In July of 1987, I got on I-10 west with a suitcase, a camera and a notebook, and for the first time in my life after crossing the Atchafalaya Basin, took the Breaux Bridge exit south and descended into the Teche country, searching for my grandmother’s ancestors on a 19th cent. Cajun sugarcane farm. On the lonely highway that runs along the west side of the Teche, passing miles of sugarcane as far as the eye can see, I continued south into and back out of the town of Breaux Bridge until the cane fields resumed. Tisolay had given me the name of a cousin of hers who lived on the farm that shared the north boundary line of Tisolay’s family farm. I looked her up and she warmly shepherded me among various cousins who lived around her and on the opposite side of the bayou. They were all in their 70s and 80s, herself being the baby of the bunch in her spry late 60s, and though Tisolay’s grandparents, Adeo Hebert and Ada Babin, died about when or before they were born, they remembered Adeo’s house, his widow and his son. It was the warmest welcome by perfect strangers I had ever experienced. They laughed at me once when, half way from my car to their door, I ran back to lock the car, and from that moment the onion layers of my city-girl thinking began to fall away. I spent a couple weeks there, the first of many such visits to them, listening to their descriptions of where things were when there were still people living on the land, before the last of the family died off and the buildings slowly returned to nature. Already weakened by a 1922 flood that damaged the bousillage walls (a filling of mud and moss mashed between the wall beams), they were eventually dismantled for their valuable old-growth cypress, far preferable to new lumber, leaving only the pasture I saw before me. Sadly, I only missed seeing my gr.gr.grandfather Adeo’s house by 5 or 6 years. But I saw one of the things from Tisolay’s memories right away. Couldn’t have missed it.

It was the biggest pecan tree I had ever seen, looming over the corner where the highway met a dirt road that ran deep into the fields. Tisolay remembered being about 5 years old and playing by the tree, something about a tire swing. But other than the scrub trees that joined the pecan along the edges, there was nothing in the field but a swath of tall grass, a pretty red-tipped, wheat-like grass taller than my head, with the exception of two cedars jutting up purposefully and out of context from inside the sea of grass. The first time I stood on that corner with the pecan tree, where the road intersected a dirt tractor-access road at the south property line, I felt the hair on my arms creep up, a simple pasture though it may only have been.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

I was walking on my ancestors’ land, and it felt like they knew it and were watching me. “You don’t belong here; you aren’t one of us.” And it was true. Growing up in New Orleans, though its only 2 ½ hours away, is another world. There is no Cajun identity in New Orleans; we’re French Creole, very different in mindset. New Orleans was city life, sophisticated in the arts, educated, often in France, one of the richest cities in the country til the late 1800s, and whose worldliness still stems from one of the best ports in the western hemisphere. Cajuns in early-American Louisiana were almost as hesitant to send their kids to school as they had been in Nova Scotia because ‘the enemy’ ran the schools. Simple as that. Time did eventually bring political peace to Louisiana’s various ethnic groups, but when American statehood made formal schooling the law of the land, the urge to stamp out any part of the Cajun culture that hindered American assimilation remained. My grandmother remembers being punished for speaking French in school where reading and writing were only taught in English, and growing up with a shame of being Cajun that was consciously instilled for generations until only recently, when the nation’s discovery of Cajun cooking opened the doors for the anthropological paradigm of celebrating cultural differences finally began to hold sway. But Tisolay never attempted to instill any Cajun identity in me. She left Cajun country and married a fine Spanish New Orleans Creole and never looked back, and if the ancestors felt betrayed, well, I guess they had reason. So I figured I’d have to do the same with the ancestors as I had had to do with Tisolay when I first started asking her to tell me about her life … just wear them down til they gave up. It took alot to convince Tisolay that I thought the whole shame thing was hogwash and that not only would I not give her any peace until she’d taught me about this heritage of hers that I was so proud of, but until I’d taught her so much about the amazing history of her ancestors in Nova Scotia that she couldn’t help but be proud of them, too. Of course, then, my learning had only just begun. I didn’t know that 13 years of obsession and mountains of research later, I would make the sojourn up to Nova Scotia in one of the greatest adventures of my life, and be able to take her with me in the form of weekly letters and photos home when I found the stone cellar foundation of her 11-x-great grandfather’s mid-1600s house. But back then, standing under the pecan, imagining the ancestors scoffing, “what the hell does your punk-ass city self think you’re doing here!”, it was a good enough start simply to meet the ancestors with the same intransigence as I did Tisolay, and just keep returning.

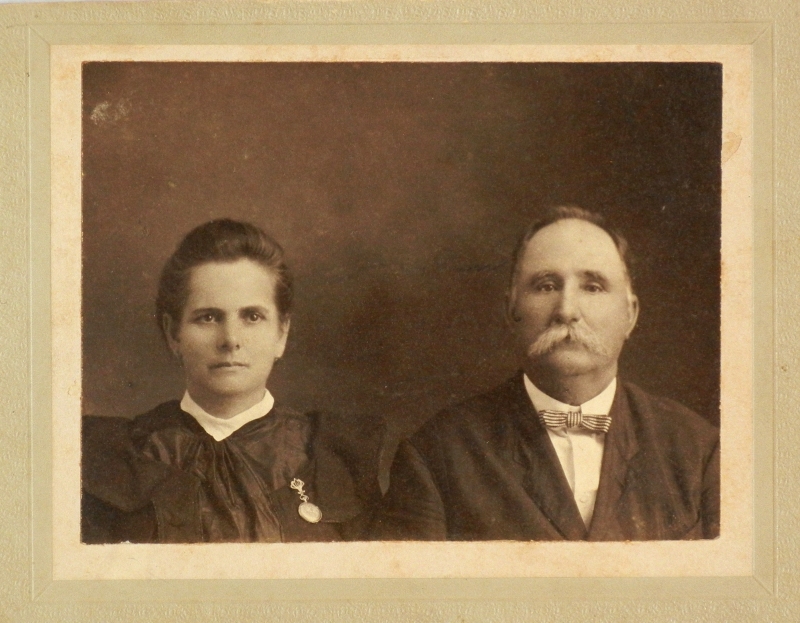

I actually had a really good vision of who they were, thanks to one of the flurry of projects I dragged Tisolay into after Granddaddy died in an effort to distract her from following him, which she was desperately willing herself to do. I’ve told you something of these projects, like cleaning out the attic, doing drawings, and cataloging the old Spanish documents from Granddaddy’ family. Well, we also tackled the uncatalogued mess of old photographs that had filled a bureau drawer in the library of Tisolay’s house to overflowing for as long as I could remember, which gave me a few faces to put to these ancestors breathing down my neck. Her grandparents, her mother’s parents, were Adeo Hebert and Ada Babin Hebert. Her grandmother, Ada Babin Hebert, died just before she was born, but she remembered her grandfather Adeo, ‘Yepope’ as she called him, and his second wife, Sidonie, a school teacher.

And thanks to the cousins, I knew that Adeo had built his house right here next to the pecan tree, up by the road. In fact, the two cedar trees in the sea of red grass had been planted by his second wife Sidonie, Tante Sin as everyone knew her, on either side of the front steps.

Looking down the dirt road that functioned as both tractor access road and southern property line, I saw that it extended easily a mile deep into the sugarcane fields before it hit a tree line, which reminded me of another of Tisolay’s memories, also from when she was 5. [All of her memories were from when she was 5. What happened when she was 5?] She would bound out of the back door with a slam of the screen door and run through the fields til she reached the railroad tracks at the back of the property where the train passed each day, very slowly so that the conductor could throw out the newspaper to every farm as it passed by.

What the hell, I thought, evaluating the summer’s heat, a pretty afternoon’s walk a mile down and a mile back won’t kill me. A minute or so down, the scrub trees that lined the property along the dirt road gave way to a clearing where a barbed-wire fence, just discernible within the brambles that clung to it, marked the end of the front square of red grasses where, I guessed, the various barns, sheds, animal pens and work areas associated with the house would have clustered around it. A clearing of about 25 ft wide separated the front square from the sugarcane, acres of graceful green rows swished in the breeze for as far back as I could see, beyond which, unseen, it sloped gradually down into the marsh until it pooled at the center as Lake Martin.

.

.

.

.

.

Neatly lined in front of where the rows of sugarcane started was a row of harvesters and tractors, trailers and wagons, modern and antique, all hip-deep in grass. Massive iron rested next to ancient cypress, with some asleep only since the previous season’s work, and some that had been asleep for decades and would never wake up again. Those, the real beauties, had rickety wooden sides that slanted outward, as sugarcane wagons do, and cypress boards that were rotting away from rusted hardware that could no longer hold them in place.

Across from the wagons, looking back toward the road, was a pile of heavy wooden beams tossed haphazardly on top of each other, and beyond that, a view of the cedar trees that marked where the front steps of Adeo and Ada’s house had been. In the weeks to come, I would ask the cousins enough questions about what the place had looked like that, one day, they took me into town to meet an elderly woman, the granddaughter of Adeo’s sister, Felonise. She had been taken in by the widowed Tante Sin and the never-married Adrien, both in their 60s, sometime in the 1920s when she was in her teens. She stayed with them through her marriage, bringing her husband to live with them and the laughter of a child back into the house when she had their daughter. And she stayed through the deaths of both Adrien and Tante Sin, and then finally her own husband, until the 1960s when she and her daughter, by then in her 30s and like her uncle “Po’Drien”, never married, left the deteriorating house to build a new brick home back on her father’s property in Breaux Bridge where she’d grown up.

.

As the last person to live in Adeo’s house, it was her photo album where I finally saw what Adeo’s house looked like. The earliest shot shows her husband milking a cow in the yard in back of the house with the help of his daughter, around 9, and another young boy.

From a few years later, maybe 1945, there were shots of the daughter on her Holy Confirmation with each of her parents, one with a view through the livingroom door and out the kitchen door in back. That shot also shows a porch swing which now hangs on the front porch of our cousin to the north, the one who sent Tisolay her pecans and took such wonderful care of me when I finally met her.

In 1948, she and her daughter, now around 37 & 16, were in a shot with Tante Sin standing outside what was probably a back bedroom. It was one of the last photos of Tante Sin before she died that same year. A part of the original house as it was when it was only a small, four room house, the house had since been greatly enlarged by a wing, just visible to the left in the photo, that went off the north side, and then back.

.

.

.

A shot from the 50’s or early 60s shows the daughter, a grown woman dressed for work, holding a small pet raccoon outside the back kitchen door where the cistern at the corner of the house and the pecan tree beyond can be seen.

.

.

.

.

.

Best of all, though, was one of the last shots taken before the aging house was abandoned to its decay, taken in 1964 of the house with its front porch nearly hidden behind Tante Sin’s 60 year old cedars and it’s white picket fence.

.

But standing there by that pile of railroad ties that day, looking back toward the road at the two cedars, the only view in my mind’s eye, somewhere in the sea of tall grass between me and those two trees, was of Tisolay bounding out of the kitchen door with the train whistle blowing in the distance. A slight shift in view from that pile of beams, though, sideways across the farm, revealed that the clearing was actually a corridor that cut not only through our farm but every one to the north and south of us for as far as I could see. And when I stood just so, in the very middle of the corridor, it was a view that explained the pile of beams; railroad ties pulled up from what could still clearly be seen in the irregular growth pattern of the grasses as where the tracks had once been.

They weren’t supposed to be there, though; they were supposed to be at the back of the property. Tisolay had been so clear about that, probably her most vivid memory of the farm as a child. Her telling of it always started with the slam of a screen door, and then running and running for miles through grass so tall that it swallowed her; a memory of excitement and expectation as she ran and ran, blindly through the ocean of grass, down to meet the train whose faraway whistle announced the slow-motion arrival of the newspaper to every farm along the Bayou Teche. The reward at the far end of this run was a marvel to her; the massive engine, the mechanical thunder, the churning wheel treadles, and the conductor who tossed the daily paper from right out of his window, often being met personally with a friendly word and a wave.

.

.

Let me say here that during those enchanted months of discovery after discovery, I pictured my grandmother standing right next to me a million times. Just as it had always been when we were together, so it was when I was away, with her as my invisible partner; me taking her with me everywhere in my mind, telling her things in my mind, and her, as always, frozen in time somewhere around the age of a typical grandmother.

But standing there looking back at the two cedars, not so very far away, I realized that the memory that Tisolay had told me countless times was that of a child who was still 5 years old. And that was when, for the first time and never once since, my Tisolay came and stood next to me as a 5 year old. It was like one of those scenes you see in movies, going back in time, me knowing who she was and wanting to hold her, but restraining myself, knowing that she didn’t know me.

It was a spot I returned to several times, most memorably after the snow of 1989.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Actually, I returned again and again over the next couple years, in all seasons and in all weather, sometimes at dawn, sometimes overnight in a tent with a nice bonfire, sometimes with friends, but mostly alone. I’d walk the land, exploring, and lay a blanket out under the sun down by the water near the old oak tree, usually with my notebook, a stack of xerox copies from my latest foray into the St Martinville notarial archives, maybe the latest publication from the Center for Louisiana Studies, often stopping in on one of the cousins to say hi. Just as I’d warned the ancestors I would.

The ancestors . . . I should introduce you to them. I’ll try to refrain from singing ♬ Cajun Cousins, sittin’ in a tree, ♫♪ k-i-s-s-i-n-g ♬

__________________

.

Was there any mention of salves (names) in the documenst you received.

Hi, Karen. No, slavery had been abolished about 30 years before the succession, and there was no mention of what the black and white families’ relationship had been before the war. I saw mention of Elizabeth and others a few times before the war, when they only had one name, in the successions of their white owners, Onezime’s parents and several aunts and uncles, who I’m fairly certain match up with their two-named counterpart listed in the first couple of censuses after the Civil War, 1870 & ’80.