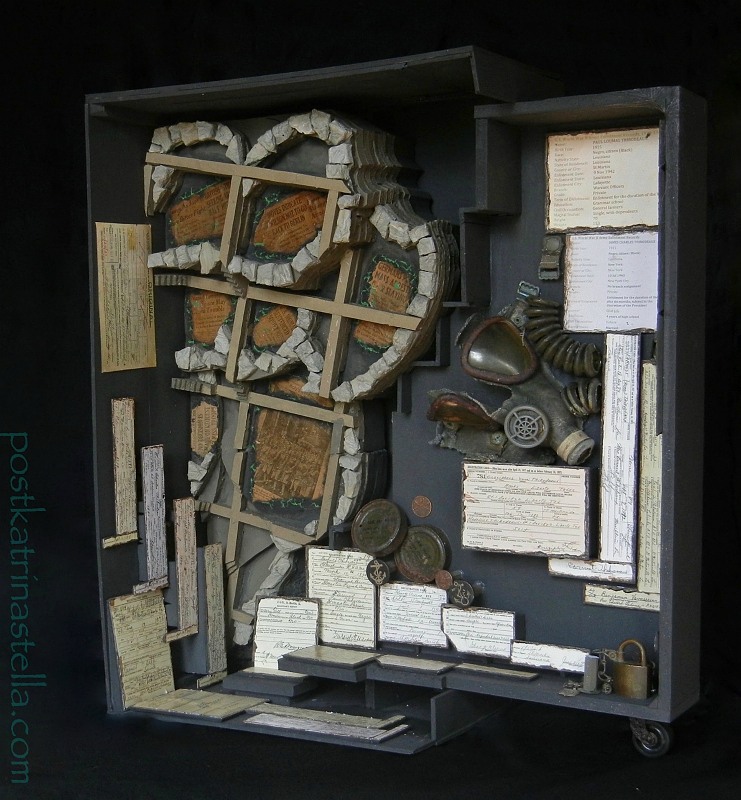

- Backdrop – ice box door

- Left side – porch column from back verandah, two pieces

- ….. – iron wire clothes line, remains in situ, attached to column

- ….. – curtain fragment from front bay window on clothes line

- ….. – painted silhouette of column and bracket, before decay

- Upper right – (outside of container) barrel hoop

- ….. – wall and corner, mirror image of column and bracket contours.

- ….. – painted silhouette of bracket above the front bay window

- ….. – window screen from bay window

- [Lower right – Diy-Gid-Biy 1 excavation in northern Cameroon, explained in its own post.

—————————————————————————

(You’ve come in at the middle of a complex and wonderful story. To start from the beginning, go to https://postkatrinastella.com/thelesphore-a-family-hero-in-post-civil-war-cajun-country-pg-1/)

—————————————————————————

Ice Box Door: The rusted-out door of an ice box was in a half-collapsed shed in back of Thelesphore’s house beneath a tangle of things, all broken or rotted, that included a rusted-out iron headboard, a plow shaft and blade, half of a wooden rocking chair, several iron cauldrons and porcelain wash basins, and a crosscut saw.

The family remembers, back in the 1940s when they were kids, sliding the drip tray out from the bottom on hot summer days and drinking the cold clear water that dripped down from the block of ice on the metal rack above. A set of ice tongs, rusted shut, was one of many small things buried by decades of leaf litter. One of its two points, meant to grasp 40lb blocks of ice, was still intact.

Left – Right rear corner of shed behind Thelesphore’s house

Front Verandah, Eastlake brackets: Thelesphore Thibodeaux was a Black Creole French farmer, the son of a white Acadian sugar cane farmer and the ex-slave woman he raised 8 children with after the Civil War and finally married on his deathbed at age 70. He was an intelligent and responsible man respected by his mother and siblings to act as head of the family after their father died. A hotly-contested, hard-won inheritance that saved his family’s home and livelihood in 1895 allowed him to build this fine little house whose character is defined by the Eastlake bay window, with its gingerbread brackets.

To read about the family circumstances surrounding its construction, go to The Thélèsphore Thibodeaux house, St. Martin Parish, Louisiana.

Back Verandah Column: A badly decayed cypress column in several segments was found collapsed and rotting in the ground beneath the scattered sheets of corrugated tin roofing that had collapsed on top of it.

Originally, the absence of stairs leading to any of the back doors was a mystery to me, until the family began to tell me stories of them playing on a long open verandah at the back of Uncle Bro’s house (what they called their great-uncle Thelesphore) that ran the length of the house from the central vestibule all the way back to the kitchen.

On closer scrutiny, I saw many signs pointing to the existence of a verandah. The ghost of its roof could be seen in the outline of missing weatherboards, and the stubs of a few floor joists still jutted out from the sills. And it turned out that what I thought was a precarious-looking pile of rubbish on the ground, jagged edges of rusty metal peaking out from beneath a blanket of fallen leaves, was actually a layer of corrugated tin roofing resting on the remains of the brick piers, twisted further upwards by weeds long since grown into trees.

Far from being the expected rubbish heap, once the metal sheets had been cleared, the only thing beneath them was a mushy fill of woody pulp that I can only guess had once been the verandah’s beams, planks and, true to the quantity of it, the wide steps that the family described as running the full length of the verandah. I did find a large, broken piece of a grooved grindstone, but it seemed intentionally placed at the base of the leaning cistern, perhaps to bolster a sinking pier.

The family remembers those steps being a social hub when they were children, all cousins within a close-knit family compound of neighboring households. Only the oldest remembers Thelesphore, but they all knew his youngest son Leonard, their daddy T-Boy’s 1st cousin, who had brought his wife to live in the family home so he could care for his aging parents. Leonard and T-Boy’s children grew up together as best friends. They made ice cream on hot summer days, sitting on the steps turning the crank, and I found the cranks and paddle blades to prove it, several sets. The girls played with paper dolls on the long verandah steps while the boys played ball in the side yard. And they remember the boys next door, their forlorn faces, hanging on the fence wishing they could join in the ball game. They were cousins, too, grandsons of Paul Hypolite, Thelesphore’s younger brother, just as my Thibodeaux trio telling me their story were grandchildren of Louise, Thelesphore’s baby sister. But Paul, who had taken his grandsons in when their mother died, was a stern taskmaster who disapproved of children wasting time on leisure games when there was always so much work to do on the farm. Ironically, it was in one of Paul Hypolite’s old sheds that I found a very rotted baseball bat, as well as a softball whose stuffing had been removed to somebody’s nest a few feet away. (To read about Thelesphore, Paul and Louise’s parents, the white planter and ex-slave girl whose family of 8 are at the heart of the Thibodeaux story, go to Thibodeaux/Azor Succession #2859, 1890s Breaux Bridge, La. )

After Thelesphore and his wife died within 5 months of each other, Leonard and his family moved out of the house and his oldest brother Caffrey moved in. The family today remembers Caffrey’s wife Anna sitting on the chair she kept in the doorway between the kitchen and the verandah.

They remember her at her washtub, which hung from a peg on the outside wall by the cistern, the washtub that did double duty, cleaning laundry by day and them by night in front of the fire when they slept over. She did laundry this way until the children were long grown, since Caffrey didn’t have electricity installed in the house until the mid-1960s.

When Caffrey bought Anna an electric wringer washer on wheels, they remember her wheeling it out to the cistern on washday, then wringing everything out to hang on the wire clothes line that was stretched between two columns, a piece of which still remains on the column segment in the sculpture box. She did laundry like this, using water from the cistern, until she died in 1972, because Caffrey never did have plumbing put in. The house has no bathroom, no running water.

More than anything, though, the family remembers the wonderful smells that wafted over the steps from Anna’s kitchen, and the big cast iron stove her previous employer had given her as a wedding present back in the ’30s. Anna was well-known for her cooking, as was her sister Una, next door, the mother to my Thibodeaux trio. Cousins T-Boy and Caffrey married sisters, and the whole neighborhood, as well as friends who ‘just happened to drop by’ at dinner time, reaped the benefits of it.

No one remembers when the big iron stove was taken out of Anna’s tiny kitchen, or whether it was before the electrical stove was put in or not. But I found one of its beautiful doors buried beneath the trash pile next to the back shed, and it had a piece broken out of it which may give some indication as to why it was replaced. Was this what led Caffrey to modernize to electricity, because Anna needed to buy a new stove, which were all electric by then? He doesn’t seem to have liked the idea of modernizing, given how willing he was to continue to use the outhouse behind the house all the way into the 1970s, and bathe from a basin filled from the cistern.

In any case, even with electricity, air-conditioning was never one of the modernizations, so it is easy to imagine the back verandah of the house being the place where much of life happened, work and play.

Sculpture process: ————————-

_________________________________________ Next up, “War” ________________________________________