(cont’d from previous post)

It’s been months since I discovered the McNeese Collection of vintage photos of Lake Charles, but they still flood me with feelings of closeness to Tisolay, my grandmother, especially those taken of places and events in the same year she’d have seen them, letting me see what she saw through her eyes as a girl. It’s as though it were a gift from the universe, a moment when her eyes as a teenager then and my eyes now meet and we become conscious of each other and can visit, even take a walk together through the streets as they are today with the help of Google Earth’s street view to these places that could have been very meaningful to her in her young years. And she can tell me about the places in the old photos as they were in her time, when she knew and loved them. In those rare times when I can find an old photo of something that still exists, and Google Earth gives me the same view, the time merge knocks my socks off. When it’s of a place I already know was meaningful to her, and I know the role it played for her, it can bring me to tears.

When I put 2 and 2 together about my great aunt Beulah’s class ring, (see Leaving Cajun Country…) marked ‘1908, Lake Charles High School’, it disproved much of what Tisolay had always believed about when and why her family had left Cajun Country for Lake Charles. This pushed something of a reset button for me, but gave me a solid starting point in time from which to start over. For Beulah to have graduated in 1908, the family couldn’t have gotten to Lake Charles any later than January of ’08, and probably moved the summer before, in ’07, much earlier than Tisolay had thought, though being 2 or 3, she had no memory of it herself. I can imagine J Euclide and Tiwazzo, my grandmother’s parents, and the kids, spending their last Christmas on the farm on Bayou Teche, amidst the swishing sugar cane fields, their last Christmas with Yépope, as the kids called their grandpère Adeo, and his new wife Sidonie whom everyone called Tante Sin, and Nonc Adrien, Tiwazzo’s brother. By waiting til the middle of the school year, they’d still be there in November to help with the sugar cane harvest. I wonder, though, if Tiwazzo saw continuity in her children’s school year as a factor worthy of consideration, and rather than disrupt everyone’s school year, preferred to move in the summer before, in 1907. Considering Tiwazzo was from a rural farming community where school routinely took 2nd place to both the springtime planting and autumn harvest seasons, and financial constraints often required teenagers to quit school to work, it says something about her that all 5 of her children completed high school.

In any case, when the Champagne family stepped off the train in Lake Charles, be it in the summer of ’07 or the following winter, Beulah would have been 16 and entering Lake Charles High School’s senior class, knowing that she was on the cusp of going out into the world to find a job to help support the family, and meeting young men, one of whom would be her future husband. Carmen would have been 13, joining the freshman class, maybe just starting to be interested in boys, but probably not yet. Both girls were probably missing friends. Presley and Roosevelt, at 10 and 9, going into 6th and 5th grades, might not have formed bonds with friends as closely as the girls, but who knows. Were they resentful and reluctant to explore their new town, any of them? Were they eager and curious to know what town life was like? Little Stella (my grandmother Tisolay), being 2½ or 3, would have been a happy toddler, all eyes, unconcerned with changes. She wouldn’t be starting school for another couple years.

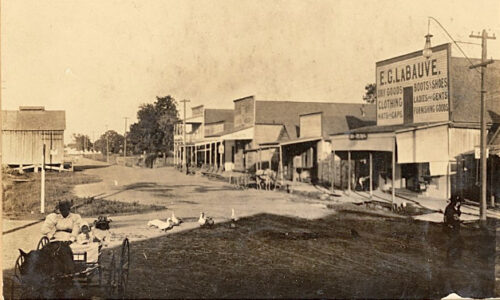

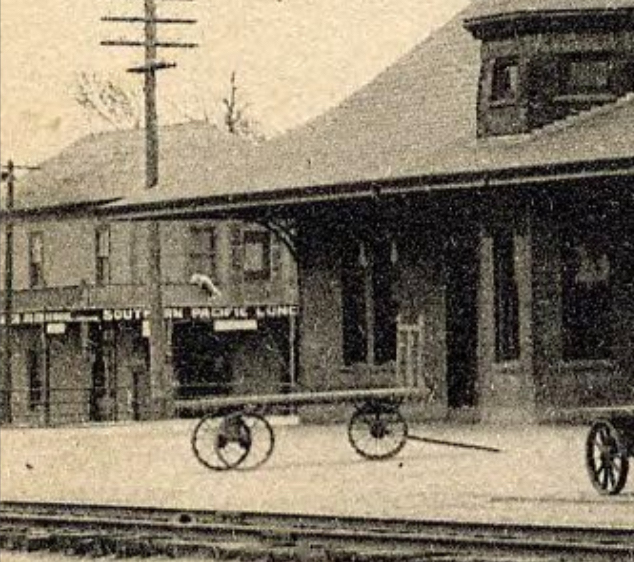

What would the first thing be that they saw of Lake Charles? Well, “comin’ right out the gate” as it were, almost the minute I found the McNeese Collection, I found a shot of exactly that, the first thing they would have seen, from the vantage point they would have seen it from, the same year they would have seen it . . . the Southern Pacific passenger depot, from inside the train, pulling in from the east, taken in 1907.

It floors me still.

~~~~~ the depot & Railroad Ave. ~~~~~

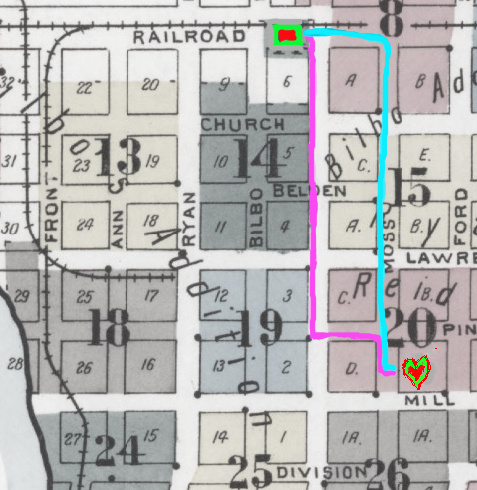

🎶My God, Tisolay, look at this. For all we know, Uncle Michel is one of those men, waiting for your train to arrive, making arrangements with a drayman to manage y’all’s luggage and take everyone to your new home. “511 Moss St, please.” And it would’ve been a short trip, too, just 4 or 5 blocks south.🎶

The depot’s gone, unfortunately, destroyed in a fire in the late 1980s, and its lovely turrets were taken by a hurricane long before then. Everything else around it, too, is gone, abandoned, the only remains of the businesses that catered to train travelers being the old concrete slabs, crumbling and shot through with weed-filled crevasses. A few of them still bear remnants of the walls they once supported, or did until the 2020 hurricanes.

A photographic moment in honor of the many people whose lives will never be the same, a city that isn’t getting enough help to recover, and a government that can’t possibly fund the barrage of disaster recoveries arising of global warming.

You would never know that even before the concrete, beneath the concrete, there’d once been a thriving little wooden community of boardinghouses, restaurants and storefronts catering to travelers up and down the road along the tracks… bakeries, barbers, drug stores and dry goods stores for those who’d left some necessity behind, groceries and meat markets for the restaurants and residents who worked in these stores and businesses. And of course, the saloons, billiards halls, and ‘red-light’ establishments, especially toward the far east end. In the 20s, my grandmother glided comfortably in and out of the station going to and from college in New Orleans. Whether she noticed that the little storefronts she passed as her train headed east out of the station, as well as the occasional scantily-clad woman, seemed to exist on a more licentious plane, I can’t say. Whether my great-grandparents J Euclide and Alicia (Tiwazzo) Champagne, 20 years earlier, knew why Railroad Ave was sometimes called by another, less official name, Battle Row, I can’t say either. But the drayman carrying the family and their luggage to their new home surely would have. Which street did he take? What were the first houses and people and little glimpses of life in Lake Charles did my little 2-yr-old grandmother see?

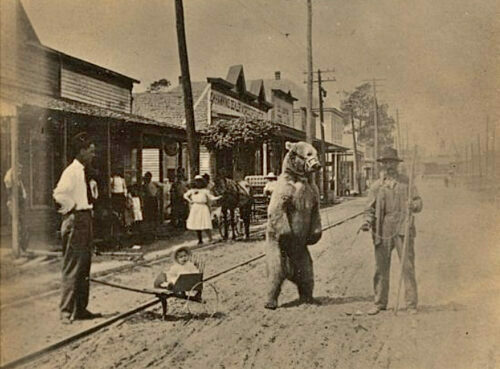

Two photos I’ve found through McNeese exemplify the two distinct personalities of Railroad Ave in those days when the Champagnes first saw it in 1907.

While it seems as though nothing remains of the depot, this is not exactly so.

A close-up of the above photos shows a 2-storey building with an upstairs balcony looking out over the far corner of Hodges and Railroad Ave. You can just make out the name of John Isaac’s restaurant, the Southern Pacific Lunch something, (the depot hides the rest of the name). The depot seems to sit at a level higher than the street, and you can just make out the faint lines of an iron railing, partly obscured by a luggage wagon, protecting those inside the depot grounds from the drop-off. Today, if you walk to the corner where the restaurant was, then turn back toward the depot site, you see a set of concrete stairs set into a crumbling retaining wall that tapers upward, once leading to a loading dock, the wall that held the iron railing at the southeast corner of the depot’s perimeter.

I can’t help but chuckle at the thought of the drayman deciding whether to avoid Railroad Ave entirely and take the newcomers down Hodges St straight from the depot, then switch over to Moss St a few blocks later, or to take Railroad Ave for a block to Moss St, then have a straight, 4-block shot to their house. He might have friends he could wave to, but there were 5 children in his carriage, after all. And maybe his friends were a good reason not to go down Railroad Ave.😉

If the driver decided to take Moss by way of Railroad Ave for a block, he’d have passed the Southern Pacific Lunch ‘something’ on his right, a bakery, and several groceries, before turning right (south) onto a block of shanties and small homes of laborers associated with the depot and the businesses around it.

~~~~~ Parsonage of the German Lutheran church ~~~~~

At the first intersection, Church St, when it started to feel like a neighborhood, one of the first things the Champagnes would have seen was a cemetery. From dancing bears and half-dressed women in the street to a cemetery; nothing Kafka-esque about that. 🤣

It was a quiet residential neighborhood, though, of wooden cottages with deep-shaded front porches. The older ones, typical of the earliest settlers, were simple, built without any particular architectural design in mind except protection from the heat… being raised off the ground for ventilation and having a deep porch for outdoor shade. The later ones were built after the railroad broke through the forbidding forest and swamp, bringing with it the popular Eastlake Victorian style of architecture.

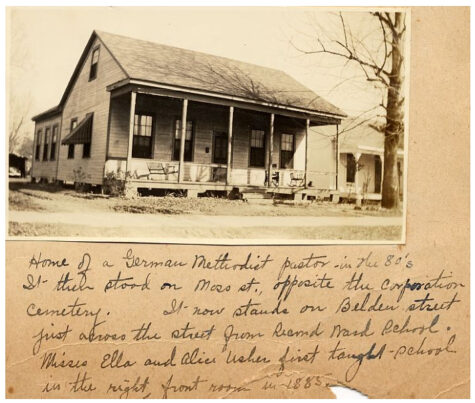

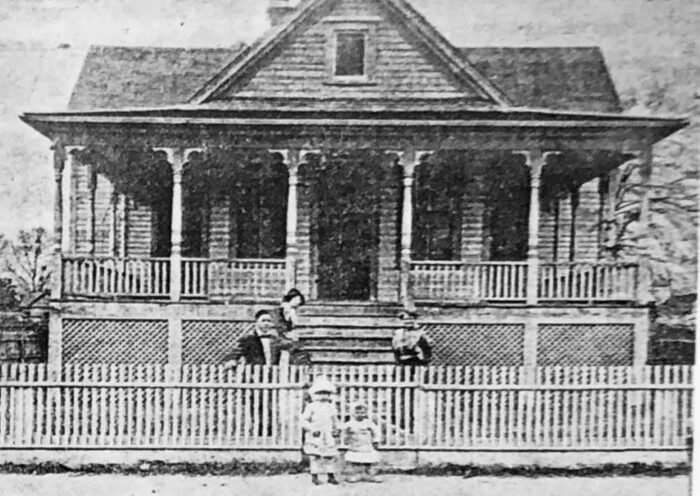

One of the earlier ones, built around 1875, was the home of the Methodist pastor, across from the cemetery. The Champagnes would see the house a block or so further along their ride, but it had originally been next to the little wood frame church that the Champagnes saw on their left as their carriage took them into the 2nd block south of the depot. It was typical of the early homes built before the railroad, the Victorian style, and big money found Lake Charles.

The old German Parsonage photo is one of the lucky ones in the McNeese archives to have been collected and captioned by Maude Reid, an avid Lake Charles historian born in 1882. She put her collection together in a series of scrapbooks, a staggering body of work, and donated them to McNeese. In fact over the course of decades, she captioned several copies of this photo. She tells the story more succinctly than I can.

“The old parsonage of the German Methodist church [before it was called Lutheran] on Moss Street where, in the front room on the right, I was taught my A.B.C.s by Ella and Alice Usher in the late 80’s. It was built in 1875 for the first German pastor, Rev. S. Hoernicke and stood next to the church on Moss street, just across the way from the old cemetery. . . . Back in the 80’s and 90’s there was one section of Lake Charles known as German Town. Not only because the First German Church and parsonage were in this section, but many German families lived there. Here lived the Bendixens, the Hansens, Cordsens, Jessens, Jacobsens, Mathis and others. The area designated as German Town comprised that section from Church street to Ford [then named German St], to Division, to Hodges street north to Church street. . . . When the new church was built on Ford street [in 1889), the old church was made into a residence, later occupied by the Abrego family. . . . The house was later moved and now stands on Belden street, across from 2nd Ward School.” – Maude Reid

No, Miss Maude, not anymore.

🎶 Tisolay, you must have known Maude Reid. She was a nurse in the Calcasieu parish public school system all through your years; would’ve been in her thirties when you started school. Plus she lived right behind you; never married, never left the family home.

If nothing else, you’d have seen her visiting her whole cluster of Reid and Hutchins cousins who lived all around you, several with children your age. You’d have known who her dad was, too, Sheriff DJ Reid, Jr. You probably would have heard of his dad, too, though he’d been gone for 25 years, a powerful judge from Lake Charles’ pioneer days whose ‘colorful’ character and hot temper were often spoken of in tandem with his Scottish heritage. Reid Jr, the judge’s son, built this house around 1900, moving in by 1901. The verandahs got blown off by the 1918 hurricane and were replaced without the nice denticulates, but otherwise it looks the same today.

I know Mother drove you through the neighborhood sometime after Granddaddy died, I think it was on the way back from the Hurricane Andrew evacuation in 1992. So I know you’ve seen what these wonderful oaks have done for the neighborhood in the century since you first knew it as a bare, wide open space, little saplings planted everywhere, and maybe the occasional big tree. 🎶

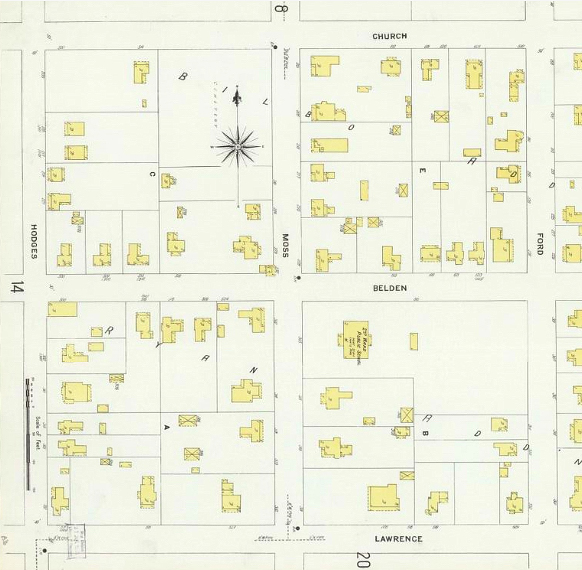

Miss Maude’s coordinates for German town, 2 blocks wide, 6 blocks long, running south from the railroad, overlap a good bit with the homestead of Judge David J Reid, Miss Maude’s grandfather. Not yet a judge, Reid was still the sheriff of the largely unpopulated wilderness that was Calcasieu Parish, elected in 1850 after he first came to the little outpost that was then referred to only as Charley’s Lake. He’d been a builder too, was friends with the original settler, Charles Sallier, and built his son Joe Charles’ house. But he was accumulating land and building investment properties for himself as well, investing in the growth of the little prairie outpost, before Daniel Goos, the Danish schooner captain who’d been carrying other people’s lumber to markets along the Gulf Coast, realized what a lumber ‘goldmine’ Lake Charles’ pine forests represented. Anyway, Reid donated a piece of his land, a block south of Railroad Ave, for a cemetery in 1857 when the town was first incorporated as Charlestown, the Corporation Cemetery they called it then. Fifteen years later, Goos returned from a trip to his homeland, Foehr, in the North Frisian Islands (by then wrested from Denmark by the Germans and reeling from the effects of war) with 3 ocean schooners full of experienced engineers and carpenters to work in his lumber mill, as well as shipbuilders, sea captains and sailors to transport his lumber to markets up and down the Gulf Coast. That’s when Goos founded the German Methodist Church for his newly-arrived countrymen right across from the town cemetery, and that’s where those newcomers started buying lots from Reid, slowly pushing the forest’s edge east, farther from the little town center… 3 blocks from the shoreline, then 4., etc.

~~~~~ the Hansens and the Cordsens ~~~~~

The very first intersection the Champagnes’ carriage came to, across from the cemetery, told the story of the Hansens and the Jacobsens, Foehr Islanders both, and a sea captain named Friedrichs Cordsen from the port town of Kappeln on the Baltic Sea, about 45 miles east of the Foehr Islands. And something of a sad story it was, though early deaths and dire straights seemed to always be a single week’s wages away for so many. Jocina Jacobsen left her homeland in the North Sea for America when she was 20, arriving with her family in one of Goos’ ships in Dec 1871 after a month at sea. Her brother Simon, a schooner captain who married Daniel Goos’ niece Gardina, lived a block further down Moss St. Jocina married fellow Foehr Islander Jacob Hansen, another of Goos’ schooner captains, in Sept of 1872 in New Orleans, eventually coming to Lake Charles and settling on Church St around the corner from the church on Moss. They had 3 children in their 11 years together, Ferdinand, John and Minnie, before Hansen was killed aboard his schooner, the Lydia, on the Calcasieu River in Nov. 1883. He was 36, his widow 32, young Fred and John 10 and 7, and little Minnie was 5.

Unexplained circumstances surround how and when Jocina met and married her 2nd husband, Captain Friedrichs Cordsen, in Galveston only 11 months after the death of Captain Hansen. He’d arrived from Germany 5 years before, sailing for Goos out of Galveston, and was 5 years Jocina’s junior. The young widow could have gone there with an eye toward selling Hansen’s ship, the Lydia, as was mentioned in her husband’s succession papers. Goos’ captains and his ships operated between Lake Charles and Galveston, and the Lydia was kept in Galveston much of the time. But her daughter with Cordsen, Marie, was born 6 months after their marriage, so going to Galveston could have been partly to keep the pregnancy hidden until she could return home with an explanation for the child. Her father was a steward on the Hamburg-America shipline and away at sea a lot, so her mother lived with Jocina on Church St and could have taken care of the children while their mother was gone. Adding to the mystery is the mention in her 1st husband’s succession papers that she had not followed legal protocol as responsible party for the children, all of whom were still minors, by clearing the marriage with the children’s legal family representatives. She lost her rights as natural tutrix to her children until her new husband was cleared as co-tutor, which he was.

Things seem to have evened out, though, and the Cordsens settled into a house somewhere near the corner between the Hansen home on Church St , then occupied by Jocina’s parents, and the church on Moss St. Somewhere along the line, during the Hansen marriage, they had acquired an old store building catercorner to the old parsonage that now served as housing for blue collar laborers, mostly African American. And then after the church was decommissioned in 1889, the Cordsens bought several more rental properties, one of them being the old parsonage.

In 1892, 8 years into their marriage, the town newspaper wrote of the 50th wedding anniversary celebration of Jocina’s parents Jans Lorenz Jacobsen and his wife Marie, which the entire German community took part in. The paper noted that, though it started soberly enough with a benediction in the new St John’s church, named after the church in Wyk on Foehr Island, “all present enjoyed themselves as only the Germans can, and the company dispersed at midnight.” In early 1896, though, the family was hit with a double whammy that was surely felt at Jocina’s middle son John’s wedding celebration later that year. Jans Jacobsen, age 76, died on Jan.29, and his son Simon, 52, died the following month at sea. Simon had been named after Jans’ big brother who’d been killed at the age of 25, the year before he was born, shot while hunting seals near Greenland . . . (this seafaring business is not for the faint-hearted!) Then, 3 years later . . . “Mrs [Jocina Jacobsen] Cordsen had been ill for only two days. The direct cause of death was heart failure, but the remote cause is thought to be an overdose of medicine taken for headache. Her husband, who was on his schooner, was caught by a telegram at Sabine Pass and summoned to her bedside.” American Press, March 1899

But then, the 1900 census shows us that he was remarried by August, living with his new wife Annie, his daughter Marie Phelonise(15), his step-daughter Minnie(21), and his former mother-in-law Marie Jacobsen(81). And her succession shows us an expenditure against the estate by her husband for a $2 bottle of Mumm’s champagne at the Cagney Christman’s saloon, bought . . . wait for it . . . the night after she died. Makes you wonder if there could have been a reason for Jocina’s unhappiness, if indeed it was unhappiness. But then, who knows. Would Jocina’s mother and daughter both have stayed with the Captain years into his 2nd marriage if they’d thought he’d done something untoward? Would John have named his second son after his step-father 3 years after his mother’s death?

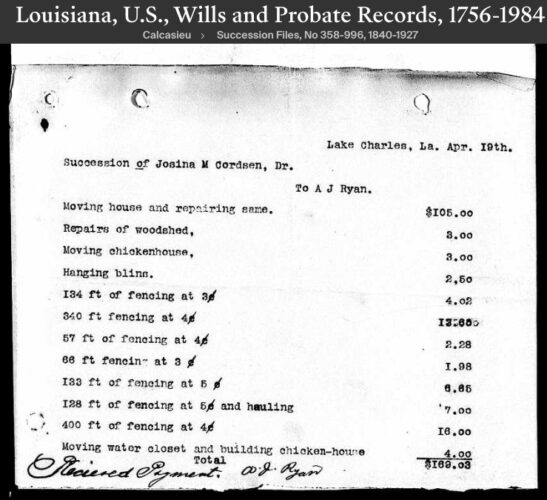

Not all the information in Jocina’s succession was unpleasant, either. Jocina had a piano valued at $100 and paid for piano lessons for her kids (the cost was torn off), as well as a yearly tuning by K. MacIver for $8 (we’ll be meeting him again in the next post). Her household and kitchen furnishings were valued at $200, the value of the lot with the Hansen house on it was $600, and the empty lot that eventually had the Cordsen house went for $300. Jocina was a businesswoman, though, keeping track of rental properties and repairs, tenants and rents, ordering lumber, hiring contractors, recording expenditures, etc., and many construction-related contracts were still open at the time of her death which means their final invoices and payment are recorded as part of the succession. The most interesting to me was the one hiring A J Ryan to move a house.

Was it the parsonage? I would assume so if it weren’t for the fact that the succession describes the lot where the Cordsen house is now (yes, it’s still there, a bit changed but recognizable) as being an empty lot, valued at half the price of the neighboring lot marked as having the “old house” on it. Was it the Cordsen house? Which one was the “old house”? Where was the Cordsen house moved from? What evidence there is is contradictory, which intrigued me. In this case though, unlike most, chasing down an online archival rabbit hole didn’t solve the mystery. Can’t win ’em all.

When the Champagne family arrived in 1907, it had been 35 years since Daniel Goos had sailed back from his homeland with shiploads full of hard-working Foehr Islanders. The community was in its 2nd and 3rd generations which had spread out as the boundaries of the growing town had spread. And by the time the Champagnes‘ carriage passed the wide corner lot that had held the 1870s parsonage, it had indeed been moved a block further down Moss and around the corner to become 619 Belden, across from the school as Miss Maude said. In its place were two houses, the second one, tight up against the old church, was still the home of Fred Cordsen, now 51, who still captained schooners, though no longer for the long-deceased Daniel Goos, and not so frequently since the railroad took over so much of the transport trade.

With Jocina Hansen Cordsen resting in peace for the past 8 years, he now lived with his 2nd wife Annie, 38, and their 3-yr-old baby girl Elsie, and likely spent much more time with his second daughter than he did his first. Whether built there new, onsite, or moved there from elsewhere, the Cordsen house was built in the old-fashioned, prairie style like the parsonage, but with a bay window to represent the Victorian influence that trickled in after the railroad was completed. Its front porch columns probably had 2 simple, somewhat-decorative brackets up at the roof. Coming from Galveston, which was connected to Houston by the railroad, Cordsen would have seen the Eastlake style there before he came to Lake Charles.

Today, though its deep shady front verandah has been closed in for interior space, you can still see the original eave at the roof where the overhang had been. I’ve been seeing that a lot in Lake Charles, where the bones of an old prairie-style home still exist, and wonder if this isn’t a by-product of mid-20th-century air conditioning, which eliminated the need to go outside to catch a breeze, as well as the frequency with which the windows and doors could be left open. Sadly, the time-honored culture of porch-socializing with the neighborhood went ‘out the window’, but, man, do I hate south Louisiana’s humid heat.

~~~~~ the Abregos ~~~~~

Passing the Cordsens, the Champagnes might have regarded the next house somewhat quizzically, wondering why the little house had its own bell tower. Eighteen years before, the little church had been outgrown by its Foehr Island community, and in 1889, it was replaced by St John’s Lutheran Church a few blocks down on German St, soon to be renamed Ford St, the next street over from Moss. As Maude Reid has told us, the church was decommissioned as a church and sold as a residence, as was the parsonage. The Abregos, 44 and 57, the wife being the older one (he’d been 22 and she 35 when they married!), had come from Matagorda, Texas, cattle country, and settled in Goosport where he was a machinist at a lumber mill, and they had indeed bought the old church building across from the cemetery. In the process of looking for a photo of the old church, which I have yet to find, I discovered that Steven Abrego was Sarah’s 3rd husband, after she had had to bury two, the first when he was only 25, allegedly hanged by cattle rustlers at Elliott’s Ferry on her father’s land (her maiden name was Elliott). I can well imagine him chasing the thieves, catching up to them at the river where the arduous job of ferrying a herd of cattle across a river could take all day, then the thieves, not willing to run away without the fruits of their theft, or lose them to a stampede started by a gunshot, deciding to simply throw a rope over a branch and killing him in relative silence. I have no idea if that’s what happened, but the picture comes easily to my mind, knowing how sturdy, but pains-takingly slow, managing those big old, hand-pulled ferries were back then. She’d also had to bury 5 of the 11 children she’d given birth to across her 3 marriages. In 1907, they had 3 of her surviving 6, Claude(37) a fireman for an oil company, Maud(16), and Vivien(15), both of high school age.

🎶Here’s one for you, Tisolay, something I’m pretty certain I can guess correctly. I found an article in the Lake Charles paper dated May 15, 1930 about Mr. Abrego, “Cabinet, Begun 41 Years Ago, Is Now On Display”. . . 5’10… mahogany… inlaid and overlaid… exquisite beauty and workmanship… carvings as intricate as lacework… a machinist by trade, and evidently an artist in spirit… begun in 1889 [which was just a couple years after they got to Lake Charles from Texas] and finished only a few days ago… appraised for $1600 [that’s 1930 dollars, $28,000. today!]… in the Ryan St window of the Milford Furniture Co. so that the public may have the pleasure of seeing it.” It wasn’t for sale, just display. I started thinking, what makes a person pick something back up that he laid down decades ago? I guessed, but sorta knew already. I went back to his wife’s date of death… sure enough, 10 days before the article was written. I had a picture of her, I think from her early days in Lake Charles before they were on Moss St.

I found one of him, too, a faded headshot of him as an elderly man. Later, though, when I went back looking for the article, I happened upon the full shot that the headshot had been taken from. And look what I found!

The best part… I think you must have seen it. You were 25, graduated and back home, teaching, teaching Betty as a matter of fact, among others, and you weren’t due to get married and leave for another 11 months. You remember where Milford Furniture was?.. I can’t get over this! Where Mathilde’s shop was, 613 Ryan, the one she bought with the railroad money, Michel’s accidental death settlement. More to the point though, it was across the street from Smith music. You went there all the time, I’ll bet. And when you left, crossing Ryan again headed for home, you’d’ve seen Milford’s big glass window. I’ll bet you were at that window, looking at it, within a week of this shot being taken, the same shot I’m looking at right now, like you’re there watching the photographer take the shot . . . in the scene, just not in range of the camera. There go the hairs on the back of my neck again. 🎶

~~~~~ the Cemetery ~~~~~

Anyway, the Abregos and the Cordsens, both, woke up every morning to the sight of the Corporation Cemetery. Maude Reid seems to have had a special affection for the old place, where much of her family was, as well as some of Lake Charles’ earliest settlers. She spoke of it often in conjunction with the Reid family’s private cemetery on her grandfather Judge David Reid’s homestead.

” [Judge Reid’s mother, Mathilde Furth Reid, d.1869] was buried in the family plot on Grandfather’s homestead, just beyond his cotton gin… A fence was built around the plot to keep out wild animals, as is customary in the country… A few months later when the old Corporation burying ground – as the Moss street cemetery was called for many years, was fenced in and became the Protestant burying ground, Grandfather had the remains removed to this spot. But if any marker was ever placed on the grave, it was long ago lost, there is no trace of the grave today… In the same family burying ground… were buried several children born to Grandfather and Grandmother Reid who died in infancy. Grandmother told me that an Indian was buried there, too.” – Maude Reid

I don’t know about the Reid family cemetery, but it was a long-held belief that the Corporation Cemetery is situated on an old Attakapas ‘Indian’ mound.

Miss Maude talks about having to transfer the rest of the Reid graves in the family cemetery when Abraham Moss bought the part of the Reid homestead where the old house and cemetery were from Judge Reid’s estate after he died in 1881. By the way, Abraham Moss was the father of both A. H. Moss, the druggist from Railroad Ave, and Emma Moss who married Alton Foster, a wealthy rice mill owner… who, many years later after Emma’s death, together with his second wife, were guests at my grandparents’ wedding breakfast in April of 1931 in which their daughter Blair, one of Tisolay’s piano students, was a flowergirl. (Echos are ringing in my mind’s ear of a 1970s New Orleans gossip columnist, the mother of a girl I went to school with, who loved to sign off with, “… but you knew that‘“.)

“Like the other old cemeteries, many of the graves have disappeared, and where once it was not possible to walk two feet in any direction without touching a grave, there are now wide areas where no grave is visible.” – M.R.

About that: I’m sure there were records in the church… that no longer exists, and its replacement on German/Ford St… which no longer exists, and the old City Hall… which burnt to cinders in the Great Fire of 1910. Didn’t anyone just go in and write down the names of who was there? Yes. Can you guess who? The queen and beating heart of Lake Charles history bemoans the fact that she didn’t do it soon enough to get everyone. S’okay Miss Maude, you did more than anyone else. When you consider what she ended up doing with her life, being the first official school nurse for the public school system, even going out into the poverty stricken areas and tending to children who didn’t go to school, or quarantined areas where children were in bed with cholera, and compiling the history of the town she loved for tomorrow’s children, though she never married nor had children of her own, it makes sense that she devoted her life to the well-being of other people’s children.

In her listing of names, she also noted “quaint and interesting epitaphs” she found while walking through the graveyard like, “… a large brick tomb from the 1890s of a merchant’s wife who died in childbirth… with molded hearts on top and around the sides as though to show how much she was the heart of her family, and that they buried their hearts with her”. She wrote of her emotions, “… the large number of babies and little children buried in them. Such an appalling waste! ” And then there’s the story of the J A Bel lumber mill worker who stopped into the saloons of Battle Row (Railroad Ave) on the way home one night and got so blind drunk that he wandered off the path that ran alongside the cemetery, somehow got inside the cemetery fence but couldn’t find his way out in the dark, and finally crawled up on top of a large tomb and fell asleep. The next morning, woken by the chatting voices of men going to work, he stood up on the tomb and yelled, “Hey, there! How the hell do you get out of here?”, sending everyone running. Apocryphal?.. you be the judge 🤣.

As many cemeteries are, it was beset with maintenance problems and vandalism, going unmown for long periods, and it could well be that all the Champagnes saw as they passed the cemetery that first day were weeds five feet high. In 1894 (Miss Maude would have been 12), the mayor, and then the newspaper, emoted about the desecration of a dozen or so tombs one Saturday night, “all molested, monuments and headstones being broken by some heavy instrument and fences and railing surroundings of some of the lots torn down and broken up… some of our oldest citizens… and little children.” Such a shame. New Orleans has its share of the same problems, every city does. But New Orleans is lucky to have a lot of volunteer societies that try to take good care of their historic cemeteries. One of them, where my Tisolay is, I’ll be in, the one in the Garden District on Prytania next to Commander’s Palace, a restaurant God would eat at if He thought He could get away unrecognized. That’s the one she and I so famously hopped the iron spike fence of one All Saints Day when we went to see Granddaddy too late, after the gates had been locked. But that’s a story for another time.

“It is a pretty site, upon a gently rising hill crowned with magnolia and live oak trees. . . . “ – Maude Reid, ca. 1960, at age 78.

No, not anymore, Miss Maude.

Well, if you don’t look up beyond the fence, maybe. But just after Miss Maude wrote the affectionate comment above, the Interstate-10 highway was cut through Lake Charles, right up to the southern fence line of the cemetery. If the Champagnes’ carriage were driving south from the railroad depot today, Moss would abruptly end (this part anyway) after a block and a half, just past the Cordsen house, with a blockade, a nondescript stretch of grass, a steel rail barrier, then 8 lanes of interstate traffic.

But Tisolay wouldn’t need to be concerned with that. When they got to the corner after passing the cemetery, they would indeed have seen the old parsonage on the left at 619 Belden St, same block, 3 houses down, now the home of Fred and Jocina Cordsen’s daughter Marie, her tractor salesman husband of 2 years, John Pitre, and their new baby May… whose middle name was Jocina.

~~~~~ the School and the Kinders ~~~~~

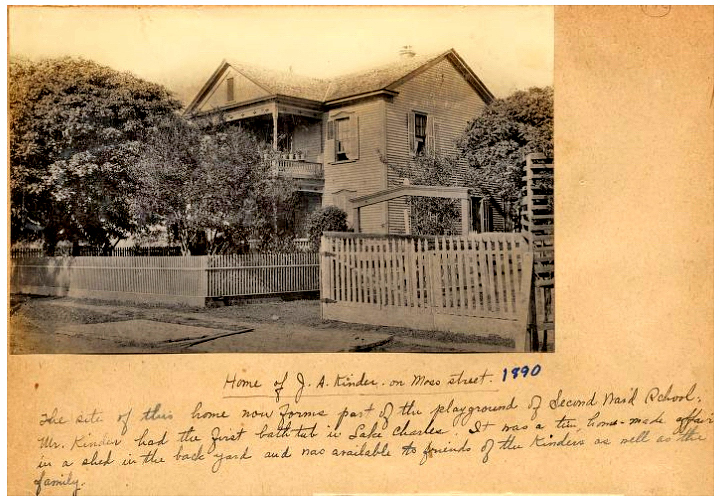

Across from the old parsonage house on Belden St, they’d have seen the 2nd Ward Public School on a big corner lot.

Tisolay’s 2nd cousin Kinta Babin, a year younger than her, would go to school there when they moved to Lake Charles a couple years later. Her daddy and Tisolay were 2nd cousins, though there was a generation between them, both being great-grandchildren of the intrepid Marie-Thersile Thibodeaux Babin (she had 22 children over 29 years!) back in Breaux Bridge. It would seem like a remote relationship, but they and their parents plainly knew each other because Kinta was one of only a handful of children invited to little Stella’s 9th birthday party.

Miss Maude’s not quite right about the school being on the site of Jim Kinder’s home. James A Kinder was from a family of Irish Canadians who moved to the Illinois region in the 1850s. He and his brother Sam, Union soldiers during the Civil War who fought in Louisiana, returned after the war and settled in the Lake Charles area, getting married in the mid-1870s to 2 Scalley sisters from an Irish family in New Orleans, building homes next to each other on Moss St., and going into the saloon business on Ryan St. Sam bought a house nearby some time afterwards, closer to the lake, and I think it was his house that was sold to the school.

Some time between 1895 and 1900, James being in his 50s, he went into the life insurance business, and that’s what he was doing when the Champagnes first drove past his house in 1907. He was 64, living with his wife of 32 years, Kate (51), and his grown son James, who worked for the SP Railroad as fireman and engineer through the years, but would soon marry a Texas girl and move there to work at the docks.

~~~~~ the Jacobsens ~~~~~

Across from the school and the Kinders were two houses belonging to the Jacobsens, mother and son, the family of Simon Baker Jacobsen, Jocina’s brother. Gardina Goos Jacobsen, the mother, now 64, is on the corner in the older house of the two, built in 1876 by her husband Simon. He had bought the large lot on the edge of the fledgling settlement from Jacob Ryan for $750 that summer, a few years after arriving with his young wife to captain a schooner for Daniel Goos, his wife’s uncle.

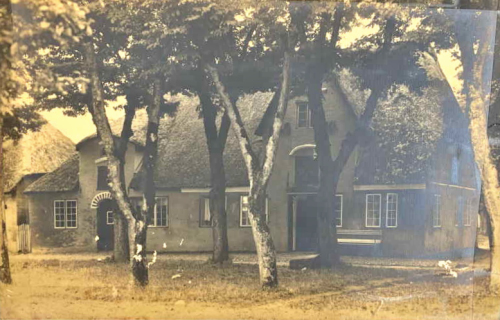

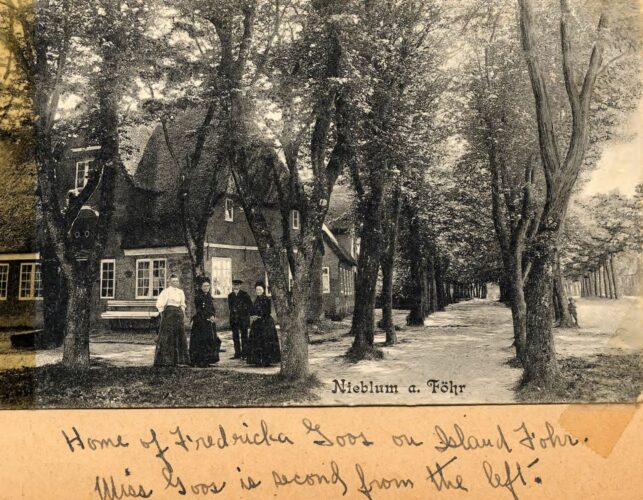

Foehr Islanders both, Simon and Gardina had gotten married in St Johannes Evangelical Lutheran Kirche outside of Wyk on Foehr Island, a massive medieval, 13th-century church beloved enough to Lake Charles’ Foehr Islanders for them to name the new German/Ford St church after it. The Frisians apparently have a marked love for their homeland and a loyalty to their distinct culture, which they consider separate and apart from either German or Danish. For a while, Lake Charles was proud of it, too.

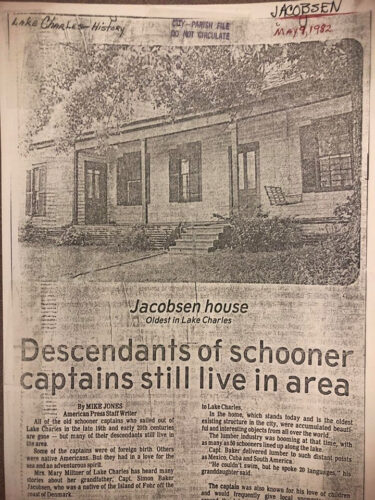

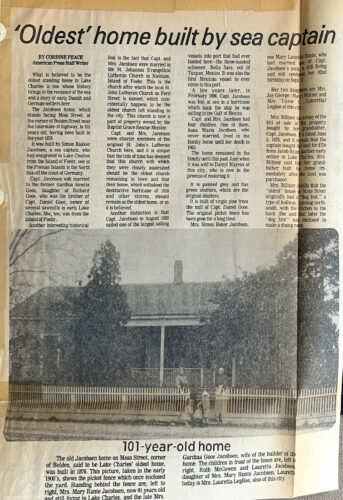

Lake Charles touted the old Jacobsen house as the oldest house in Lake Charles, but there were no pictures of it in their archives except those from 2 newspaper articles, from 1977 and 1982, about the legacy of the old Foehr Island schooner captains who made their mark on the character of the town. Found in several venues, both originate with Jacobsen granddaughter Mary Miltner.

Gardina took her children across the ocean more than once to get to know her family, friends and birthplace, and I found an eye-catching blurb in the Lake Charles newspaper about one trip concerning their anticipated return. It announced that their departure from Foehr was being postponed until their little son, Simon Jr, could recover enough from an accident where he got his foot mashed under a thresher which required the amputation of his big toe. (In the memoire of his future wife, she said they met at a dance, but that he didn’t dance, they just talked. )

. . . . . . . . .

🎶 Tisolay, were you aware of the Frisian identity of these people? There were still some 1st generation Foehr Islanders around when you were growing up, grandparents of your school friends, maybe. Gardina lived until 1931, the year you got married and left, and her house was described as being filled with exotic things that Simon brought home from all over the world. Of course, that doesn’t mean there were things representing their homeland, which wouldn’t have been exotic to them. But sentimental, yes. Did you hear people talking about ‘the old country’? Recipes? Notice their accents? Hopefully they weren’t like you . . . 🤨 . . . saying not one peep. God, how I had to drag what little of your story I got out of you. Nevermind… It’s some solace that I’m hot on the trail of your hometown and the people and events around you, if not you, and that these nice people are reading about you.🎶

Which, by the way, thanks, all 🌎😘. She’ll live forever because of you.

Anyway, when Simon was 17, a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico sank his father’s ship and made him the man of the house to his mother and 2 sisters, and he stayed near his mother for the rest of his life.

The year that the Champagnes’ carriage took them for their first ride down a Lake Charles street was the year Simon got married and built his bride a charming little house next door to where he grew up. He was a 30-yr-old engineer with Southern Pacific Railroad when he married Mary Runte, who was the oldest of 6 children who’d been orphaned 7 years before when they were between the ages of 14 and 3. They’d initially gone to live with their grandfather and his 37-yr-younger wife, but he died 5 years later, in June of 1905 (through some form of paralysis from 2 shocks sustained over 3 weeks🤔). The children asked their uncle to take over their tutorship and let them live by themselves in the care of 19-yr-old Mary, the oldest, under his supervision, which he did, renting them a house a couple blocks away from him. The Jacobsens were a block further.

Simon and Mary wasted no time presenting his mother with a new generation of children to devote herself to. He, or someone, took pictures of her with one of his daughters (Lauretta, who was 3 years younger than Tisolay, almost to the day) and one of his sister’s children, Blanche. They included glimpses of the back utilitarian part of the house, with a back shed and a cistern, showing me a tiny part of Tisolay’s neighborhood at the time she would have seen it, as though she were there, just 2 blocks away. She was there, 2 blocks away, 6 yrs old in one, 14 in the other.

For all the attention that Lake Charles’ preservationists tried to bring to the old Jacobsen house, especially after Gardina’s daughter Annie, the last of the family to live in the house, died in 1967, the house fell to demolition in 1985. The newer house, Simon Jr’s, fared better. His widow Mary died in 1985 and the house was sold and restored, but after 40 years, the termites had found its foundation, and the 2020 hurricanes did what hurricanes do. I didn’t know this when I saw Google Earth’s 2014 street shot of the charming little cottage, and happily added it to the list of houses I would make sure to visit and say hello to when Covid let up and I could take my long-awaited trip to Lake Charles. When Google Earth updated their 2022 street views not long ago, I was stunned. It was gone, now only a big green lawn.

~~~~~ The Mitchells ~~~~~

Back to their left, the last house the Champagnes passed on the block was the Mitchells on the corner of Lawrence St, recently renamed Pryce, deeply set behind a large front yard. Maude Reid has pleasant memories of the Mitchells and their house. “Col. Mitchell, one of the early lawyers, and a veteran of the Mexican and Civil wars, designed this house following the style of old Texas frontier houses. Every room had a door opening onto the gallery which ran all around the house. This old home has pleasant memories for me, because of the kindly Mrs. Mitchell who never failed to give me a generous handful of Japan plums from her fine trees when they were bearing, whenever I passed her house – and I always did – in plum season.” – Caption by Maude Reid, from the 1930s.

Col. Absalom Mitchell, born in 1821, was from Tennessee but moved with his family to east Texas near the Louisiana border where he became a lawyer. He remained a single man for 43 years, going to war in his 20s for Texas against Mexico in 1846, then again in his 40s in the Civil War. He finally got married right in the middle of his stint in the Confederate army to a young widow with 4 children. He and the “kindly Mrs. Mitchell” had 2 children, his youngest, Absie Jr., following his father in both name and the profession. He moved his family to Lake Charles when he was in his 60s and probably did live to see his wife give little Miss Maude some Japanese plums off of their trees when she walked by, but he died in 1894 when Maude was 12. He may or may not have seen, however, Absie Jr. marry since I find conflicting dates for the marriage on either side of his death. The kindly Mrs. Mitchell of Miss Maude’s memory died the year the Champagnes arrived, and it would have been Absie Jr (36), by then a District Attorney and legislator, and his wife Blanche, 32, together with their 5 kids (and another on the way) living in the house when the Champagnes rode by. One boy was Roosevelt’s age, the next 2 girls were within flirting age for both the Champagne boys, and Iona Mitchell was the same age as little Stella. They moved, though, after 1911, when Tisolay was 6, and the family of Rosa Hart bought the Mitchell house. Rosa was 12 then, and destined for considerable local fame as the intrepid and strong-willed creator and director of the Lake Charles theater. But they, too, were short-lived in that house, which sheltered several rental tenants after that.

The house behind the Mitchells, 619 Lawrence, which I can’t show you either an old or a new picture of, would be the home of the Babins two years later, Kinta’s family, Tisolay’s cousins from Breaux Bridge. Willie Babin was a laborer who eventually became a carpenter and builder, and though he was renting, he made significant design changes and expansions, which seems odd to me unless the owner hired him to do them. Ten years later, after they moved to the Margaret Place neighborhood, the new owners, the Murrey family, were told that the home was believed to be haunted, and that some time previous to their ownership, “there had once been a murder committed in the house and the body buried beneath the front rooms. A square cut into the floor where the living room and dining room are joined seemed to substantiate this belief – Mrs. Lloyd Barras”. Hmmm. Did Tiwazzo know what kind of man her cousin was? Were the occupants before the Babins burying the body at the very moment the Champagnes’ carriage first drove by? 😉 Actually, the grate for a floor furnace was typically placed between the main front rooms where guests would be.

~~~~~ the John Martin Reid house ~~~~~

Across from the Babins, the corner lot was much the same as the Mitchells’. Side by side facing Moss St, with Lawrence St between them, it too was a large corner lot whose house was set at the back of a deep front lawn. Until 1899, it had belonged to John Martin Reid, the brother of the pioneer carpenter> Sheriff> Judge David Reid, and a peaceable man very different from the hot-headed lawman. He’d had very bad luck with wives, burying two and divorcing a third who was nearly 30 years younger, unfaithful, childish and ‘Frenchy’, to use Maude Reid’s word, which I assume is ‘code’ for emotional and flirtatious. And he’d also been bullied, Miss Maude suspects, into taking the position of Sheriff for one terms when his brother first vacated it to become Judge. But he settled in well with his 4th. Good things are written about John Martin, who was helpful to his nephews during their irascible father’s many temper tantrums.

“This house has had a dormer added to the front roof, and the big, double-hall, or dog-trot, that we liked so much has been walled in as a modern hall with a very modern porch. Otherwise, the house is unchanged. No longer, however, does it sit back in a field looking to the west on Moss Street. It is now very neat and tidy on a bit of a lawn fronting on Lawrence. The side entrance was always on Lawrence, it was merely turned around, when the home was sold after Uncle John’s death (c.1899)”– Maude Reid

I don’t think it was sold right after his death, though. It must still have been in the family 12 years later when his nephew Andrew Jackson Reid died, because his widow pushed the house to the back of the property, turning it to face the side street, across from the Babins, and then built a large 2-storey house in its place for their eight children, facing the side street as well.

~~~~~ the Richards-Jessen house ~~~~~

On the corner opposite Moss St from the Reid enclave is one of those oak trees that makes whatever house it belongs to look wonderful, its long, low, outstretched arms blanketed with resurrection ferns. Still. It survived the storm. A wonderful house in its own right, retaining its original pioneer style, it hints at the story of the Jessens, another Foehr Island family of ship captains that married into the Goos family.

In 1907, this was the home of the widow Emma Goos Richards(53) who was living with her youngest child, daughter Relief(23). After Relief’s marriage that September to a shoe merchant named Maurice Rosenthal, he lived there, too. She built or bought the Lawrence St house one block down from her cousin Gardina Goos Jacobsen upon returning to Lake Charles with her 5 children some time after being widowed in New Mexico in 1885. Daughter Georgiana soon married Emil Jessen, a tugboat captain from Foehr Island, and her 3 sons did well in the lumber business, buying mills north of Lake Charles. Emma and the Rosenthals moved, though, around 1912 to a fashionable new neighborhood that was developed in response to the 1910 fire, and rented out the Lawrence St house.

Emma’s husband, Edward Wilson Richards, was born in Maine, orphaned early, and went to sea to become a sailor, which led him eventually to the port town of Corpus Christi, Texas. There he met Daniel Goos who brought him into the lumber business in 1867, then two years later, gave him his 5th daughter Emma in marriage. Around 1883, however, having become interested in mining, he took his family to live in New Mexico where, two years later, he caught a chill from weather exposure that eventually killed him. It gave him enough time, though, to go to Lake Charles where his death at the age of 47 was reported as having occurred at the home of Catherine Jessen, 65, the recently-widowed wife of Albert Jessen, one of Goos’ Foehr Islanders. A decade later, Emma Goos Richards returned to Lake Charles with her children. Emma’s closest sister had married Albert Jessen’s nephew Emil, a tug boat captain who lived in the watery wilds of the river near the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. And after his wife’s death a decade later, within a year of Emma Richards moving her family into the Lawrence St house in 1896, Emil would take the Richards’ daughter Georgiana as his 2nd wife and bring her to live on his forested homestead at the mouth of the Calcasieu River. Perhaps Emil stayed with his aunt Catherine and uncle Albert, who never had children, when he had business to do in town, and met Georgiana around the neighborhood. The Richards house was rented out in 1912, though, and I don’t see Tisolay getting to know the Richardses or the Jessens in the few years their time periods in the neighborhood overlapped with the Champagnes’. Besides, so cliquish were these Foehr Islanders with the Goos family that Emma’s son Charles married his first cousin, the daughter of another of his mother’s many sisters.

~~~~~ the most recent of several Hutchins homes ~~~~~

Past the Richards home, the predominance of Foehr Island influence wanes in favor of the inter-relatedness of 2 other families much more rooted in the American pioneer experience out of New England, the Reids, whom we’ve already met, and the Hutchins family. The cluster of homes around the intersection of Moss and Pine belong to several Reid and Hutchins cousins, whose children no doubt grew up with the Champagne children. These 3rd generation Lake Charlesians are best met by taking the alternate route the Champagnes could have taken from the train depot, and seeing what the Champagnes would have seen had their driver taken Hodges St instead of Moss.

Finding the children in the neighborhood who became friends with the Champagne children, whose homes and families the Champagnes got to know in those first 3 years, played with, had sleep-overs and meals with, whose colds they caught … knowing that some of them were in the same room as the child my Tisolay was, the girl I love so much but know so little about, playing with the older Champagne children amidst gleeful toddler shrieks and pre-school chatter from elsewhere in the house, and occasional intrusions, sometimes holding her, talking to her, bouncing her, fending off her sometimes-unwanted intrusions, makes the hair on my arms tingle. So without further adieu . . . (cont’d on pg. 2)

~~~~~~~