For 35 years, I have been walking past this abandoned gem to get to my grandmother’s childhood farm which time, overgrowth and rust-frozen gates have rendered inaccessible any other way. It was falling down in ’87 when I first came to Cajun country for graduate school, and is only somewhat worse now. I wondered about the families who had lived, loved, fought, laughed and suffered in this enchanting little turn-of-the-century house, even imagined them as spirits visiting because they knew I was there thinking about them.

But back then, I only had eyes for the land that had been in my Cajun grandmother’s family since 1763 when her ancestors escaped to Louisiana after the British wrested control of the French colony of Acadia from France in the Seven Years War. They escaped the Grand Dérangement, the expulsion of the Acadians which saw fathers being forced onto separate ships from their wives and children, bound for separate ports on both sides of the Atlantic, in hopes of preventing them from ever reuniting in an effort to return. In the most remarkable reversal of a cultural diaspora I know of, Spain, who’d won Louisiana from France in the same war, invited the dispersed Acadian refugees, tried-and-true farmers who shared both Spain’s Catholicism and her hatred of all things British, to come settle southwest Louisiana’s rich bayou farmlands. And then they sent ships to the far shores to gather whoever wanted to go.

Two Thibodeaux cousins were given adjoining Spanish land grants along Bayou Teche, a tiny piece of which was now my grandmother’s, a sunny pasture where a few pieces of iron, concrete, and the occasional brick were all that was left of the 200+ years of our ancestors’ houses and barns and outbuildings that had once bustled with life for generations. Like the land next door, whose one remaining house seemed a only good burst of wind away from collapse, it sloped down to the bayou where floating water hyacinths bobbed beneath a row of gigantic moss-draped oaks, the southernmost of which shading the spot where I’d bring a blanket, my cat and my books to study.

It would be 3 decades before I learned whose house it had been on our unknown neighbor’s forgotten land.

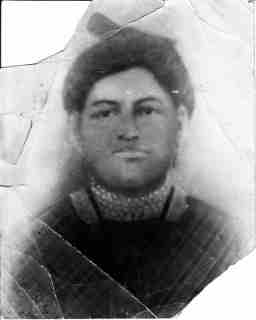

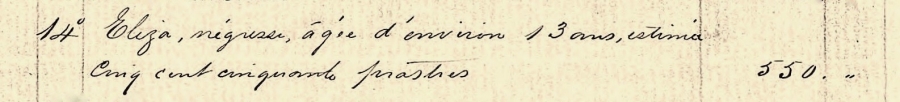

On Labor Day weekend of 2014, I first visited a Black Creole French family who had found me through the blog post I had written about my grandmother’s land, a family who grew up just the other side of the south fence, a family who turned out to be my 3rd cousins twice removed by way of my gr-gr-gr-grandmother’s brother, Onesime Thibodeaux, a white sugar cane farmer who raised 8 children over the 30-year period before, during and after the Civil War with one of his family’s slave women, Elizabeth Locus. His imminent death in 1893 caused his son Thelesphore to ride into town to get the priest to come to the house, quick, and marry his parents there by the old man’s deathbed before his children and their mother were evicted from their home. Thelesphore is considered the family hero by his descendants today, who are well aware of the remarkable 1894 succession and court battle that eventually secured the only home and livelihood Onesime’s children had ever known, as well as the heritage of their descendants who still live on Onesime’s land, land we were now having a cookout on. And it turns out, it was Thelesphore’s house that had been so picturesquely falling down for as long as I’d known it.

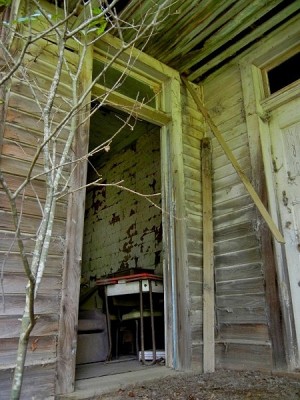

That Labor Day weekend in 2014, on the way back from a stroll to my family’s property, I had taken pictures of what I could see of the inside of the ‘little ghost house’, as I’d thought of it for years, from its doorways, most of which had long since lost their doors.

With more exterior weatherboards gone than there had been 30 years before, it was now apparent that there was no bousillage in the walls, an insulating mash of clay and moss squished between a framework of posts that was a signature feature of old Acadian homes like Thelesphore probably grew up in. There was also no lath and plaster. Rather, the interior walls were covered in wood planks as solidly as the exterior. The house was well built, nicely designed, and seemed more professionally conceived and executed than any of the houses on my gr-gr-grandfather’s property that had been described to me, something my few photos of his house verified.

Three doors opened out onto the front verandah, the middle one closed, but the ones at either side open to full view. The one at the far left, perpendicular to the others, opened into the parlor with its bay window. The closed middle door, aligned with the angled support joists for front steps that were no longer there, would have been the main entranceway.

The doorway at far right, halfway down the verandah, was unhinged and lay flat on the floor inside of what was probably a second bedroom that extended off the side of the house as a small wing.

A walk around back showed me that, much like the front, the back had 3 doors, 2 of them open, and not a set of steps between them.

In the crook of the “L” of the house, behind an old cistern that was leaning against the house, its foundation piers crumbling, was an open door that revealed a central vestibule which had doors on all 4 sides, one of them being the locked middle door I’d seen on the front verandah.

There was a bed’s box spring leaning against the wall, and a sliver’s view into the front parlor showed that there were several beds and mattresses there, too. The walls were wooden planks and still retained pieces of wallpapers in several layers, beneath which lay a base layer of old newspaper. No dates were visible, but I know I saw a headline with nazis in there somewhere. Abandoned and obviously ransacked, probably several times, what was left had been rejected into discarded heaps, broken or disintegrating, amidst dunes of accumulated leaves across the floor, blown in from everywhere. But the place nevertheless felt personal, speaking faintly of the people who had lived there… small people, from my perspective, because without stairs, the floor being almost up to my ribs, I saw things from the vantage point of a toddler. This is how Sylvia would have seen things when she visited her “Uncle Breaux”, what the kids inexplicably called Thelesphore.

My last glimpse into the house, though, through the door farthest to the back, was the one that magically suspended time for me. It opened into the last in a row of rooms that extended back from the front parlor toward the bayou, a very small room with a few shelves on a wall beside a window, and a large corner closet, like a pantry, with an array of white porcelain sauce pans, parts of an old drip coffee pot, and glass mason jars, one of which a bird had built its nest against. On the floor, there was a broken straight-back chair on its side, a broom nibbled down to the nub by somebody, and a pile of bricks that didn’t seem to belong.

It was the next-to-last room, though, half visible as well from where I stood, that did it for me. It had a brick fireplace, lit by a hint of daylight through a gaping hole in the floor where the hearthstone had fallen through, and a wooden mantle with a large glass jar still on it.

A wood-encased chimney soared up to a very high ceiling, from which hung a single bare light bulb on a brittle, cloth-wrapped wire. Sparse remnants of wallpaper peaked from behind a loose layer of dust-encrusted spiderwebs sagging in various stages of disintegration, sometimes suspended in thick ropes, that covered the bare wood walls. An old hand-wringer washer stood disjointedly near the doorway, and beyond it, on the floor in front of the hearth, sat a gallon can of Autocrat cooking oil, upright, as though someone who’d just been to the store had heard something awful, put the bag down right there where they stood, and run back out again.

By this time, I’d been away long enough from the carport cookout where the Thibodeaux clan, old and new, was spending a relaxing Labor Day around a steaming pot of Donald’s smothered chicken, and wanted to get back to the stories, so I waded my way through the scrub trees that nearly engulfed the house I’d been photographing, and rejoined everybody for stories that went on for the rest of the weekend.

~~ ☙❦❧ ~~

Nobody in the family could tell me anything about when Thelesphore’s house was built. All they knew was that family lore had the house being directly across the road from Onesime and Elizabeth’s, which put it within 50 ft from their neighbor to the north, my gr-gr-grandfather Adeo, Onesime’s nephew whom Onesime and his bachelor brothers had raised after the death of their oldest sister, Adeo’s mother. I recognized the design of the front porch columns and the brackets holding up the roof corners over the bay window as Queen Anne Eastlake, which became popular in the 1880s. But I knew that Onesime’s succession didn’t solidify Thelesphore’s ownership of the land until June of 1895. Would he build a house like this before he knew for sure that he owned the land? I wouldn’t think so, but he got married in 1890; where would he have brought his new bride to live? In 1890, his family home consisted of his parents, Onesime and Elizabeth, 67 and 47, sisters Thelisia and Felicia, 20 and 18, who were busy helping their mother, and Paul Hypolite, 15, working alongside Thelesphore in the fields. Children’s voices still rang through the house, with Clarisse, Louise and Charles being 11, 10 & 9, rounding out the family. Would there have been room for a newlywed couple? For that matter, Oneziphore, 2 years older than Thelesphore, got married 10 years before. Where did they go? Unfortunately, the 1890 census was destroyed in a fire in Washington D.C., but there’s no guarantee we’d have found anything out from it, as there seemed to be a reluctance on Onezime’s part to acknowledge the family that lived with him in the previous census of 1880 which, after some conspicuous and suspicious scratch-outs, listed him as the sole member of his household.

Turns out, though, some very interesting speculation arose as I poured through the censuses and listened to the family telling me of their memories from the 1940s. There was an 8-year gulf in age difference between the 2 oldest boys, born before the Civil War, and the 6 born after. Ironically, the Civil War years represented a home life of relative peace and quiet for Oneziphore and Thelesphore, but when they were 10 & 8, they were joined by a string of screaming babies and toddlers in the house every day for the next 14 years! At any point in the 2 boys’ later teen years, it seems reasonable that Onesime would have built, or allowed the boys to build, some kind of garconniere to alleviate crowding. And as they approached marriageable age, giving his sons a space of their own would have encouraged them to stay on the farm to raise their families and continue helping their father work the land.

It is possible that Oneziphore left the farm after he was married in 1880 to join his wife’s family, or else why was it Thelesphore, the second-oldest child, who eventually became the man of the house and executor of his father’s will. If there wasn’t a garconnière on the property yet, then-18-yr-old Thelesphore certainly had the motivation to build one after Oneziphore left, now being alone in a house full of little girls nowhere near his age. In addition to being his father’s sole farmhand, he was now the most likely target for any ill temper his father may have needed to get off his chest, a trait the current family remembers as common in their uncles and great-uncles, particularly toward the boys. And to top it off, Thelesphore didn’t get married until 10 years later. So it is more than reasonable to imagine Thelesphore building a garconnière for himself during his bachelor years, if there wasn’t one already, and managing the family farm as his father approached his 70s.

The family has vague memories from the 1940s of a ‘mud house’, they call it, very old, that had been directly behind the little Victorian house that Thelesphore eventually built, facing the back of the house as though it had once had a clear view of the road. It was very small & primitive, only two rooms and a fireplace. There were no windows, a single door at one end, and only a bare dirt floor. It was built with posts set directly into the ground rather than raised on the customary piers, preventing ventilation under the house as relief from the heat. The walls were made of bousillage, a plaster of clay and moss (hence “mud”) without the customary plank covering, or even a coat of paint against the elements, and heavy rains would have taken a toll on it, as well as the 1922 & ’27 floods. Nevertheless, it was a functioning home when the oldest members of the family knew it as children, albeit crumbling, lived in by their aunt and uncle, Thelesphore’s son Caffrey and his wife Anna until they moved into the big house around the mid 1940s.

There are no photos of the ‘mud house’, but I can show you what a bousillage house looks like from the inside, though the house in the photo was of more professional construction, was covered on the outside with weatherboards and painted on the inside, which the Thibodeaux house was not.

Was it so farfetched to think that the little structure could have been 50 years old when my Thibodeaux gang were children, predating the fine lovely Queen Anne-style home Thelesphore eventually built right in front of it? Could this have been the house he initially brought his young wife home to, back in 1890? Crude, it was, but perhaps it only needed to serve as an adjunct bedroom if they routinely spent a good part of their days, meal times and Sundays at the main family home?

~~ ☙❦❧ ~~

As I’ve told you, the 1890 census was destroyed in 1921 by a fire in Washington D.C. Interestingly, though, church records and court archives document the turbulence that marked the 1890s for Thelesphore and breathe life into events that may have affected his decision on when to build.

The decade started well enough, with his sisters Felicia, Thelisia, and himself all getting married within a 14 month period in 1889-90. Thelesphore married Marie Sidalise Filer in May of 1890. Not much is known about her, but the census from 1880, when she was a 13-yr-old girl, paints a poignant picture that is reminiscent of Thelesphore’s family story, being the child of a white man and one of the family slaves. Fifteen years after the Civil War had abolished slavery, Sidalise was 13 and living with her large 3-generation family of recently-freed slaves, her grandparents, the Fylers, being transplants from Virginia and Kentucky. They were living on lands owned by another large 3-generation family, the Gauthiers, a family of white, once-wealthy Louisiana planters. The Fylers, once slaves, were now listed in the census as employees on the plantation, the men as farm laborers, the grandmother as washerwoman, and Sidalise and her mother as domestic servants in the big house. Sidalise’s mother was listed as single, with a daughter, 13, and a son, 10, who each bore different last names, neither one Fyler, signifying different fathers. Everyone in Sidalise’s family was listed as Black except for Sidalise, who was designated Mulatto. And while her last name on her marriage document 10 years later with Thelesphore is Filer, the 1880 census shows the 13-yr-old girl’s name as Sidalise Gauthier.

Thelesphore and Sidalise had their first child, Cornelius, in April of 1893, and that’s when things started going bad for Thelesphore. Within 12 months of the child’s birth, Sidalise died, his father Onesime died, and he was thrust into a bitter court battle against his father’s sister who sued to nullify her brother’s deathbed marriage, and with it, his and his family’s rights to the only home, land, and livelihood they had ever known. As the new head of the family, embroiled in a fight for their father’s estate that apparently froze all finances, records show that Thelesphore not only paid the many costs of their father’s illness, death and burial, but also their maternal grandmother Clarisse Azor’s illness and death the following year. Judging from the list of estate debts that the court ordered the other 7 siblings to reimburse Thelesphore for, he had been paying all legal and court bills, as well as the estate’s routine bills for the family and the farm that had been previously his father’s responsibility.

With all his duties as head of the family during these stressful events, together with the dawn-to-dark routines of farming, one thing he could not do, apparently, was raise an infant alone. At some point, he relinquished the care of little Cornelius to the women in his family. As his two older married sisters had brought their husbands to make their homes there on the family property, the Thibodeaux farm probably took on the semblance of a communal family compound, and the 1900 census shows that by the time Cornelius was 7, he was living with his Aunt Thelisia and her family.

The 1900 census contains other telling nuances that hint at unusual circumstances. It is not unreasonable to guess that the care of Thelesphore’s infant son initially fell to his newly-widowed Grandmère Elizabeth in the old family home, which family lore suggests was directly across the road from Thelesphore’s house today. She would still have had the help of her last two unmarried daughters, Clarice and Louise being in their late teens and living at home, as well as her last 2 unmarried sons, Paul Hypolite and Charles.

We do know that after 17 months in court, the succession was settled in their favor, and perhaps it was at this point, in the summer of 1895, that Thelesphore felt financially stable enough to build his little Victorian house. We also know that another 17 months after that, time enough to design and build a house, Thelesphore got remarried in Nov. 1896 to Corinne Roy who would be the lady of the house (whichever house that was) for 43 years. Relevant to the age of the house, it would be reasonable to guess that Thelesphore built his house between the summer of 1895 and November of 1896. But relevant to little Cornelius, it would also have been reasonable to guess that 4 years after Thelesphore had married and there was again a woman in the house, the 1900 census would show that Thelesphore had brought his 7-yr-old son back home to live with him, which he did not. At first, this made me sad, wondering whether this was because of friction with his step-mother, or simply because he was hunkered in where he was. But if his childhood were anything like how Sylvia describes being raised 40 years later, Cornelius had many parents to raise him, embrace him, watch over and teach him, his father being one of them, with many houses to sleep in, many kitchens to eat in, many cousins to play with, and a big extended family group to grow up with, go to school with, go to church with, and gather for the big Sunday feast with.

Still, more sadness was to come for little Cornelius. Whether he originally went to live with his Grandmère or not, he would not have her for long. Just before turning 4, Elizabeth Locus died in March of 1897.

After 53 years of a difficult life that began in slavery, a woman whose life was not her own, who’d had no education, could neither read nor write, had borne children by two different men while still a slave, and for 25 years of living with Onesime and bearing his children, had not, nor had her children, been reported by Onesime in any census as being part of his household… Elizabeth Azor Locus Thibodeaux died a legally married woman, homeowner, and land owner.

Toward the end of her life, court records describe her as very shy, never leaving home, and fearful of speaking or being spoken to by others. But they also describe a home whose children had a devoted father they called ‘Didi’, and a couple whose relationship had been openly acknowledged and accepted by the community as a family unit for as far back as memory served. She died knowing that her children all owned their own homes and a family farm to support them. And she got to see her oldest 4 children married and have most of her 20 grandchildren growing up within sight of her house, the heart of the family compound.

Five years after her death, though, the 1900 census hints that her grandson Cornelius may have lost not only his grandmère, but the house as well. With both Onesime and Elizabeth gone, the old house Onesime had built as a young man in the 1850s seems to have been abandoned. By 1900, Elizabeth’s 4 unmarried children had all left the old house and moved in with their older siblings. Paul Hypolite, now listed as 25 and a farm laborer, had moved in with Thelesphore, Corinne, and their 2 small children. And Clarisse, 23, Louise, 20, and Charles, 19, had moved in with big sister Thelisia and her family. Whether Cornelius came with them from Elizabeth’s house, or he’d been at Thelisia’s all along, he was with them all at Thelisia’s in 1900.

The census of 1900 represents a relevant milestone, listing Onesime and Elizabeth’s children as homeowners and landed farmers, which very few former slaves were. In fact, it was the first time their children were listed at all. It is tempting to reflect on Onesime’s apparent reluctance to ever acknowledge on the census that he had a family, especially in light of the fact that the 1880 census taker had initially listed Isabelle (short for Elizabeth), her brother Antoine and her mother Clarice as living with Onesime. But he then put a line through their names and listed Onesime as a single man living alone. There are potential residents listed earlier on the page that could be them, allowing for some variation in age, indicating that the crossing out was simply to avoid repetition. But none of the 8 children are listed in any house nearby, or anywhere on the entire census (ask me how I know.) The previous decade, he listed other former slaves in Elizabeth’s extended family living with him readily enough, while Elizabeth (as Isabelle) and Thelesphore are living with her mother Clarice elsewhere on Onesime’s property. The 1870 and 1880 censuses after the Civil War, the first to include the black population, is rife with inaccuracies and confusions that reflect the upheaval surrounding their own need to choose a second name as a family name when they’d only ever had just the single name, as well as the white population’s reluctance to officially acknowledge relationships with former slaves that, nevermind going against certain social mores, were illegal well into the 20th century. Personally, I think it is worthy of note that Onesime, still unmarried in his late 30s by the time he had his first child with the slave woman Elizabeth, stayed with her exclusively for the rest of his life, bringing her into his home and raising their 8 children openly as their father.

The 1900 census was also the last to record all 8 children. The first decade of the 1900s was marked by the marriages of the youngest 4 of Thelesphore’s siblings, but also the deaths of 3 of the 4 older ones, save himself, and the start of the next generation’s emigration to east Texas. Felicia died in Dec.1901 at the young age of 31, leaving her husband with 7 children under 10. Paul Hypolite got married 4 months later, Clarisse a year after that, and three years later, in November of 1905, Louise married her sister Felicia’s widower of two years.

One month after Louise’s marriage, Thelisia, who had seen all of her younger siblings safely to adulthood after their mother’s death, died at age 33, leaving her husband with 9 children. He soon took their children to live with his family elsewhere in St Martin Parish, leaving Cornelius, nearly grown at 17, who finally went to live with his father, together with Corinne and their 6 children in their little Victorian house.

Whether that was the house he’d been born in back in 1893, before Onesime’s death, is doubtful, but where he was born, and when the little Victorian house was built is unknown. And the ‘mud’ house of distant memory, was that where Thelesphore spent his first married years with Sidalise?.. where his first son was born?.. where his young wife died?

Some mysteries are destined to remain such.

~~ ☙❦❧ ~~

As usual, thank you for joining me in my search through time.