and come back the other way, behind me, to back me off the bridge.

But when it was finally done, and I was exhilarated at being clear of the bridge, it didn’t take me any time at all to reverse myself into too sharp a turn, too soon, and back K right into the ravine beside the bridge that sloped down into the creek. I wouldn’t know til the next day from the bruises how badly I’d been thrown first against the desk and then the bed in back, but I knew right off that the van was rocking on its axle right on the edge and that I had to get out of the van fast, again, but that this time it was going to be much harder to climb my way upwards and out of the driver’s window, which now opened out more onto sky than earth. The horror-struck look on the tow truck driver, looking at my face while the van rocked, is not something I will soon forget.

When I finally got my feet on solid ground again, our relief was soon replaced with the realization that the tow truck couldn’t get K out, and further, with every try, the agonizing rock back into place increased the likelihood that the van would slide down even further. So… it took a long time for him to go back to a phone and find the nearest town with a big flat bed tow truck, and then another long time for him to get there. After making the call, the first guy came back and kept me company, which I thought was really decent of him, waiting with me for over an hour and letting me smoke half his pack of cigarettes. First cigarettes I’d had in over a decade.

Mentally, I imagined putting all my things in boxes and shipping them to my grandmother’s house, or my best friend Susan’s, and flying home, leaving K in a dead car heap in some scrap yard somewhere in Halifax. But to my amazement, when K was finally pulled free, he started right up and drove out like nothing had happened. Even the computer equipment was fine, as it had all been against the right wall to begin with. Dumb luck.

Still, it was two days before I could move comfortably and several more before I could bring myself to go back to Pre Ronde.

.

__________________________

.

When I finally did, though, the old feeling was back; walking in the footsteps of ghosts of my grandmother’s people, stepping back in time. This road (the right one this time), this simple road that descended down the middle of the long peninsula; was it the same path that Thibodeau had forged through the wilderness that was the valley 350 years ago?.. that his horse and wagon took in and out of his fields, up into the woods to his mill? Is this the road he took to get up to the road that brought him to his friends and neighbors along the river, or into town? Would it lead me to his house?

.

Past the point where there weren’t any houses anymore, there was a remnant of a forgotten old wooden gate that looked like it had once extended across the road, with an apple tree growing up around it, and a thick-trunked hardwood standing behind that with a sign that read ‘Pheasant Preserve, No Hunting’. Okay!.. not your plain average pasture. It didn’t seem to lead to or from anything, and the seamless expanse of hay grass waving golden in the breeze behind it didn’t indicate any kind of property delineation. It was just in the middle of nowhere, the first of several curiosities that sent me driving K up and down the valley at least 20 times those first few days, just hoping to spot something that could put things like this little bit of wooden fencing in a broader context, maybe tell me something of Thibodeau Village’s more recent tenants across the centuries (like their being pheasant protectors). Unlike in Chipoudy, however, there were no resident historians to answer any of my questions about the old Thibodeau Village. The old couple with the store up where the path rejoined the highway were the only people I ever met from the area and they knew of no one who knew anything about Thibodeau except that his mill had been up the hill, and that it was his millstone next to the plaque.

Continuing down into the valley, the road began to rise again as it got nearer to Thibodeau’s hill, which was densely wooded at the top, but when it reached it, it turned off to the left, then the right, in clean 90 degree turns, as if to contain the woods to the right of the road from the open fields to the left. Just as well, I thought, cuz the woods were so densely clogged with impenetrable thorny brambles that I didn’t see how I would ever be able to see, or even get near, a cellar site, if there still was one.

.

.

Descending the far side of the hill, while open hay grass and corn fields continued uninterrupted to my left, the woods up on the hill thinned out, sloping down into an untended grassy pasture, lined at the far side by a wall of brambles that overlooked the water, and leveling out into another wooded area.

.

Past those trees, the road took a turn to the right, and again to the left, as cleanly as before, bringing it back to its original position and effectively carving out a small rectangle of abandoned overgrown greenery on the eastern edge of the valley, surrounded by a cultivated patchwork of wheat grass and corn fields that spread out across the rest of the valley down to the tip. At the very tip, I walked a stretch of raised levee that was probably too far out to be Thibodeau’s. It was only a small segment that rose significantly above the fields to be noticeable and seemed untended, allowed to go wild. But then the Annapolis Valley didn’t need dikes anymore, not since 1984 when they installed a new tidal power station downriver at Port Royal which kept the tides out. (That’s a story unto itself, one of only a few tidal power turbines in the world, and one on whose cost/benefit ratio the jury is still out.)

.

On the way back up, I noticed that the woods at the lower part of the hill weren’t as wild as up on the hill, and the trees adjoining the open pasture weren’t a tangle of hardwoods and brambles at all, but apple trees. On inspection, it turned out they were old apple trees, all gnarly and bent, their grid-like spacing barely perceptible through the undergrowth until you got out and walked among them. Only then did I see that it had obviously been an orchard, in a grid of maybe 8×10 trees.

I had been told something about the Annapolis Valley apples back at the Halifax museum, something about a genetic study someone had done on some old gnarled apple trees like this that could be found up and down the Annapolis Valley. The Acadians were known for their apple orchards, but the British who came after continued the tradition, no doubt bringing in their own favorite cultivars and turning the Annapolis Valley apple into the popular industry that it is today. So the geneticists compared them with modern apples from orchards elsewhere in the valley and modern apples from the Poitou region of France where most of the Acadians came from, and found several of the old trees had more genetically in common with the French trees than their neighbors from right around the next river bend. Could these be descendants of Thibodeau’s trees, brought here in those ships from the 1630s? Who knows what the tenants of this land after Thibodeau had done with his orchard or how many changes had been made to the pattern of land use since.

I knew that apples were propagated not by seed, but by grafting branches of favorite trees onto the trunks of others, enabling a farmer to prolong the life of his best trees many generations beyond its natural lifespan. Were these trees remnants of Thibodeau’s orchard? No way to tell. But if any of them were, it was most likely a much purer form of its original than 370 years would normally create. What I did know?.. there was nothing old and gnarly about the apples themselves… sweet and juicy to perfection. Ate one right there walking around.

.

Had another with a donair sandwich for lunch out in the pasture just uphill, on a massive wood beam slab, of relatively recent construction, the cover of a stone well that seemed way older, whose one visible ring of stones was encrusted with layers and layers of colorful mosses and lichens. That well cover saw many lunches throughout the summer, where I’d spread out a blanket and my laptop. I’d keep K right there in the middle of the road, not 50 ft away, blocking God and everyone, keys always at the ready. But in all the time I spent there, the only vehicles I ever saw that far down the valley were the big harvesters in the fields, and they told me they didn’t use the road.

As if I weren’t enchanted enough with the place, a stroll after lunch by the brambles along the east side, looking for a view of the water, yielded fistfuls of the fattest, most perfect blackberries I’d ever tasted. What’s with the fruit around here, and why doesn’t grocery store fruit taste like this? Blackberry gathering also became a regular thing for me, right along with visiting the apple orchard, until one day, early on in my explorations of Pre Ronde, when I was nearly plowed into by a flustering flurry of long gold and pink plumes. It was probably a male pheasant hitting me on purpose, endangering his own life to draw my attention away from a nest that must have been very near. Not to worry, Papa. I slowly backed away. Oh, I still collected my berries. But I never took another questionable step in those thickets, or anywhere else on the peninsula, but what the flat of my machete blade didn’t show me exactly what was under my feet before I stepped.

.

___________________________

.

It was from that blackberry hedge, looking up the hill, that I first saw the peak of a roof sticking up from the woods at the top of the hill. Excited beyond words, I packed up and raced back to the van, drove down to the nearest turnaround and then back up to the wooded hill to look for the driveway that I had obviously missed. I never found anything but a slight weed-filled clearing that at least got K off the road, but a bit farther, I did see a small modern house I hadn’t seen on the way down. On the upriver side of Pre Ronde, like the hill, it overlooked the east curve of the peninsula’s neck roughly in the direction of where the 1707 map said Thibodeau’s 2 boys’ homes would have been. To my disappointment, there was no one home to answer my knock, but the house backed onto a bluff that had been cleared of the ubiquitous berry brambles enough to afford a wide view of the east side, both the river and the wheat field below where the Thibodeau boys’ houses had once been, so I took the opportunity to take a panorama shot. It wasn’t until I got to the last shot on the left that I saw it, a white house at the top of the hill. Surely they would know if they’d ever seen anything that looked like a buried cellar site. The woods on the hill weren’t anything that looked old-growth, except one or two hardwoods; surely the hill had been clear recently enough for them to have had a decent view.

.

But no. The place was abandoned and falling apart. I couldn’t even see the front door for the wall of blackberry thorns. Circling the house meant hacking a path with my machete, watching for nests the whole way, which was okay for just today’s slender path, but as I hacked, I imagined a lawnmower, rented from wherever, clearing the ground enough to reveal a rectangle of stones or a sudden pit in the ground. In my head I went back and forth… Do I really want to disturb this many pheasant homes?… But it’s 350 years of history… But maybe rabbits, too. There’s no telling who all… But it’s for Omini (my grandmother)… yada-yada. I needn’t have worried, though, cuz my foot hit a scrapped water heater, and then an iron tub, then an array of pipes and gutters, and all manner of litter that covered nearly the whole yard, hidden by the blanket of grass. So there went the lawnmower idea. By the time I got to the back door, whose raised porch was collapsing around a small sink held in its place only by its pipe, I realized the scope of just how much of my dream of hunting for Thibodeau’s cellar site had also gone out the window with the lawnmower. When I finally hacked my way through to the clearing that sloped down to the well, which I could just barely see, I was too depressed to enjoy how lovely the view was.

The next day, I had a long talk with the store owners up the hill, who sympathized but had no answers, and whose attention to the map that showed where the 3 Thibodeau houses had been seemed more like kindly patience than anything else. Back down in the valley, I walked around, pacing here and there around the house, pondering just how I could find a way to feel around with my boots for a cellar site and be able to tell it apart from the other detritus that I had no intention of moving. It certainly involved tedious removal of brambles, anyway, and meant total disruption of what was surely the best critter habitat in the valley. After lunch, I set to clearing the little bit of path that remained around the house, which wasn’t as hard as the other side, through to the front door, which wasn’t as badly blocked from this side as it had been from the other, either. In fact, the plywood where the front door had been had started falling away so long ago that I could see right into the living room. Though the house seemed about 100 years old, it looked like it had been a relatively modern household, certainly within my lifetime, with papers and magazines strewn on the floor, left behind by the movers. I slid in easily, and looked for dates on the papers and magazines… all 1973. That’s about what my friends up at the store had told me the day before. All they knew was their name, no phone number, and that they’d moved to Halifax some 30 years before. When I asked the store owners what they thought I should do regarding asking someone’s permission to look around the property for signs of a cellar site, they scoffed and told me to go on ahead. So I did. I had no intention of disrupting anything but weeds.

Nice couple. That day, at the end of their day after closing up the shop, they drove all the way down to check to see that I was okay, and I made it a point from then on to check in with them in the morning whenever I was going to be there… and have a scoop of their lemon ice-box chiffon ice cream… and to check in with them when I left to save them from having to check on me again. They’d even said I could leave the store’s phone number for messages if I decided to look the owners up in Halifax, which I had planned on doing. Turns out I didn’t need it. Cuz when I was inside the house, taking a once-around, I saw steps that led to a cellar. The cellar of this house! Of course.

.

_____________________________

.

.

I saw that one side of the steps was all but loose from its mooring, and that it was pitch black inside, with not even a hint of a window. As badly as I wanted to go rushing down into my ancestors’ house, it wasn’t bad enough to fall inside with no way out. So after getting a few extra things from the ‘tool room’ of the van, under the bed, I set about finding an exterior way in. It wasn’t hard, being right where I figured it would be, at the back next to the collapsed porch I’d seen earlier. A cut had been made into the hill to allow for a full door’s height, and being lined with rocks, had not been overgrown with vegetation.

But what a doorway! I immediately understood why the house had been abandoned. It was listing sharply toward the back. The door frame, jammed into the ground and all twisted up like a trapezoid, said it all. And the heavy wooden door further back, pushed forward at the top, was jammed shut by the ground. The dirt beneath it was as hard-packed as stone, but it was dirt, thankfully. My trowel was painfully slow going, but hammering a screwdriver into the ground loosened things up considerably. The next day, after a sleepless night, I freed the base enough to fit my hips through, and I was in. In pitch black, despite the slight opening of the door. My lantern shone faintly across many pieces of random lumber jammed up into the ceiling at all angles, obviously an attempt to prop up the house, and in one corner, a knee-high makeshift retaining wall tried in vain to stem the bulge of stones in a caving cellar wall. There were things like an old lawnmower, and old sofa, a broken drafting table and whatnot against the walls, but not so much that you couldn’t see the whole wall in places from top to bottom and the five distinct construction periods obvious in the strata of these walls.

.

Something I should explain. I had read somewhere that you could tell an Acadian cellar from a British cellar of the same period by the mortar. The British used mortar between the stones, but the Acadians didn’t… didn’t have lime, filling in the spaces with smaller handcut stones instead. Perhaps I was wrong to do this, but one stone about the size of my palm that was obviously chiseled just so, and sitting unconnected and unneeded by the bigger crevasse it sat in, went in the big cavity under the driver’s seat, the section of K that had become the designated spot for a growing collection of such items from nature as stones, shells, little glass bottles of river water and gnarly apple branches.

.

.

.

.

.

That week’s letter to my grandmother was full of emotion about my love of the past that I don’t need to put here. It was full of my love for my grandmother that I’ve expressed sufficiently enough. And it was full of thanks for her generosity, breaking through the shame she felt of being Cajun… (for that’s what being a Cajun meant when she was growing up)… to finally tell me, after endless bullying, about her childhood, the culture of her childhood, the stories I wanted to hear, and the explanations of the photographs she had such a mountain of. It had always been, “Oh, you don’t want to hear about my ordinary life, I’d rather hear about you”, until I went to get a Master’s at USL in Lafayette. Cuz it was then that I saw the farm she was born on for the first time in my life, in Breaux Bridge on the Bayou Teche, and where her cousins still lived on adjoining properties. And it was then that I met the old-timers who took me all around and awakened my interest in my grandmother’s heritage.

.

.

________________________

There were many more sites to see that summer and reading materials to explore, and I stayed until autumn threatened to put me on the road in snow, fishtailing at 80 mph down the TransCanada. But nothing ever quite approached the sensation of that day.

.

.

.

.

.

.

* * * EPILOGUE * * *

At the time I made this trip, in 2000, I had not yet discovered Google Earth. But during the past month writing this story, I used the satellite’s view several times to double check my statements regarding locations. If only my grandmother were still alive to see what I found.

.

.

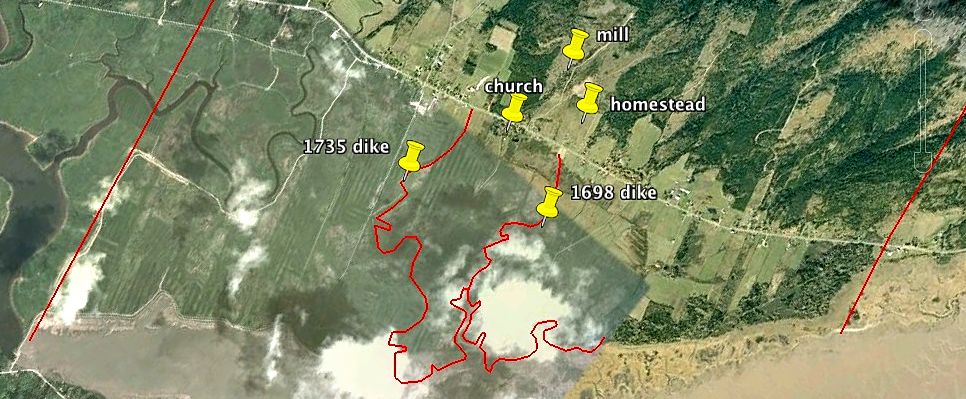

I’d long known that aerial photography could sometimes reveal from growth patterns in vegetation the locations of things underground. It was aerial photography that verified the deportation site at Grand Pre. But I didn’t go to Google Earth looking for hidden things underground, but rather to plot the mill and church sites at Chipoudy, both of which I knew and had visited, and the dikes, which I’d found more recently on a 1750 map of Thibodeau’s village. But like an optical illusion, where you stare at a picture for an hour and then a completely different picture jumps out at you, suddenly there it was, Thibodeau’s homestead. I must have driven K along this stretch between Hopewell Hills and Shepody 100 times, never knowing. You can’t tell from the road. But here in this shot, there they are.

The 1750 map showed a cluster of 4 little black squares right above the road, 2 near the road and 2 right behind them uphill, and identified them as the homes of Pierre’s youngest son Charles, then 61, and the families of his grown son Claude, niece Anastasie and nephew Michel. I’d been working with this map for so long that the specific off-kilter placement of those squares was etched in my brain. And it was that off-kilter positioning of the 4 squares in the satellite shot that jumped out at me. Not the squares of individual houses as I’d always assumed, but of huge patches of pasture, each the size of a modern city block. There, between the ‘homestead’ pushpin and the highway, pale green outlines against the darker grass. (C’mon, you gotta want it. Look at the white roofs of the present-day house and garage, and the driveway; they constitute the left side of the bottom left square.) I’d bet everything I own that the lines represent where the stone wall enclosures had been, and that the bottom row is still there, long ago lost beneath the surface, stunting the growth of the grass on top of it. I can picture the buzz of life within those walls, holding within their grassy expanse vegetable gardens, livestock pens and coops, barns for animals, tools, and crop storage, and all manner of specialized work areas pertaining to their boat, fur trapping, carpentry, etc. I’d also bet that the shadow on the top right homestead pinpoints the cellar site of the house, never completely filled in, the brush and trees inside the cavity thriving in the fertile gap between the wall stones, and never cleared because of the dip in the ground surface, or the rise of the house foundation stones, or both. I wouldn’t be surprised if the modern house stands on the site of the original, perhaps on a still-existing cellar.

I don’t know about you, but this sort of thing makes the hair on my arms go all fritzy. When I first found this and showed my husband, I had tears in my eyes. He’s a geologist and has an appreciation of history and time passage, and knew my grandmother before she died and knew what a magical thing she was and our relationship was.

.

.

Likewise in Port Royal at Pre Ronde. The image wasn’t clear enough to tell between the house on the hill and the woods around it, but the outline of his sons’ homesteads can be seen in the wheat field below, right where the 1707 map had them drawn, as well as hints of others in that valley that appear on the 1753 map just before the expulsion.

.

.

.

.

.

I would love to some day go back and walk the lines of these wonderful ghosts written into the land, but if I do, it won’t be in K. Goodbye, K-man, and thanks for the kick-ass memories.

.

.

.

.

.

.

______________ End of “Goodbye, K-man”, thanks for joining me. ______________

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Through you I visited a place I have wanted to see for many many years! Pierre was first of our ancestors to come from France and I have always wanted to see the first settlement. Thank you so much for sharing!

Delighted!, and thanks so much for telling me. Tell me about yourself and your connection to your Acadian roots. Are you in Louisiana?

Really enjoyed the blog. My paternal grandmother was a descendant of Pierre Thibodeau. In July 2013 my husband & I travelled from Ontario to visit Grand Pre & Poyal Royal. I was thrilled to find the plaque & the grist stone. We also drove down many if the rutted lanes trying to get a feel of the past. It was something I’ll always remember.

Thanks so much, Suzanne! Ontario – I guess that makes you a descendant of one of the lucky Thibodeau who escaped to Restigouche, but kept going, as opposed to mine who got captured there and sent back to the Halifax jail. I hope your drive down the rutted lanes was less exciting for your vehicle than it was mine;-)

Laura

Thanks for posting this. I am a descendant of Pierre Thibodeau as well. I am a fourth French Canadian and one eighth Acadian heritage. The rest is Irish. I have a travel journal a French Canadian ancestor in Maine wrote about her travels through Quebec with her sister my great grandmother. If anyone is interested it can be viewed here. https://notesdevoyagequebec.blogspot.com It’s important to erect monuments to our ancestors and preserve their memories. That plaque is nice. Things like Statues and Obelisks are a good idea to place in honor of our ancestors too. There is even cheap land people can buy out west for almost nothing, I bet some monuments could be built on that sort of land too.

I agree with you, Patrick. To know where one comes from grounds you. Canada is really good about marking sites like that, better than us. Their support of their provincial museums and such is wonderful. Where are you from and how did your family get there? Laura

How I wish I had met you 60 yrs. ago! I would have gone with you!

Being an artist, I am heading that way hoping to at least see the bronze plaque

of my ancestor grandfather, Pierre Thibodeau.

4/14/ 2020 Dear Laura, What a wonderful discovery I made today while studying my Pierre Thibodeau relatives that ended up in Trois Riveres and then on to Ashland, WI on Lake Superior. Your blog has made me so happy! I would like to take this trip someday in the future!

My maternal great grandfather Joseph Azarie Thibodeau (1858-1920) came to the US in the 1890’s. He became a citizen in 1906 and died in a tragic train accident while working on the iron ore docks in Ashland, WI.

Your pictures were wonderful! Thank you so much !

Oh, dear. A deadly train accident played a role in my background as well. I always wondered why my grandmother, at age 5, was suddenly moved with her family away from the family farm in Breaux Bridge around 1910 to Lake Charles, then an up-and-coming port near new oil finds in Texas. I think it was because her mother’s sister in Lake Charles was suddenly widowed with a young girl, also 5, when her husband was hit by a train that was supposed to have slowed to allow for work being done on the track of a bridge that he was overseeing, but didn’t. The two families lived together in the same house for 20 years, with no small amount of friction between them

That was quite the Nova Scotian adventure you had. Thank you for sharing your insight and experiences which fuels the imagination of what it must have been like and what they endured back then. My direct connection to Pierre was his daughter Jeanne who’s life took a somewhat different path.

Hi, Rick – How was Jeanne’s different? Did it relate directly to how your path differs from mine?

Laura

Hi, Rick. How was Jeanne’s path different? Does it relate directly to how your path being different from mine?

Wonderful tale. Pierre was also my husband’s 8th great grandfather. We still hope to visit Nova Scotia some day.