(cont’d from previous post)

🎶I can just see y’all as a family in those first few days, from the moment someone carried you across the threshold, J Euclide overseeing the carriage driver bringing in trunks and boxes and what-have-you, maybe bringing up the ones destined for the bedrooms upstairs while y’all looked around everywhere, opening every door, checking out the views from the windows. I can imagine Tiwazzo, Beulah and Carmen tired from the trip but excited, unpacking trunks and boxes in a new house, cleaning as they went, . . . trying to corral the energies of an irrepressible toddler (you). Maybe they had to stop every so often to redirect 2 curious boys who’d rather explore than put their things away or help their mother and sisters set up their new home. Tiwazzo might have been wondering about the first meal she’d have to have ready in just a few hours, wondering where the grocery stores, butcher shops, fish markets, bakeries, etc. were. I can see the boys looking out the windows, perhaps waiting for your father who may have walked over to the freight depot a few blocks away to touch base with his new boss.🎶

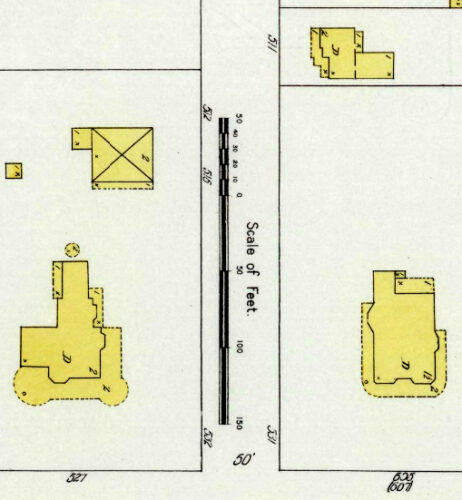

My grandmother had never said anything about living anywhere else but 617 Moss, where she lived from around the age of 6 or 7 until she graduated from college, so I was very surprised to see in the 1910 census, when she would have been 5, that the Champagne family had first lived a block away, at 511 Moss St. She had no memory of the 511 Moss house that her family had apparently first moved into when they got to Lake Charles. She was 2 or 3 when they moved in, and 5 when they had to leave it. A quick look on Google Earth for 511 Moss showed me that it was gone, the site now occupied by a modern little cottage. It was on the 1909 Sanborn map, though.

~~~~~~~~~~ 511 Moss St ~~~~~~~~~~

It was a 2-storey house with a large 1-storey “L” off the back and a 1-storey verandah in front spanning the width of the house. The verandah had two sequential insets that followed the two recesses of the house’s façade. I would guess there were 3 bedrooms upstairs, a parlor, dining room, and kitchen downstairs, and 2 additional rooms in the back “L”. The “L” didn’t have its own verandah, and may have been more integrated with the inside of the house than an independent unit with its own outside entrance. There wouldn’t have been pantries or closets like today since they were counted as rooms, and houses were taxed by their number of rooms. Armoires and cabinets were used instead. The recessed façade and verandah seemed more decorative than a house built to be a rental would have been, and I wondered whether it had once been a private home with interesting verandah columns and Victorian brackets, maybe a gable or two, but I was content with Sanborn’s precise footprint of it.

Some time afterwards, though, I was looking at a photo of the Bel mansion I’d had for a while, from a post about the families that initially settled the neighborhood, and noticed something I hadn’t before.

It had been taken at an angle that included the side street where 511 Moss St would have been. And there, peaking out almost indistinguishably through the bare winter branches of a tree, from behind a white-picket-fenced hedge, were the dark shapes of a second-storey roofline and a 1st floor verandah roof, with vague hints of windows (you gotta want it).

The photo was dated 1905, only a couple years before the Champagnes would move in; before Tiwazzo, Beulah and Carmen would stand in the kitchen unpacking things into that house in the photo, peaking through the Bel’s winter trees. The view in this photo, from 118 years ago, was nothing like the view today which is blocked by rows of massive oak trees that, though lovely, hide any sense of the surrounding countryside or horizon. But Maude Reid gives me an inkling of how this photo represents a different town than any I could know today. “Looking to the right can be seen a few pine trees and one or two homes – showing how sparsely settled this section of the town was even at the time this picture was taken, 1905.” This photo is of my little 2½ year old Tisolay’s home almost exactly as she saw it and lived it, and it sorta makes the hair on my arms stand up.

🎶I tell ya’, Ti. You may not have told me anything about this time in your life, but that doesn’t mean I couldn’t find out things in other places. I used to ask you stuff, and it was always, “Oh, I don’t remember” or “I never paid attention to such things back then”. Yeah, well, that was back in the ’80s, before there was any such thing as the internet.🎶

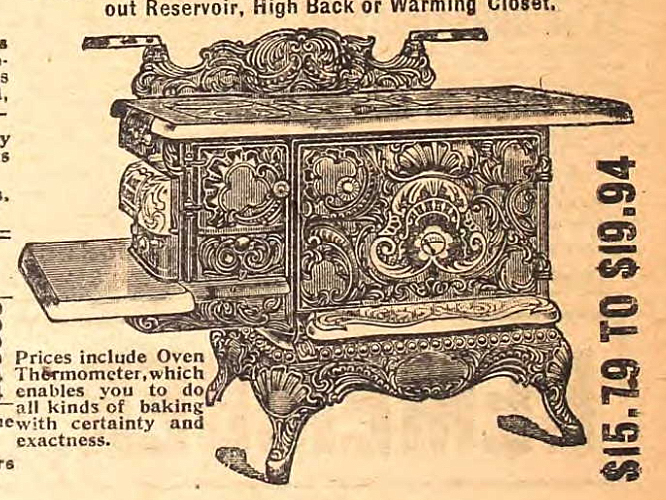

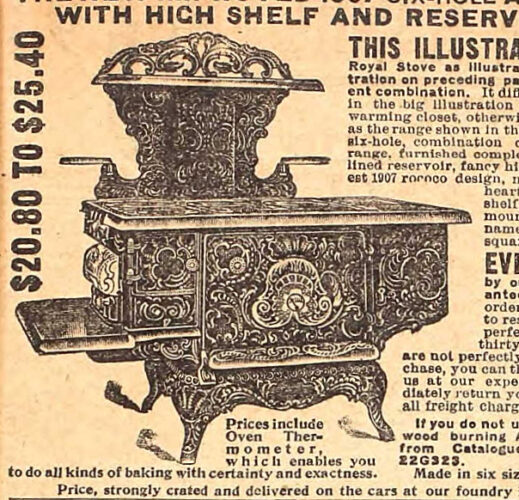

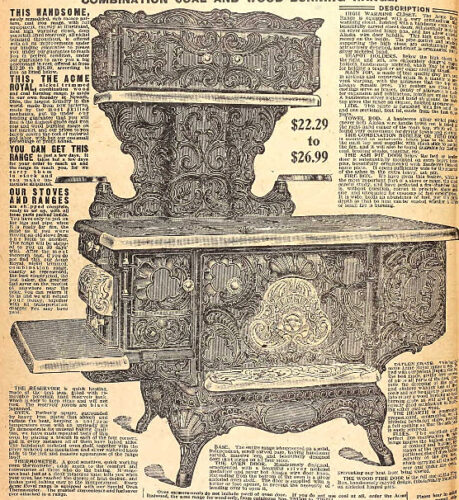

~~~~~~~~~~ 1907 Sears catalog ~~~~~~~~~~

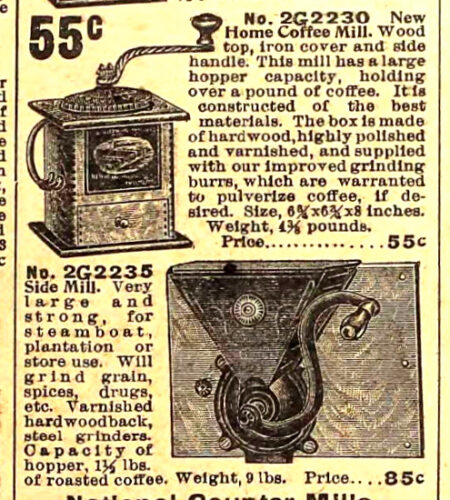

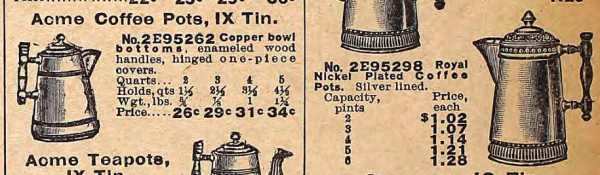

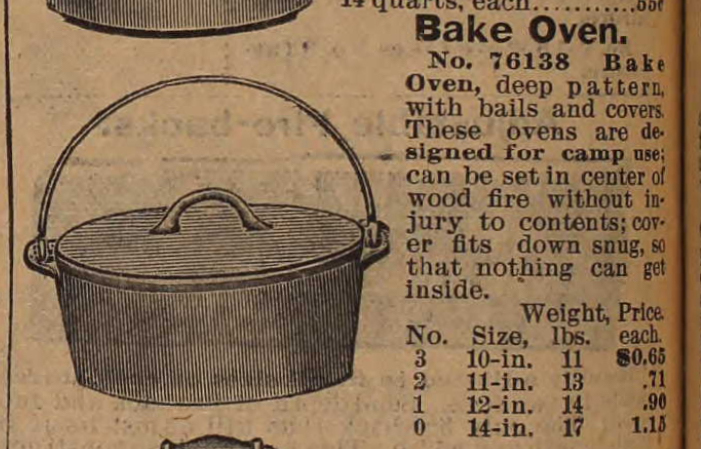

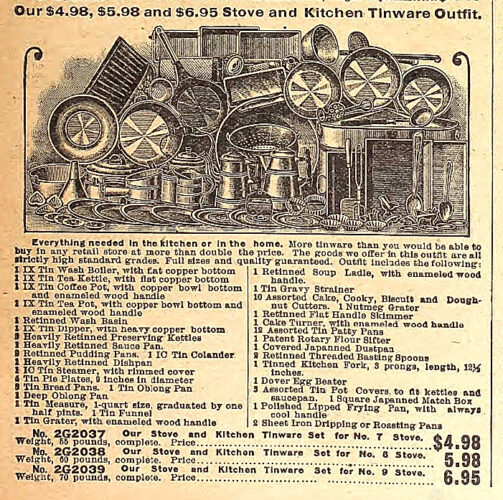

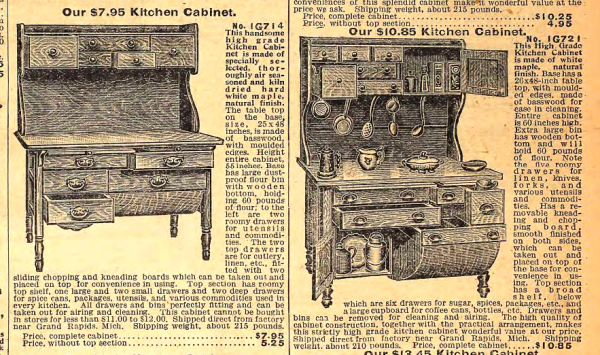

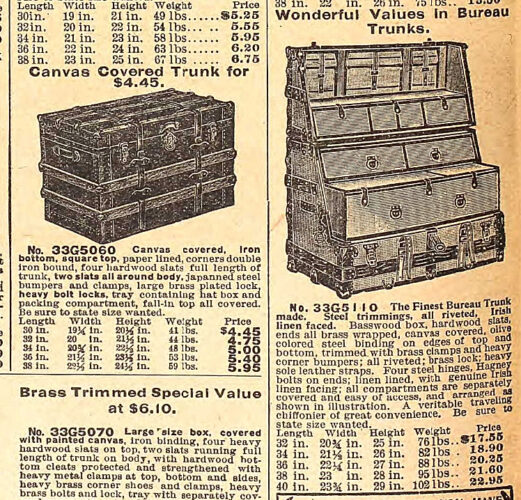

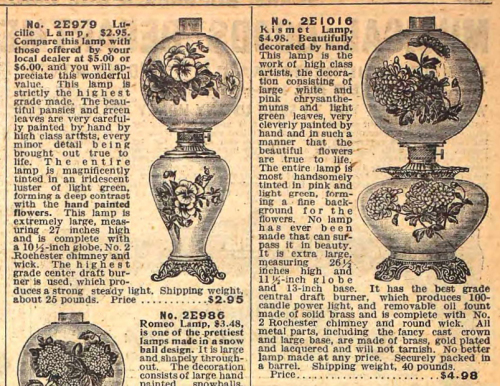

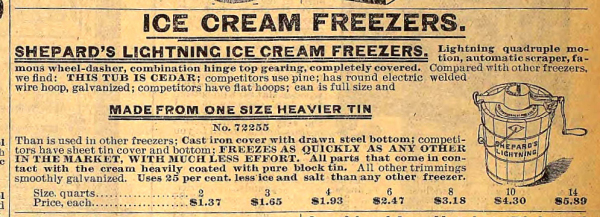

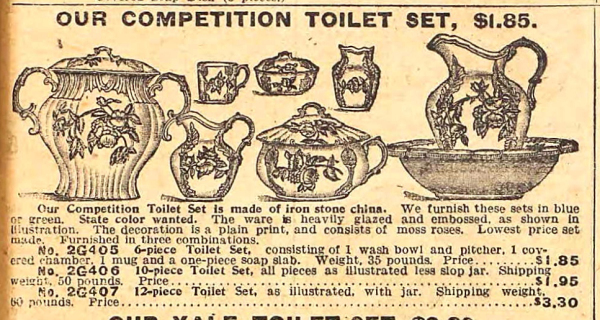

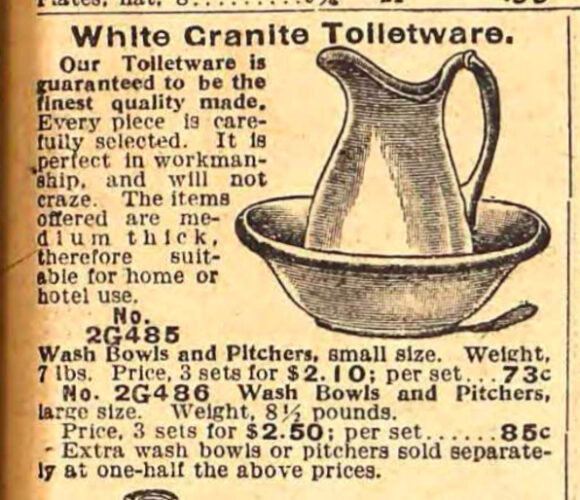

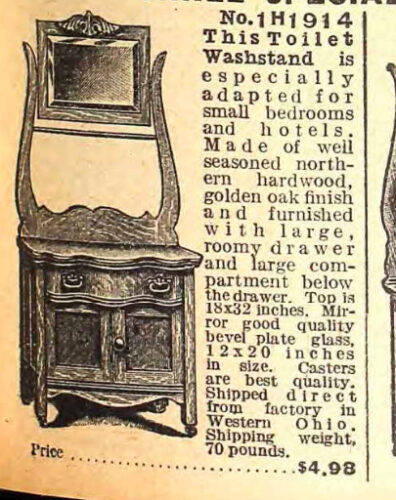

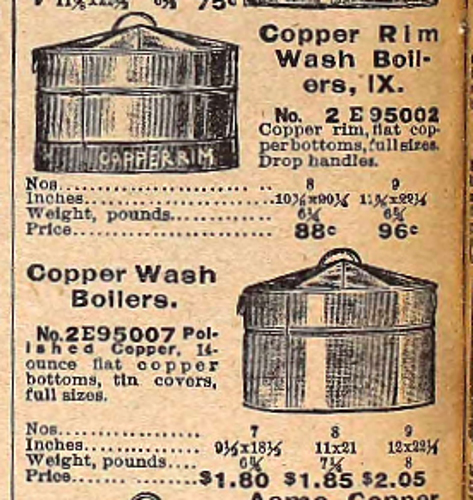

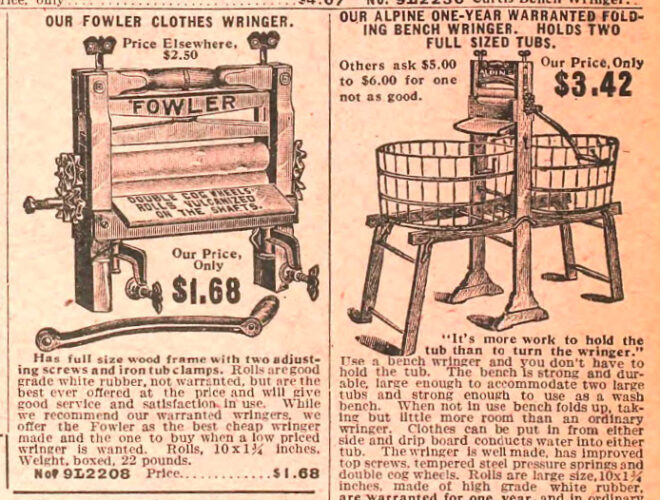

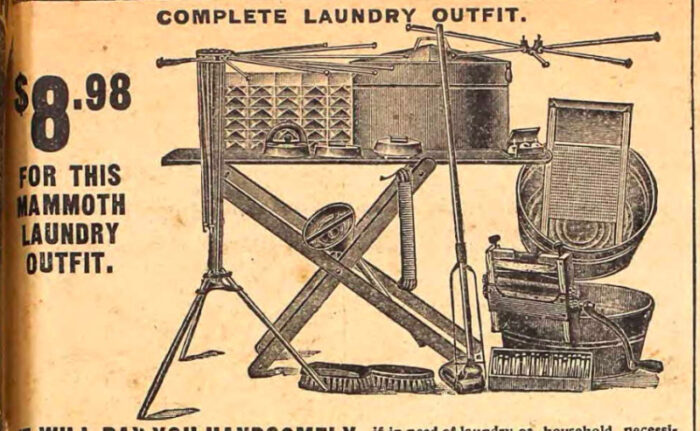

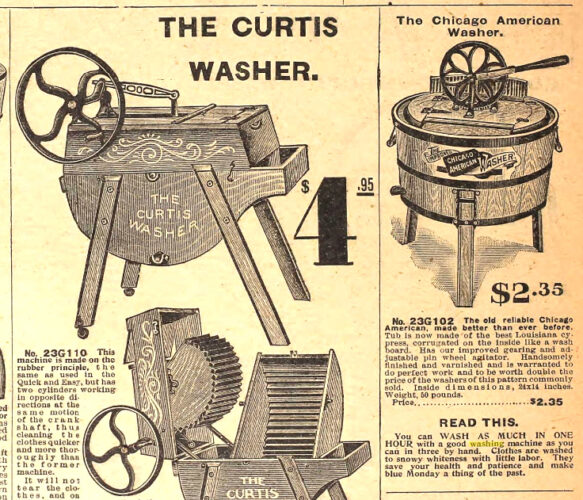

So often I find that Google rabbit holes, especially when they’re about things I wouldn’t have known to ask about, can be worth their weight in gold. One of those began with an old illustration of a wood-burning stove from the Sears catalog. Through that, I found that Ancestry.com had all the old Sears catalogs online… in particular, the 1907 catalog. And in one fell swoop, I got 1382 pages of visuals of my grandmother’s childhood, everything (and I mean everything) she would’ve seen and touched and lived amidst as she toddled along with her family to their neighbors’ homes, to church, to the schools and stores and offices in her family’s world. It gave me my first glimpse of the things in her own home that she watched her her sisters and brothers and parents use as they buzzed from room to room around her, and the day-to-day activities for which they were used. I rejoiced in the catalog’s precise and detailed illustrations. Just as informative, after I looked up the comparative value of the dollar between 1907 and 2023… (Ready? . . . sitting down?. . . one 1907 dollar would be worth $31.50 in 2023 dollars.) … just as informative were the prices and being able to grasp the relative cost of things that would have fit into the Champagnes’ limited budget, and the finer things she would have seen in her wealthier neighbors’ homes. The hype and hyperbole in the descriptions made for many eye-rolls and full-out laughs, but there were also informative explanations, diagrams, and cross-section drawings of how things worked, things we don’t use anymore.

🎶Man oh man, Ti, have I ever fixed your wagonload of “I can’t remember”s!!🎶

~~~~~~~~~~ stoves ~~~~~~~~~~

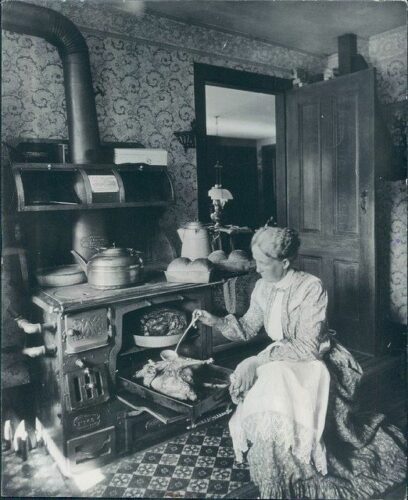

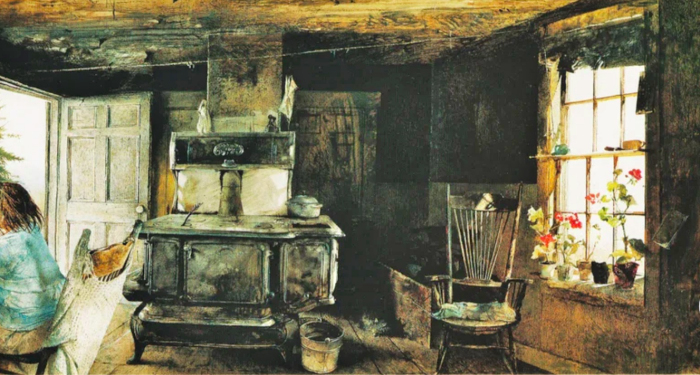

Anyone who knows me knows I’ve been into ethnic cooking since my mother and I had eaten our way from one end of Europe to the other. I’d moved from the college dorm to an apartment and started equipping my first kitchen from a local cooking school that had a store with cookbooks from all the countries we’d visited, and for about a year, I bought one from a different country with every month’s food budget, and cooked from it for 2 weeks, then decompressed with regular food for 2 weeks. Being from New Orleans, we’d taken visitors to historic houses and plantations for as long as I could remember, and I’d always loved the kitchens, mostly the later ones that had massive old wood-burning stoves, the ones with beautiful floral curlicues in the heavy cast iron. The first time I asked Tisolay if her family’s kitchen in Lake Charles had had one, I was disappointed that she didn’t remember, didn’t remember anything about the kitchen. For years I tried to get her to remember what kind of stove had been in her kitchen. Nothing.

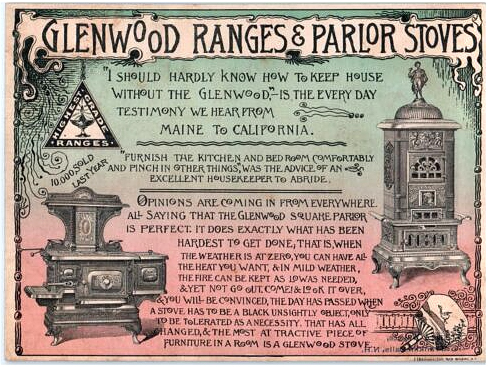

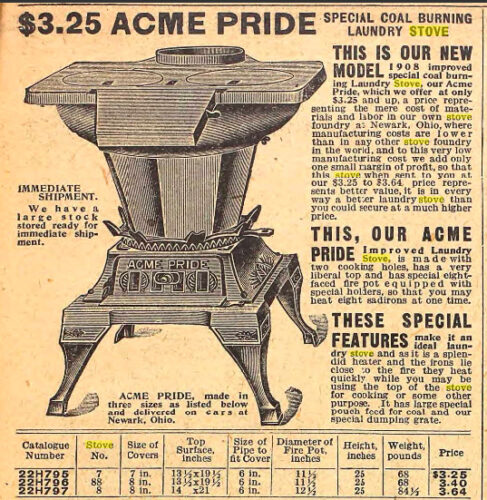

So when I first stumbled onto the section of pink pages Sears put in the middle of their catalogs and found that it was an index, I made a bee-line for the stoves.

I was thrilled at the pages of crisp, detailed pictures, but got really excited when I saw that Sears had devoted nearly an entire page to a diagram explaining what all the little doors and slots and gewgaws were for. All the different models, each with various add-ons to choose from, made me wonder what kind of stove Tiwazzo was used to using and which features she would have seen as necessities and which as extravagant. I didn’t know, but given my foresight into the changing times and technologies that were about to set turn-of-the-century housekeeping on its ear, I knew what I wanted her to have. She needed one that burned both wood and coal since she now lived in a town and no longer had access to her father’s big tract of wooded land nor his variety of wagons in which to bring firewood home. And I wanted her to have a bigger stove than the one her father Adeo might’ve first put in the house down by the water when she first got married. I didn’t get extravagant, but with a family of 7, I did give her 6 burners and bumped up the oven to the middle of 3 sizes.

I chose a model with those specs, the Acme Royal, that came with different levels of bells and whistles, at different costs, and I used it to exercise both my understanding of how the stove worked and my grasp on the whole 1907-2023 money-comparison thing .

It wasn’t long before I started to see that a hot water reservoir was too much of a time saver not to spend the extra 2.85 ($89.77) for it. The high shelf, at an additional 2.36 ($74.34) and warming closet at 1.49 ($46.93) seemed unnecessary, but my reading had given me a sense of how labor intensive life back then was, and operating the stove in particular. Wow, but these monsters were a nightmare to use!

“Ashes from the previous fire had to be removed. Then, paper and kindling had to be set inside the stove, dampers and flues had to be carefully adjusted, and a fire lit. Since there were no thermostats to regulate the stove’s temperature, a woman had to keep an eye on the contraption all day long. Any time the fire slackened, she had to adjust a flue or add more fuel, and throughout the day, the stove had to be continually fed with new supplies of coal or wood – an average of fifty pounds a day. At least twice a day, the ash box had to be emptied, a task which required a woman to gather ashes and cinders in a grate and then dump them into a pan below. Altogether, a housewife spent four hours every day sifting ashes, adjusting dampers, lighting fires, carrying coal or wood, and rubbing the stove with thick black wax to keep it from rusting.” Digital History topic ID 93, Housework in Late 19th century America

And that was just the kitchen stove. There may have been heat stoves upstairs and a parlor stove that vented into the bedroom above. Most cost between $8 – $14, ($252 – $441) but could go up to $20 ($630.)

I liked the fact that many of these room heaters had a cook surface where a hot water kettle could be kept. Hot water on an upstairs stove, maybe in the central hall, might alleviate the need for so many morning trips up and down the stairs with pitchers of hot water.

And then there was the coal! Coal was delivered to the house and shoveled into a cellar or bin of some sort. At $5-6 a ton, which would be 40 days’ worth for the kitchen stove alone, that’s 12¢-15¢ a day, ($3.78 – $4.72).

You know what else Sears listed along with dimensions and prices? The weight!! These things weighed nearly 500 lbs., and it occurred to me that it would have cost a fortune to ship a massive cast-iron stove by train, even if J Euclide was an employee of the railroad now. And that was just the stove. Worse and more of it; Google told me that turn-of-the-century renters usually had to supply their own stoves for an unfurnished place. So, would Tiwazzo have had anything to cook on, even if they had been able to find food stores in the next few hours?

Well, they obviously figured it out. So let’s get back to what else would have been in Tiwazzo’s kitchen.

Since I’m used to thinking in terms of $10, $20, $50, & $100, etc., I soon figured out that taking the prices in the catalog, dividing by 3, then moving the decimal over two spaces to the right (multiplying by 100), got me close to today’s equivalent. Pretty soon 30¢ and 60¢ were the new $10 and $20. And $1.50 and $3 were just under the new $50 and $100. In any case, I’m putting the 2023 equivalents on everything.

I compared the above tinware set prices with what it would cost to get the pieces individually, and it really is an excellent deal, though there are a few things I wouldn’t use because I’d want them in another material. If I were Tiwazzo, I’d do what I did; visit the second hand store (in my case, flea markets), get a few of the old heavy iron things, then boil them clean and reprime them with seasoned oil in a warm stove for a few hours. And of course, for the sake of your knives, you have to have wooden chopping bowls and boards.

And come to find out, frying pans were called spiders then! Something about them originally having 3 metal legs to keep them up above the wood and ash of an open fire. Several of my vintage black iron pots are 3-legged, including a big Dutch oven with a tall-rimmed lid to hold coals on top for baking bread.

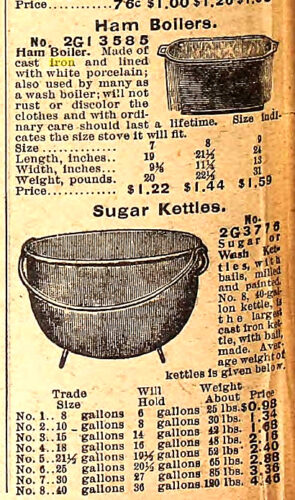

I saw a huge iron ham boiler in the catalog and wondered if Tiwazzo ever cooked ‘big’, like I do, putting away 10 qts of gumbo in the freezer, then remembered there were no freezers. She may have cooked big when she joined the Bourdiers at 617 Moss, when the household became 9-strong plus a roomer, but a pot that big in iron is very heavy and lighter metals were becoming all the rage.

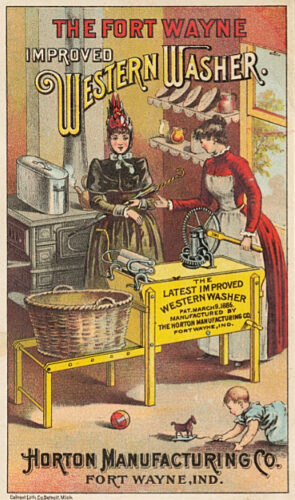

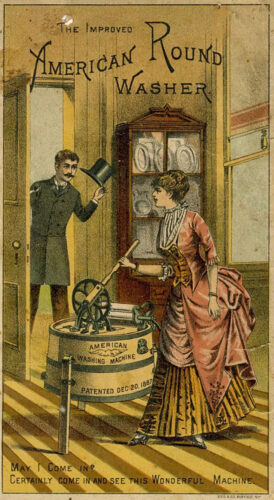

The sugar kettle made me think of things Tiwazzo and J Euclide would’ve seen being cooked on big open-air fires when they were young, back on the farm. Big cauldrons of gumbos, jambalayas, or boiled seafood at big outdoor Sunday dinners, holidays, weddings, maybe gatherings for community projects like putting up the frame of someone’s house. They also would’ve done alot with it during butchering season, like cook cracklins, render lard, mix boudin sausages, etc. Laundry was boiled, too, in their own pots. But would Tiwazzo still be doing big cauldron fires outdoors like this, either for food or laundry, now that stores were a block away and washing machines, albeit crude by today’s standards, were now available? It made me sad, somehow, to think that the outdoor tradition of the simmering cauldron at the center of a social occasion under the trees had run its course. George Rodrigue captured this Cajun tradition in some of his paintings, and my father’s uncle captured a family event outside under the oaks. My father’s father is standing at left amidst his 7 siblings, and old Papa Oscar Martin is in the center in a rocker, his back to us. Neither he nor their mother Corinne spoke English. Their grown children, all fully bilingual, would’ve only spoken their native French with them.

~~~~~~~

Eventually, I became hungry for more than line drawings: I wanted color, I wanted context, I wanted to see the things used in the rooms they were supposed to be used in. So back to google I went, where I found period paintings and vintage photos of domestic scenes that brought life to Sears’ printed illustrations, and gave me a glimpse of my little Tisolay’s life as it might have gone by around these stoves.

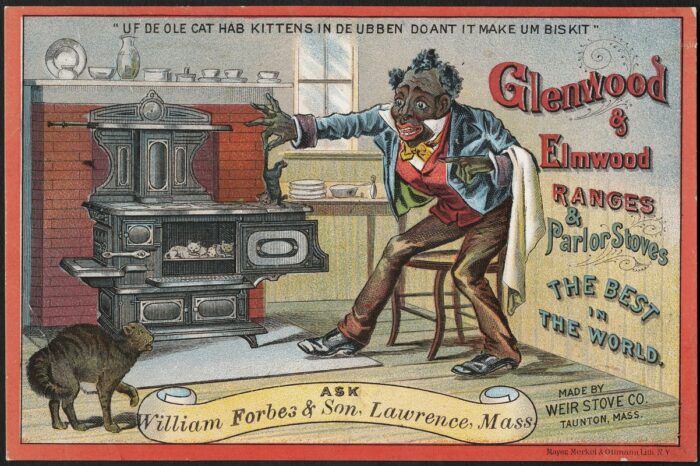

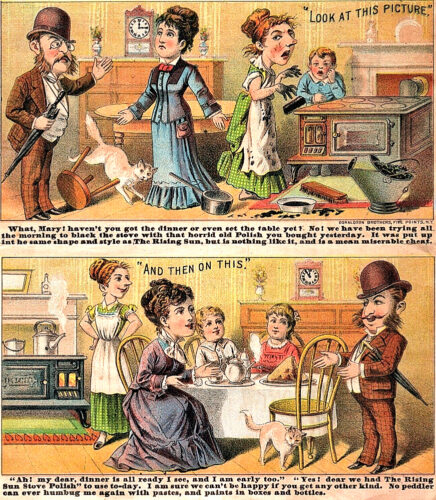

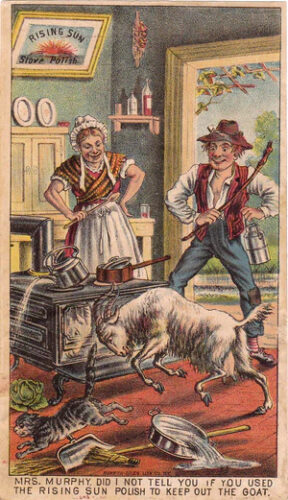

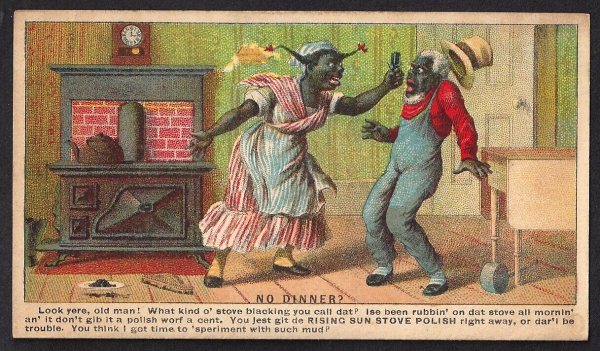

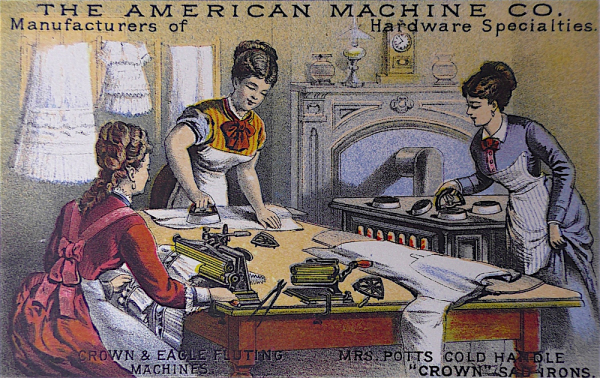

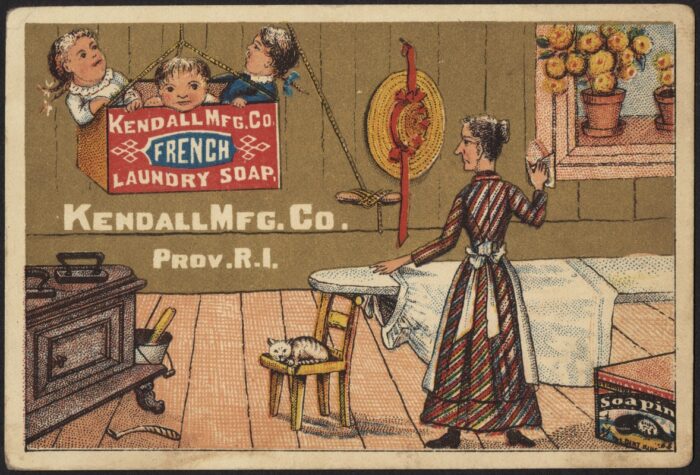

Northern foundries and iron works put out trade cards, brought south by salesmen, that depicted idealized domestic situations and caricatured cultural portrayals.

I don’t know where the whole ‘humbug’ thing is from, but I suppose it can be said that the Rising Sun stove polish people were equal-opportunity caricaturists, laying their humbug across all racial, gender and socio-economic lines.

“What, Mary, haven’t you got the dinner, or even the table set yet?” “No, we have been trying all the morning to black the stove with that horrid old polish you bought yesterday. It was put up in the same shape and style as The Rising Sun, but is nothing like it, and is a mean miserable cheat.”

“Ah, my dear, dinner is all ready, I see, and I am early too.” “Yes, dear, we had The Rising Sun Stove Polish to use today. I am sure we can’t be happy if you get any other kind. No peddler can ever humbug me again with pastes and paints in boxes and bottles.”

“… no peddler can ever humbug me again… “

“I never knew I was so fair, what lovely eyes? what curly hair? And what a most distinguished air? In fact, I’m very dollish”, said Cinderella, as she gazed upon her face, entranced, amazed, within the mirror she had raised with ‘Rising Sun Stove Polish. “My naughty sisters to the ball this evening go, their pride a fall shall have. I’ll see them there and all their stuck up airs abolish”. She met a Lord of high degree, who said ‘I ne’er can love but thee!’ So now she lives in luxury, through “Rising Sun Stove Polish”.

Alright, enough nonsense. Sears and Rising Sun has admirably slaked my 50+ year curiosity about black iron wood/coal stoves, but now it is beckoning me to come back and flesh out the kitchen.

~~~~~~~ kitchen cabinets & contents ~~~~~~~

Ok, who here doesn’t love the kind of kitchen cabinet that briefly allows you the delusion that your life is organized and orderly.🤣

Triple the price for a Hoosier is too much to pay for their flour sifter, but it sure is tempting, what with the spillage mess and multiple transfer containers that would no longer be needed.

~~~~~~~ moving (cont’d), shipping, furnished vs unfurnished ~~~~~~~

Back when I was first musing over that first moving day, when everyone would’ve been unpacking something, or cleaning something to unpack into, and Tiwazzo was wondering how she was gonna throw something together for dinner, I read somewhere that moving out of town for all but the wealthy meant having to sell everything you could and replace it when you got to your new location. So, did that mean that it wasn’t just the stove, but that they didn’t have any of their furniture? Did they even have a kitchen cupboard to unpack into? What about armoires and dressers for clothes? Did they even have beds to sleep on, those first few nights?

I soon learned that Lake Charles had a bunch of rooming houses, official and unofficial, the latter often run by widows with large houses and no income who fed their guests as well. So they could have stayed in one of them while setting up their house.

Still, imagining the Champagnes moving into an empty house was a bit of a shift in gears for me. The Sanborn maps from that time have several buildings labelled as second-hand stores, and it occurred to me that big money was being made in Lake Charles, especially after the railroad finally came through. Northern industrialists who got rich on Calcasieu Parish’ lumber were building grand mansions up and down Broad St and Pujo and Kirby, bringing with them a big-city culture with a more sophisticated mindset that included the arts, music, theater, literature, and an appreciation for fine things. And they could afford to ship their fine furniture down. Seeing their things, the wives of the newly-wealthy locals, would have surely ditched their old things and made their husbands keep up. I read in a Lake Charles history somewhere that furniture stores were only too willing to keep up, stocking furniture and fine things that this little frontier town had never seen before, so I imagine it wouldn’t have been long before the discards were cascading into second-hand stores.

But, my God, did the Champagnes really have to start from scratch in an empty house, living in a roominghouse until they could buy furniture? I just don’t see Tiwazzo being able to afford replacing everything she left behind, even second-hand, on a lowly railroad clerk’s salary. I found a graph of comparative salaries of jobs from 1910, and J Euclide’s job as railroad freight clerk, a relatively low-paying job, would have made him about $600 a year, equivalent to $20,000 today. Back then, 80% of what most people earned was taken up by rent, food, and clothing, food taking up half of that. So of the remaining 20%, say the Champagnes put 10%, $60, toward furnishing their new house. I can’t know what second-hand opportunities or prices Tiwazzo would’ve found, but the stove I would want Tiwazzo to have, new, would have eaten up a third of that. Besides, unlike people moving out of town who have some money from the sale of their things to buy replacements with, many of Tiwazzo’s things back on the farm had likely belonged to the house her father built for her when she got married. No, I think they’d need a place furnished with at least the bare necessities of furnishings. And if that were the case, maybe, if the Champagnes were unpacking their things into a furnished house, Tiwazzo and the girls might have been as free as I’d originally imagined to think about where to get things for dinner after all, and start their new life in a furnished home that very day, and explore their new town.

~~~~~~~ the light dawns ~~~~~~~

With the joy of seeing tidbits of Tisolay’s childhood on the pages of a 1907 catalog came twinges of guilt over the scope of my ignorance. It didn’t just show me the extent to which back-breaking, hand-wrenching labor was still the only option in running a household in 1907, but it symbolized the extent to which I didn’t know the forces that formed her. What had initially sent me off hunting for pictures of things that would have been in a 1907 household was a particularly “Duh!” moment in my first musings about their move. Maybe it was because I had just made a big move myself, to Oregon after a lifetime in New Orleans, that I envisioned the family divvying up boxes, leaving clothes boxes upstairs in front of the bedroom armoires for later, maybe digging out the basic toiletries to put in the bathroom. Then because hunger would set in before any other immediate need, the girls turning their attention to the kitchen, helping Tiwazzo unpack pots into their kitchen cupboard, wiping down surfaces. I had such a clear vision of them letting the rust run out of the unused pipes of the kitchen sink first, then when the kettle was finally unearthed, someone rinsing it out, filling it, then putting it on the stove straight away. Surely the white enamel drip pot would emerge before the water boiled. I wondered if they’d thought to pack a little coffee for that first day, and pictured myself grinding some beans before leaving and putting them in a ziploc, like I sometimes do on a trip.

I’d had in the back of my mind an image of a moving truck out front whose movers had finished bringing in beds and armoires and tables and putting everything in place, hooking up the stove, etc. Then the light dawned. Wait… reality check. Water from the sink to fill a tea kettle? A stove hooked up and ready to heat the water? Hooked up to what? There was no sink. There was no bathroom, because there were no water pipes… because there was no plumbing. I don’t remember what told me that, but it caused a deep shift in my vision of Tisolay’s childhood.

Lake Charles had only recently started running underground drains beneath the curbs of Ryan St and its intersections where only boards over a rain-filled ditch allowed people to cross the street at the corners. New construction for the wealthy northerners had all the latest technologies installed, but they were only beginning to hook these magnificent homes up to the city water or sewerage lines, themselves under construction. Wealthy locals with older homes, like the Krauses next door and the Goos family on the corner, had the money to retrofit their houses with hot and cold running water all through the house, and Sears carried the latest in sinks, tubs, and toilets for them, just as they carried the older necessities which the majority of people still needed, like the Champagnes. It would be a while before the average homeowner could modernize their old homes in this manner, and even longer before it was financially worthwhile to outfit a rental unit with plumbing.

🎶Oh, God. Tisolay. How dense can I be! I’ve studied your ancestors for so long that their back-breaking, labor-intensive lives, and the primitive tools they had to work with have has become second nature to me. And since I was born, you’ve been telling me stories about your life in New Orleans since you left Lake Charles to marry Granddaddy. But studying the past looking forward and the present looking back, it never occurred to me to think about the point where the two meet, which happened to be when plumbing and electricity came into use and changed everything about life as we knew it . . . which happened to be your childhood years, which happened to be the years you wouldn’t talk about, the Lake Charles years.

Still, how could I not see? Carmen and them wouldn’t experience much lifestyle change between the early years of Lake Charles and where they were raised, on the farm where no one had plumbing or electricity. But you would’ve started seeing the new technologies and the resulting lifestyle changes during your formative years, in the homes of your wealthy friends, in Karl Krause’s house right next door. I think I know when you finally saw these changes happen in your own home. The 1919 Sanborn shows changes to the back porch of the house that indicate it was probably between 1915 & 1918 when one end of the kitchen porch was closed in and retrofitted as a bathroom, and a second-floor duplicate of it built on top of that. Your formative years must have been defined by the awareness of both lifestyles and the dizzying parade of inventions and advancements that made change the rule of the day. How is it you never said a word about all this richness of experience and perspective🤨, especially when it became evident that my persistent interest in your ancestry was about to change the direction of my profession!

Nevermind. Here endeth the scolding….. maybe.🎶

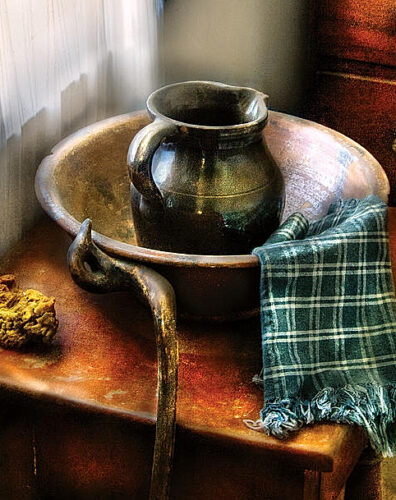

It took some doing for me to imagine my grandmother’s day-to-day life without plumbing or electricity, since I’d only known her in the modern house she was in when I was born, the house I inherited 47 years later. I still don’t know why since I had no trouble imagining her mother, Tiwazzo, growing up on the farm in Breaux Bridge in a house with no bathroom, bathtub, toilets,… bathing from out of a pitcher and bowl on a dresser and using an outhouse. But Tisolay? The utilities during her childhood consisted of kerosene for lamps after dark, ice for the ice box, and wood or coal for a stove that did triple duty cooking, doing laundry, and bathing people. How surreal is that compared to the machines, computer centers, internet, robots and AI that are sucking every drop out of our overworked power grids today.

~~~~~~~~~~ no running water ~~~~~~~~~~

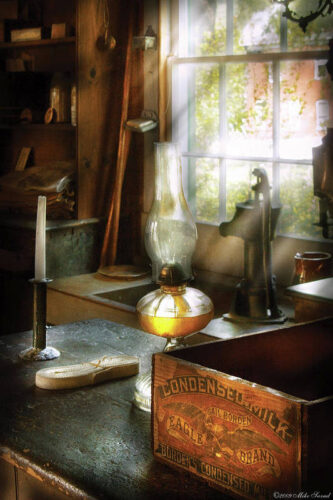

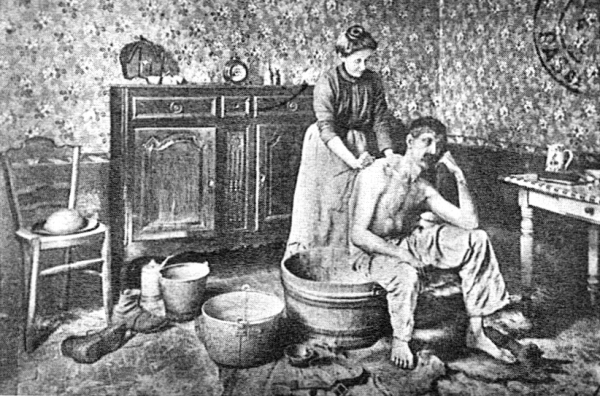

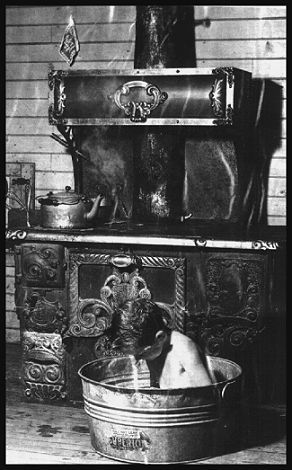

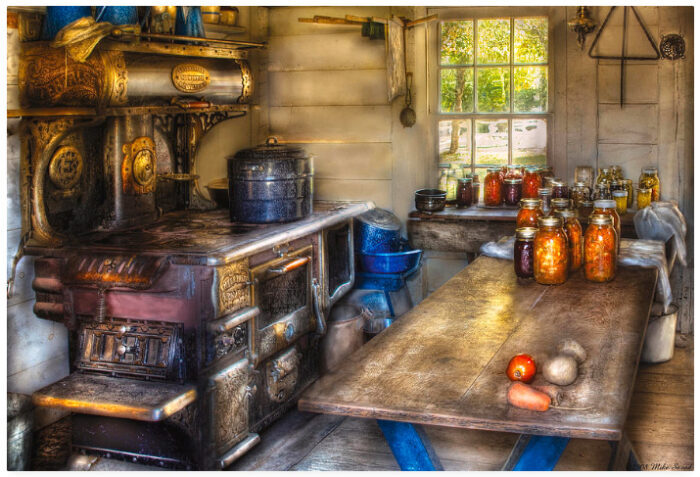

A jarring image of her early life, provided by Michael Savad again, showed me what it really meant to have no running water in the kitchen.

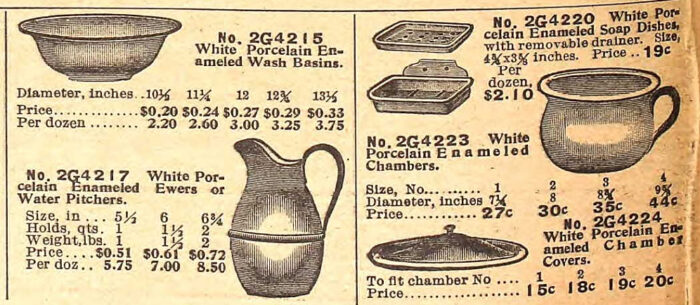

A ‘kitchen sink’ would actually have been a table or cabinet with raised sides, big enough to hold big basins, buckets, and bowls, as well as pans and pitchers. Containers came in an endless assortment of sizes and materials (tin, wood, earthenware) because jobs that required water came in an endless assortment. Buckets of water for cleaning would be carried in one at a time from the cistern or well outside. And since it had to clean the dishes, the house, the laundry, the people themselves, and then have to be hauled out again from bedrooms, house cleaning buckets, kitchen washpans and off the stove, it was used sparingly and often reused. Buckets of water for consumption and cooking were hauled up onto the stove or to a table under which another array of bowls and pans awaited for all manner of food collecting, preparation or cooking. The cabinet top usually had a hole in the bottom for any water that spilled into it and an empty bucket inside the lower cabinet to catch it. Sometimes a metal lining for the table top and sides, and the hole in the bottom, turned the table itself into a basin of sorts. I suppose lifting 40lb buckets of water up onto tables or the stove wouldn’t have been anything new to Tiwazzo. And just before moving to Lake Charles, she would have gotten used to carrying water up and down stairs from the few years they lived in a two-storey house in the little town of Parks a few miles down the Teche.

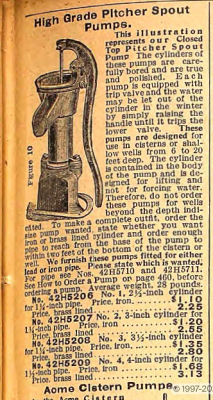

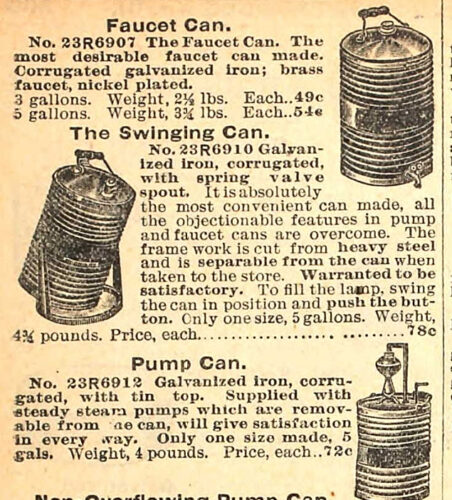

Other kitchen sink scenes of Savad’s gave me hope, though, that things might not have been so hard . . . that a basin cabinet could have had a pump jack mounted to one side, connected to a cistern through a pipe under the house. Sears showed me that pumps were indeed available in 1907 for cisterns as well as ground wells. Whether rental houses merited being equipped with kitchen water pumps, I don’t know.

~~~~~~~ kerosene ~~~~~~~

Savad’s kitchen sink scenes contained details, a candle sconce with a tin reflector backing here, a kerosene lamp there, which reminded me that Tisolay’s house wouldn’t have had electricity either. Electric lights, first suspended over Ryan St intersections, then fitted to a streetcar line and major business buildings, had only just started to spread to new construction for the wealthy, much like plumbing.

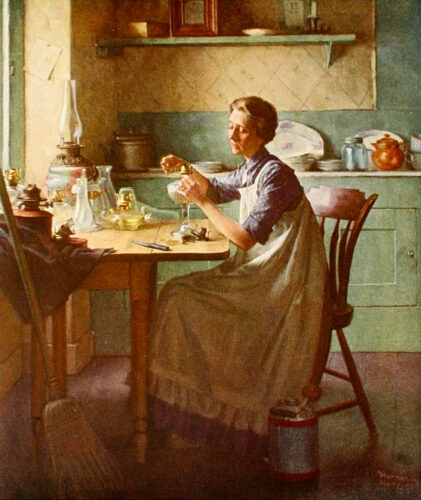

The idea of kerosene lamps gives me chills, and they must have been one of the more dangerous parts of everyday life. They did cast a wonderful glow over a room, though . . . table lamps, sconces, ceiling-mounted lamps, and the very dangerous hand-carried kind.

Norman Rockwell makes it look quite genteel, filling all the lamps in the house, and clipping or replacing their wicks. But there was nothing nice about cleaning the black soot from the inside of their glass chimneys, to say nothing of the air-borne soot that gradually settled on the curtains and rugs and furniture and whatever else.

A 5-gallon can of kerosene costs 50¢ ($15.75). If 1 lamp around a family table was lit for 4 hours a night (dad’s reading, mom’s sewing, kids are doing homework or playing a game), it would use about 3 quarts a month, and a 5 gallon can would last about 6 months.

~~~~~~~ ice ~~~~~~~

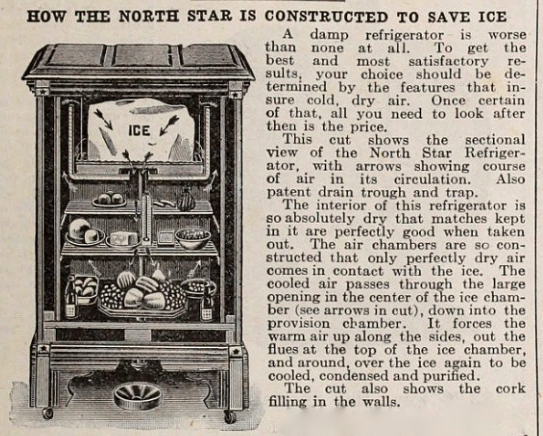

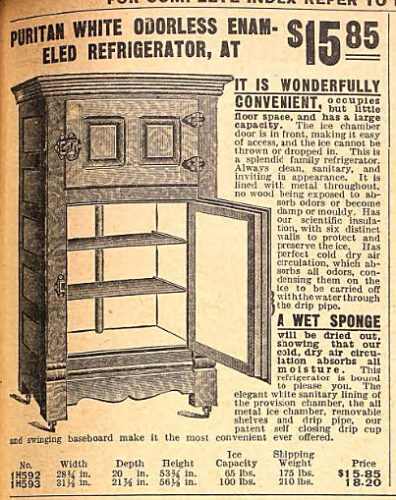

Ice was delivered every few days, usually in 50lb blocks which would’ve cost around 12¢ ($3.78) apiece, which would be about $1.44 ($45.36) a month. The delivery man would carry it into the house with tongs and heave it into the ice compartment of an ice box. Ice boxes were surprisingly expensive, more than those big cast iron stoves sometimes.

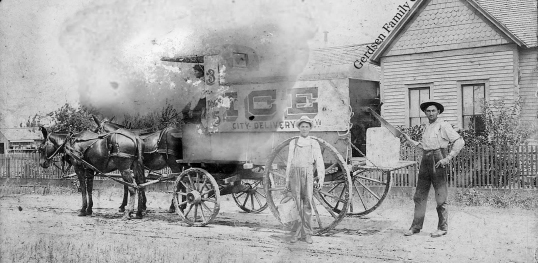

There is a photo of a Lake Charles ice delivery wagon in 1910 with a man and two boys. It is stamped as part of the Gerdsen Family Collection, and it’s possible it was a Gerdsen family business, or they were affiliated with the city’s ice company, which was owned by the Bird/Landry families that, unbeknownst to Carmen yet, she would marry into.

The Gerdsens, Danish/German Foehr Islanders brought to Lake Charles by Capt. Daniel Goos whom I’ve told you about, settled around St John’s Lutheran church a few blocks up Moss St from the Champagnes. (Tisolay’s neighborhood had once been informally called Germantown.) And since ice was generally delivered several times a week, the Champagne family might have known this man and the boys quite well, especially since they were the same ages as Presley and Roosevelt.

🎶After a day or so, the ice had melted enough through the little hole in the bottom that you could pull the pan out and drink it . . . so good and cold in the summers.”

Is that where you got your thing about ‘ice cold milk’?🎶

That happy chirp, “How would you like some ICE cold milk?”, was such a beloved part of my childhood soundtrack that even after I grew up, I never had the heart to tell her that when something is really ice cold, you can’t taste it. Like vanilla ice cream; if you let it get a little soft, the flavor of the vanilla really blooms. I’d eat milk in ice cubes, though, to have a recording of her asking me that oe more time.

🎶 “Oh, the ice cream. We’d sit on the back porch and crank and crank til our arms ached. So sweet. .. and yes, ICE cold.

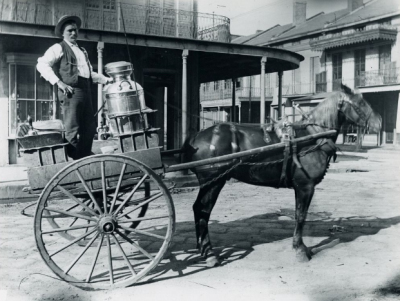

And milk was delivered too, but it was in big metal jugs that someone had come out to the wagon with a pitcher or bucket to get.”🎶

~~~~~~~ horse and buggy salesmen around the neighborhood ~~~~~~~

🎶“Coal was delivered to the house, too, in a big wagon that the man brought round the back of the house where he’d shovel it into the coal bin. Sometimes my Daddy would pick me up and we’d go outside to talk to the man, but he really just wanted to say hello to the horse. Farmers came from the country and drove through the neighborhood, too, with their fruits and vegetables early in the morning. People sometimes paid him with chickens and eggs in trade, so we sometimes got eggs from him, too.”

I have a hard time seeing gentle, ladylike Tiwazzo buying a live chicken, wringing its neck then chopping it off, plucking it, gutting it, etc, but that would’ve been the normal course of the day on the farm, would’t it. They didn’t have a butcher a block away.

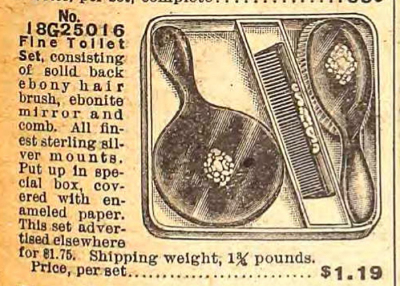

“All sorts of things came to the house in horses and wagons. It was all things you could get in town but that Mama said cost more in stores, like scissors, umbrellas, mirrors… hairpins and combs; everyone had long hair then. Sometimes it was magazines and books, paper and pencils. There was one man who brought sewing things, like buttons, needle and thread, ribbons, patterns, and fabrics… curtains and sheets if he had room. He always stayed and let you look all you wanted, and if you brought your scissors and kitchen knives out, he would sharpen them while you looked. Neighbors would come out, the women, and visit while they looked through patterns and fabrics together.

There was one with medicines… tonics, they called them.”

🎶“There was a man with cleaning things, soaps, brooms & brushes, mops and buckets and washtubs of every kind… and those rolling rug sweeper things.”

“There was a handyman who went around with all his tools and different supplies. Everyone had a song to call out what they were selling, and he sang out the things he knew how to fix. He always had screens because of the mosquitoes. He could sharpen things, too, but I liked the man with the ribbons and buttons.

We had a pie man, the Boohoo man. He didn’t have a horse, just walked around wearing an old top hat and long black coat someone gave him. Said when you ate one of his wife’s pies, you cried when there wasn’t any more.”🎶

Now what was so hard that Tisolay couldn’t just tell me little stories like that?

~~~~~~~~~~ bathing ~~~~~~~~~~

🎶I can think of 100 ways a conversation could’ve started. “Oh, that’s like the pretty flower pattern on the pitcher and bowl we had on our dresser.” Or some such. Anything. It would’ve just taken off, so easily. ~~~ “Oh, no, not for drinking, for bathing. There was a dresser across from the bed with a big pitcher and bowl, and we’d sponge off every morning with a wash rag from the bowl. Tiwazzo would bring up a pitcher of hot water every morning.” . . .🎶

🎶 “. . . We did everything there, fix our hair, brush our teeth… “(that certainly would’ve elicited a comment or two, the idea of brushing your teeth in the bedroom).🎶

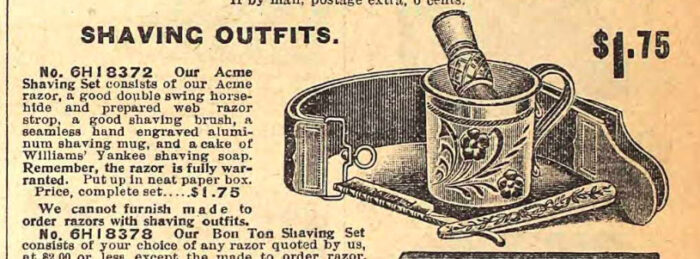

🎶“. . . And there was a mirror. Papa shaved in front of his.” ~~~ He didn’t shave in the sink? ~~~ “There was no sink; there was no bathroom. Only rich people had bathrooms.”🎶

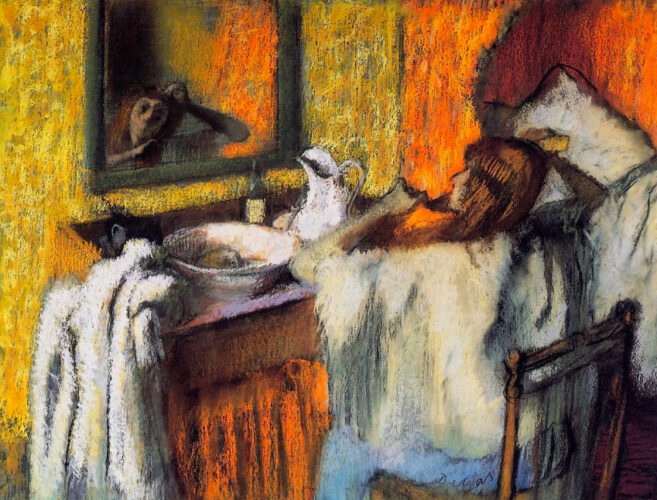

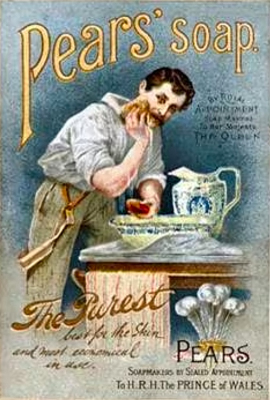

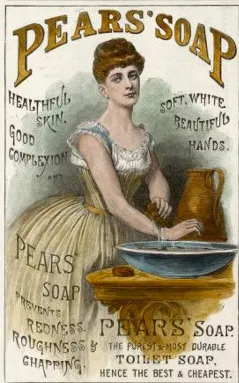

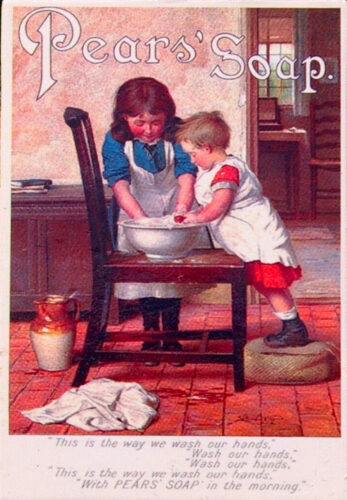

Pear’s Soap’s version of “Woman Taking a Bath“, with its Victorian taboo against nudity even in the bath, was a far cry from Degas’ more realistic (read: French) depiction. I wonder where 1907 Lake Charles fell on that continuum being on the far edge, but not really a part, of French Louisiana.

There was no such Victorian prudery on the other side of the pond; few European Impressionists could resist the beauty of a woman’s body at the bath.

Sears even taught you things with what they left out of their catalog, like how fast plumbing technology was changing America.

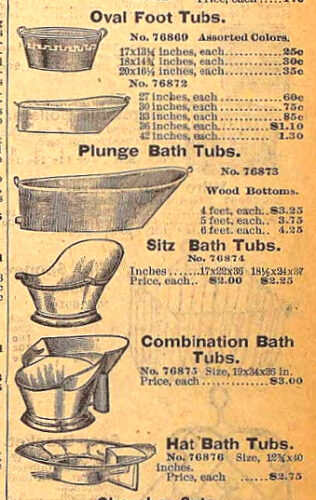

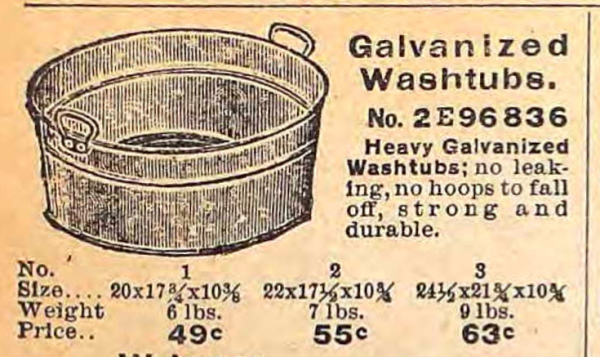

In 1898, all different kinds of portable tubs were available, with only one semi-fixed one that awkwardly folded up around its pipes like a Murphy bed. But by 1907, there were no portable tubs offered anymore, only the one whole-body ‘Plunge’ tub, and the rest were for plumbed bathrooms, clawfoot tubs, etc. Only the all-purpose round washtub remained, the kind you can still get today.

🎶Who bathed you? Did Tiwazzo? Beulah?

Did you ‘graduate’ from being in your parents’ room as a toddler, maybe being bathed in their tub, to living in your sisters’ room, where I presume bathing duties periodically fell on them? You never talked about Beulah, and it seemed like you two didn’t spend much time together. She was 16 when you were 2, so maybe her mind was too steeped in the world of boys, or more serious things, to really get to know her baby sister.

Carmen was 13, though, and we already know how close you two were. Did she bathe you?

🎶My favorite Pear’s ad makes me imagine Carmen, as you grew up, putting the bowl down where you could reach it and teaching you how to bathe yourself, .🎶

When your hair started getting really long, after Beulah graduated and became a working girl, was it Carmen who brushed your hair and got you ready for school?🎶

~~~~~~~~~~ (aside) ~~~~~~~~~~

Tisolay loved Pear’s, so I grew up with it. She had it in her twinkly silver and crystal bathroom, along with her 2 Dresden figurines, and it looked like a giant amber jewel, completely clear. I remember holding the soap up to my eye and looking at her through it?

Those figurines were all still there 40 years later when she died, albeit a good bit worse for wear, covered with decades-old rings of yellowed scotch tape she would put around the arms and one of the necks when they got knocked over. She fixed everything with scotch tape. I don’t know how I was never one of the ones who broke one, because Tisolay would lay me down across the vanity with my head hanging back into the sink and wash my hair, with all those delicate breakable things maybe pushed a few inches back against the wall, nothing more. Who knows, maybe I was. She would never have told me so, though . . . just stuck a piece of tape around it.

Pear’s soap and Dial shampoo in the triangular orange bottle; I’d know both those smells anywhere.

If you stood in front of the sink, you saw the back of your head reflected from the medicine cabinet mirror behind you, but if you opened the medicine cabinet door just a bit, a magic portal opened up in the mirror in front of you with the front of your head, then the back, then the front, on and on, through a twinkly pink and silver wormhole that curved off into infinity.

A year after she died, Hurricane Katrina hit, and repairs ripped that mirrored wall out. I didn’t know that I would never live in that house again.

~~~~~~~~~~ Cisterns, outhouses, and bathing in the kitchen~~~~~~~~~~

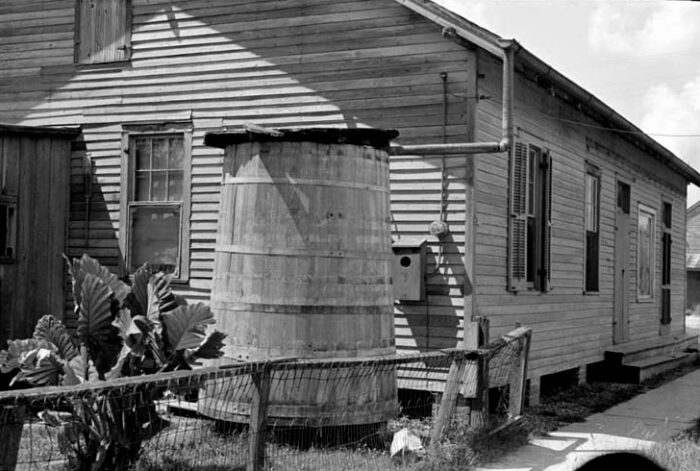

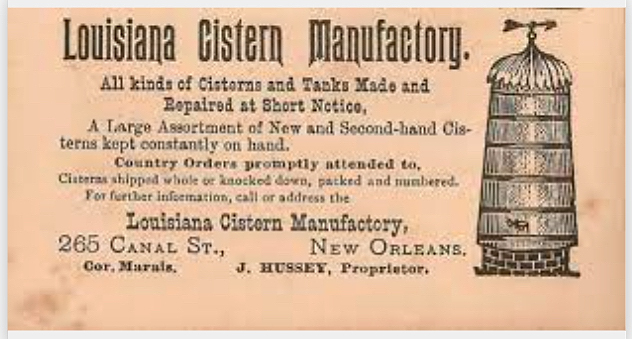

🎶 Anyway, back to the conversation we could’a had, but didn’t 🤨, about there being no water in the house. “That’s right. All through grade school, our water came from a cistern outside the back door. Mama had to… ” Yep… I’d’a stopped you right there. I loved cisterns, and you knew that. “Wait a minute. You had a cistern? Remember that day when I came back from meeting Yola with the shots of Adeo’s house [Ti’s grandfather], and the one with Geraldine in the back yard with the cistern off the back steps?.. the one where she’s holding the kitten up to her face? Now, what would have been so bad about telling me about the cistern at your house? ~~~🎶— No, you didn’t know them. Yola was Adeo’s baby sister’s grandchild, your 2nd cousin several years younger than you. She went to live with Tante Sin and Adrien after Adeo died when she was in her early teens . . . something about trouble with her new step-mother. Never left, brought her husband to live there, had Geraldine… they stayed until Tante Sin died in 1962.🎶

I did love cisterns, the raised, wood-barrel kind on a round brick base, connected to the roof by a gutter, usually right off the kitchen door. A few old houses in the historic districts in New Orleans still have theirs, though they aren’t used anymore. I found the circular brick base of one under about a foot of dirt in the yard of my old Victorian on Magazine St when I was digging to find out why the yard wouldn’t drain after a rain.

Ruins of old Acadian houses I used to see up and down Bayou Teche often still had the remains of theirs. That was back in the 80s, though; they’re gone now.

🎶 I may know who built your cistern, and his shop is on the Sanborn maps through 1898. He was one of only 2 in 1895, a few years after 617 was built, and had been in that shop for at least 15 years. When you were a girl, everybody but the rich still had cisterns, though not many were being built anymore. You would’ve been running in and out of Karl’s and Bernard’s houses all the time, and they were all well-off or outright rich. That picture of you over at the Bel mansion on the corner, for Della’s birthday party?.. Jeez, that house must have seemed like a castle to you.🎶

Was she uncomfortable when they came to her house? I really don’t see embarrassment over something like not having plumbing and electricity causing her to never speak of her childhood. I understand that something very sad was a part of her home life, that she was the target of a bully in her own home, and I ache for her. And I know she had a good reason for not wanting to talk about it. It’s not that I don’t respect that, at least I hope I’m not disrespecting it. But she threw all the good out with the bad, and the majority of it was good. And it killed me that she was ashamed of her life and of being Cajun, with their hard-won heritage and the incredible, ‘what-are-the-odds’ resurrection of their culture in Louisiana.

🎶Hell, Ti, I left my job and my field, went back to school, went all the way to Nova Scotia, found your 11-x-gr-grandfather’s house cellar site, took a filler stone out from between two boulders at the bottom of the cellar, the layer I know he would have laid with his own hands back in the 1670s, and I put it into your hand. ‘Thou shalt not be ashamed of who you are. You are a work of art’. Besides, I was always able to make you laugh about things, and give you a different perspective. Even there at the end, when you were so scared, forgetting who people were. We had some pretty hysterical laughs, right up to the end. And… it’s just… I can hear your voice, how you’d sound having fun with it, … messing with me with that wide-eyed deadpan look, holding it as long as you could before cracking up.

“We did take baths, you know… (wait for it)… on Saturdays in a big washtub downstairs in front of the stove; the girls first, while it was still clean”. Oh, ewww!🤣 “It wasn’t so nice by the time it was Roosevelt’s turn.” And you’d watch my face as I got more and more weirded out. “Of course we had clothes on. We wore a bathing gown, light and loose.🎶

J Euclide and Tiwazzo probably had a small tub of their own in their room, for a little privacy. I wonder if Tiwazzo helped bathe J Euclide like the French miner’s wife.

🎶“Upstairs, at the dresser, we just bathed under our nightgowns. The bowl and pitcher were part of a set. There was a soap dish and a mug for our toothbrushes, all with the same flower pattern.” Oh, you’d have had real fun delivering the coup-de-grâce).

“Even the chamber pot, except we kept that under the bed.” ~~?!~~ “Well, of course! You don’t think we went out barefoot to the outhouse in the pitch black and rain, do you? And the next morning, you’d take it to the outhouse and empty it.”

Oh yeah, right, YOU brought it out … little miss baby-of-the-family, apple-of-everyone’s-eye, don’t-know-what-a-can-of-Comet-is!🤣🎶

Man, I just can’t wrap my head around Tisolay going to an outhouse as a regular part of her life. I gotta say, I love the little child’s seat. And I guess we know where one of the most likely places to find a Sears catalog was… albeit not in its complete form.

~~~~~~~ laundry ~~~~~~~

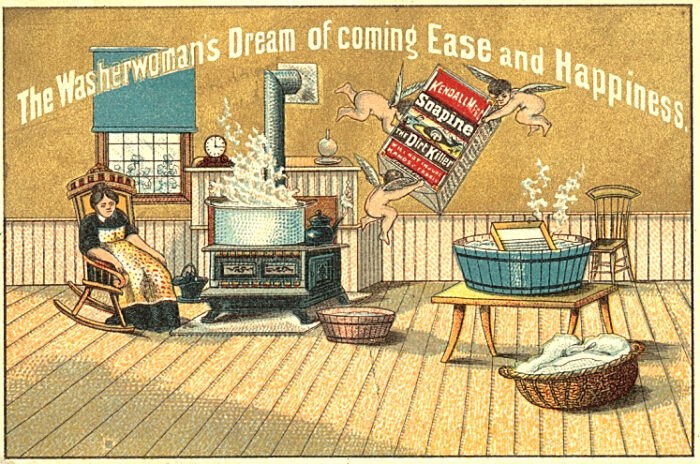

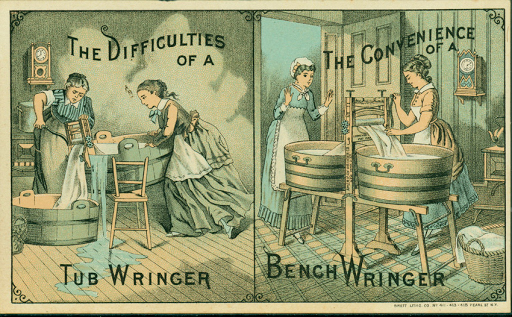

Of all the labor involved with doing everything by hand and from scratch, everything I’ve read says that laundry was the most hated part of turn-of-the-century housekeeping. Without electricity for the washing machines, water heaters and irons we know today, everything about laundry was a nightmare. And it involved the stove as well. In fact, it monopolized the stove for most of the day, and some followed a tradition of doing weekly laundry on Mondays because the Sunday dinner could usually be stretched to provide Monday night’s as well. Clothes that had been set to soak the night before, then boiled that morning, would be lifted from the scalding water with a stick or tongs into the tub, where a washboard awaited, or a machine. How often did things fall on the greasy floor in front of the stove? How often did they plop back into the pot, splashing scalding water over Tiwazzo;s hands? Grueling work, and the clothes haven’t even touched soap yet.

The question is… did Tiwazzo stick with the old ways and scrub with lye soap that did God-knows-what to her hands? Or did she have a machine? Whether she did or not, I’m gonna assume she had a wringer (they called them mangles?) which could fit either washtub or machine. And I’m also gonna assume that she had a laundry boiling pot on her stove, a large oval pot that fit over a front and rear burner.

Surprisingly, or maybe not so much, I found no evidence that Degas, Mary Cassatt, Toulouse-Lautrec, or Picasso were ever inspired by the beauty of a woman heaving heavy dripping blobs of scalding wet clothes out of a boiling pot on the stove with a stick. There were no vintage photos either. But there were trading cards.

Some of these cards show a housekeeper working together with the lady of the house. I don’t know if the Champagnes had a housekeeper of any kind when they were in their first house, still by themselves. But these cards make me wonder if the woman Tisolay remembers as a cook actually did the whole housekeeping thing, including helping Tiwazzo with the laundry. It also makes me wonder about the dynamic between the sisters, since Mathilde was 11 years younger than Tiwazzo. Did she provide the second set of hands that made the job easier, or did she fall back on her role as baby of the family?

The only realistic image that gave me a hint of what a laundry day might have looked like in the Champagne household wasn’t of a laundry day at all, but of a canning day. Or rather the day after, after the mess had been cleaned up and everything put away except the shiny colorful jars of goodies spread across the tabletops.

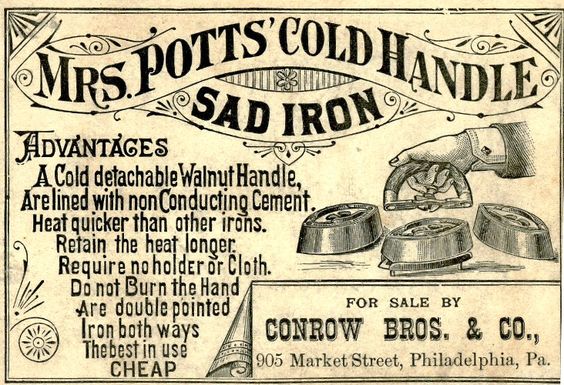

There’s a large pot on the stove which had probably been used to steam-seal the jars, but it could do double duty as a laundry boiler if a larger oval pot, the kind that sat on two burners, wasn’t needed. Like if Beulah found out on Friday that a favorite dress that’s dirty is needed for a Saturday night date, and laundry isn’t done til Monday. Toward that end, the fan-style drying rack high up on the wall above the pots in the corner would come in handy for that favorite dress if it were raining outside. In south Louisiana, even on a sunny day, summer humidity in the 90s could have prevented it from drying fast enough, and left it smelling moldy when it did. And I guess Beulah would’ve had to crank up the sad iron that’s barely recognizable, on the upper shelf above the stove’s warming closet.

I can imagine how this kitchen would look laid out for laundry day, with two big washtubs on the table for soapy water and clean rinse water, and a wringer on the end of each one. Maybe a basket after that to receive the wrung-out clothes, and at the foot of the table, a self-standing radial-arm drying rack. Actually, in the photo, under the pile of big pots in the corner, there’s something that looks like a bench wringer, so maybe the table was pushed back and the bench wringer, set up alongside the stove, was what held the two tubs. Tiwazzo would’ve had a clothes line outside, but she may have hung a line up in the kitchen as well on laundry days, where the stove would solve both the rain and humidity problems. Maybe the table was where the ironing was done.

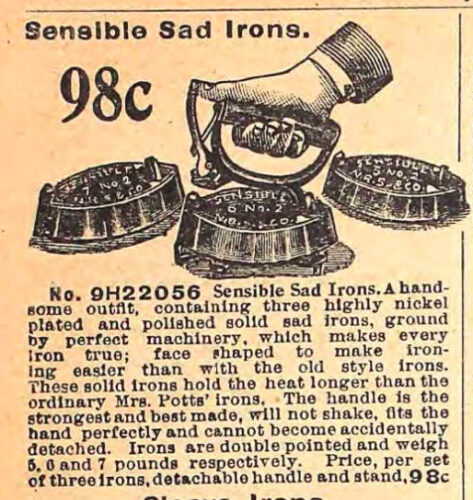

“Sad” irons were solid iron and heavy (sad being archaic English for solid), and had to be heated on the stove. They were sold 3 to a set and used all at once, rotated as they cooled. Many had a single interchangeable handle that didn’t get as hot as the solid-cast model.

There were small pot-bellied stoves made especially for boiling laundry in big wash basins, whose “belly”, rather than being round, was multi-sided with flat facets that each held an iron up against it. These were most likely for larger use than the single family, perhaps a hotel or boarding house, or a laundry business.

~~~~~~~ laundry and the psychology of class distinction (*who knew!*) ~~~~~~~

🎶No, Tisolay, you know what? What if the real question isn’t so much whether Tiwazzo had a washing machine to do the laundry or not, as whether she did her own laundry at all. I’ve always been puzzled by you saying that Tiwazzo didn’t cook and never taught you how to cook… that you grew up having a black woman for a cook. Weird, partly because Cajun French women, and men for that matter, were famous for their cooking, but mostly because you always said that there was never any money for anything but the necessities. Yet, there was enough to pay a cook. Which leads to the question, would Tisolay give the job of cooking to someone else, but keep the far-more-obnoxious job of laundry? 🎶

It led to a lot of questions, actually. Was Tisolay using the word ‘cook’ euphemistically, because after 8 decades, she’d finally learned the current political incorrectness of the word ‘maid’? I don’t think so. But they surely didn’t have two separate women doing the cooking and the cleaning/laundry. The real question, though, was why hiring a cook was not in the same category as other luxuries you said your family couldn’t afford. Why did Tiwazzo and Mathilde think that regardless of how meager J Euclide’s salary may have been, and the fact that there were 2 ‘women of the house’ who could’ve split the dutieswork, hiring a cook was still a necessity, not a luxury? Then I thought about Tiwazzo and Mathilde’s childhood back on the farm and what their mother Ada would’ve been like, being the baby of 22 children in a well-to-do, slave-owning family. She would’ve been taught how to cook, but she’d have had a cook whom she taught how to cook. And she’d have taught her girls, expecting them to teach their own cooks how to cook. Ada got married right after the war was over. How did she raise her girls? Maybe I needed to look at what little I knew in a new light, maybe take the ramifications of the Civil War and the farm’s loss of their labor pool more into account than I had been. I knew that it decimated Louisiana’s farm economy, but that was 40 years before. Louisiana had recovered. What was I not seeing? Okay, bear with me here.

🎶Ti, you remember the picture of Adeo’s house up by the road, how plain it was? I was so excited when Yola gave me a picture of your grandfather’s house, the house you remembered visiting so vividly when you were 5. But I was a little disappointed, too, that it wasn’t one of those classic old Acadian houses, with the staircase on the front porch going up through the ceiling into the steep overhung attic that was the boys’ garçonniere, and the porch wall with its whitewashed bousillage between the beams.🎶

Yeah, I seriously freaked when I went to the Acadian Village outdoor museum and saw that one of their restored houses was Ada’s uncle Narcisse Thibodeaux’s house, built in 1820 when he got married. (He was Adeo’s great uncle, as Ada’s mother was his aunt.).

Then there was Tidouce’s house next door to Adeo which had been built by her grandfather Omér, Ada’s older brother, in 1851 before the war. Tidouce’s daughter Verna was the cousin that Tisolay told me to look up when I first visited Cajun Country and didn’t know anybody. Verna brought me to Tidouce’s house that first week because they were packing it up to sell, right after Tidouce died, but it was at night and I never got a picture of it. Then it was gone, bought by someone who moved it to another parish and restored it. But I remember it.

I remember the tiny, dangerously steep staircase in the livingroom, almost like a ladder going up to the attic, which must have been the staircase from the front porch. Maybe the garçonnière stairs came inside when Tidouce’s parents realized she would be their only child and there’d be no need for a separate boys’ quarters with its own entrance. Verna had been an only child as well, so it was never needed outside again. I also remember the thin black threads of 130-year-old moss sticking out of the livingroom walls all along the door frame where the bousillage had crumbled away, taking the wallpaper with it and dropping grit all down the arm of the sofa. So many layers of wallpaper? And I thought it was a riot that the top layer was like this psychedelic 1960s Peter Max design, big orange flowers. I can’t imagine Tidouce sitting still for that, even if she were as true to her name as everyone said. (Tidouce means little sweet one.)

Anyway, Adeo didn’t build a traditional Acadian house for Ada, and I’ve always wondered why. It took me years to put various facts together surrounding not just the family history but the history of St Martin parish. Turns out getting married on January 14, 1869, right after the Civil War, was only the start of it. A Yellow Fever epidemic 2 years before had swept through the family, particularly his uncles who would’ve communally helped build his traditional Acadian house. They were also the men who’d been farming the land that supported the family while the young ones were off at war. Adeo returned 2 years later to a farm that no one was farming and a family that had lost its income and labor pool, both black and white. Soldiers from the Mississippi River Valley above New Orleans were returning to find their former slaves gone to more racially hospitable parts of the country or trying to carve out a niche of their own in the new Reconstructed Louisiana, but Adeo returned from the war to find many of his grandfather’s former slaves still on the land, nowhere to go and no way to go there. St Martin Parish, the oldest French enclave west of the forbidding Atchafalaya Basin, had much less contact with the English language, and the slave population even less so, and when they were freed, they were not only cut off from the housing, food, clothing and health care they’d once gotten from Adeo’s family, but also the language skills that would’ve enabled them to go elsewhere. So they stayed as Adeo’s share croppers, working the same fields they always had and paying rent for the cabins they’d always lived in, on the far west edge of the Thibodeaux property where the cane fields begin to sink into the swamps around Lake Martin. Signs of where their homes were, over 150 years ago, are still visible in the vegetation growth patterns.

Adeo may not have had the money to build what he could have before the war, but he had a population of sharecroppers to work the land. And because of the mass family death in 1867 necessitated a repartitioning of his grandfather’s estate, I suspect the few surviving heirs made a little bit of money from the sale of the land that had belonged to the many unmarried aunts and uncles who had no heirs, which his father eventually bought for the sons of his second marriage, Adeo’s half brothers. The wives and daughters of the newly-freed Black Creole families were desperate to earn what pennies they could for their families and took what work they could cleaning houses and cooking for nearby white families, as they had before, at rates far lower than they could’ve gotten had they left. Did Ada, the baby of a huge family, know how to do the hard work of keeping a house? Did she teach her girls to keep house? Or did Adeo pay someone pennies on the dollar to keep his house? Did Alicia (Tiwazzo) and Mathilde grow up amidst what was, in essence, a similar version of the social structure that existed before the war, keeping the women of the Black Creole families in the servant class?

🎶Whatever the reason, your granddaddy Adeo didn’t build your grandmother an Acadian style home like the ones they’d grown up in, but he did enlarge it with a side extension which I’d imagine is where your family stayed when you went back to visit in the summer of 1910, since Adeo, Tante Sin, and Adrien were all still there.

You had some pretty great memories of that house, considering you were only 5 the last time you visited. I love that you remembered him as Yépope, which I assume Beulah and Carmen, his first grandchildren, named him, a corruption of vieux papa, “old” papa, as opposed to J Euclide, who was just plain papa. You remembered the big oak down by the water that I’d study under 70 years later, and the long tire swing in the pecan tree next to the house up by the road that swung you so far out. You even remembered the two cedars that Tante Sin planted on either side of the front steps 5 years before, little scrawny things she’d planted when she married Adeo. They became lush beauties in the 1964 shot, and then served as markers for me in the 80s when they were the only things in a solid field of swaying red grass to indicate that a house, barns, a cistern and water pump, countless little out buildings and sheds, animal pens and coops, and a family had once lived there. Mostly, though, you remembered the train that passed behind the house, right before the cane fields started, and how it passed so slowly that the conductor was able to say hi to everybody as he tossed their newspapers into their back yards. You remembered running out the back door for miles, through grass twice as tall as you to meet the train, when you heard the conductor blow his whistle way far away to signal that he would soon be there.🎶

She didn’t believe me when I told her that the yard, though big by city standards, was just a regular-sized, fenced-in yard, and the railroad tracks were right there at the back of it, just a minute’s stroll from the back door. “They must have moved the tracks!”. 🤣 Yep, memories of a 5-yr-old who’s only 3½ feet tall.

🎶Wait… You were 5… that trip was in June of 1910… dear God, that was 6 weeks after Lake Charles’ terrible fire!! Oh, wow, Tisolay, was that what that visit was about? Was the reason you remembered it so well because you stayed there for longer than you remembered?..like the whole summer? The following year, the 1911 directory showed that y’all were no longer in the spacious 2-story house at 511 Moss St., but had moved a few doors around the corner to a tiny cramped cottage that your mom & dad would never have moved a family of 7 into if there’d been another option. I’ll bet your landlord needed the house, maybe because he’d lost his own home, or maybe because he was raising the rent to what a wealthy, suddenly-homeless family would be able to pay. I’ll bet you anything your Daddy sent y’all back to Breaux Bridge to stay with your grandfather because he was looking for another place from that impossibly small house on Mill St.🎶

I imagine Lake Charles was something like New Orleans after Katrina… businesses and stores destroyed, the town lawless, and armed looters roaming the wealthy neighborhoods around the town center where grand homes, though unlivable, were still full of expensive things. The town center itself; City Hall, the Courthouse and all their records, the main Catholic church and school, and ironically, the fire department, was dust in the wind, flat land blocks of wood ash and twisted pipes, the occasional chimney or cistern standing alone. There weren’t enough policemen to control the disarray, and hundreds of panic-stricken homeless people had lost everything they owned, many of them wealthy, some no longer so, but most of them ill-equipped for homelessness and life without servants.

Is that what happened with Tiwazzo and Mathilde? Helpless women who’d always had servants and never learned how to cook or clean? Or was it not so much an inability as a conscious choice not to do housework, to hire someone else to do it, the last vestige of their status as descendants of one of the founding Acadian families who became one of the wealthiest landowners in St Martin Parish, and the only way left to them to claim the dignity of what their ancestors had once been.

🎶Back in the 1980s, when I was just starting to cook myself and collecting cookbooks from places Mother and I had traveled to, I told you about this new interest, as I did everything else. I’m not sure how much I noticed at the time, but looking back, I remember a certain silence about my cooking where you were usually excited about anything that excited me. I had no experience with disapproval from you, so I may not have recognized that that’s what your silence was covering up. I teased you for being out-of-step, thinking that cooking was something a servant did, not a hobby for someone above a certain class and education level. And I knew you loved being the wife of a well-to-do banker high up the social ladder of New Orleans society. But it never occurred to me that there were deeper historical roots over many generations behind what I thought was silly snobbery, and that it might not be so much an expression of status and wealth as the shame at having lost it.

Is this why Tiwazzo didn’t cook? You always spoke of her as so delicate and genteel. Was this ‘code’?… that she was a lady, and ladies didn’t cook or do laundry?🎶

Wow. None of this negates the picture I’ve been building in my head of what my grandmother’s home might have looked like, how it was furnished, which technologies informed her childhood lifestyle, etc. But when I started a chapter about finding my grandmother in a 1907 Sears catalog, little did I know that it would end with a real shift in my own mindset regarding the division of labor in Tisolay’s home, the socio-economic effects of the Civil War in my own family, and the psychology of perceived class stratification. Hmmm, building wild hypotheticals and theories about people based on nothing more than a few sparse facts, filling in the rest with correlations and circumstantial evidence regardless of accuracy, has nonetheless furthered my concept of my grandmother’s childhood. But is it right to hit the ‘publish’ button and put it out there? I could be completely wrong, and I hope the spirits of my ancestors don’t visit me in the night and kick my ass, which I could well deserve.

On that note, I’m shutting this one down.

~~~~~~~ cont’d on next post ~~~~~~~

================================================================================

[for my own organization – 58.5 screen pgs, moving, unpacking – 511 Moss – 1907 Sears catalog, 2 . . . stoves, 15.5 . . . kitchen cabinets and contents , 3 . . . moving(cont’d), shipping, furnished vs unfurnished? – the light dawns – no running water, 5 . . . kerosene – ice, 6.5 . . . horse and buggy salesmen, 3.5 . . . bathing – cisterns, outhouses & bathing in the kitchen, 11.5 . . . laundry, 7 . . . laundry and the psychology of class distinction (*who knew!*), 4.5