When a Texas researcher contacted me in July of 2014 about an 1894 succession transcript she’d seen my gr-gr-grandfather’s name in, the succession of a white sugar cane planter named Onezime Thibodeaux that legally recognized his deathbed marriage to Elizabeth Locus, a former slave woman, and legitimized the rights of their 8 children as heirs to his sugar cane farm on Bayou Teche, deep in Cajun French Louisiana, she also gave me the address of another researcher she said might also have useful information. He was a descendant of this marriage, as was she, who had written a blurb on the succession and called Thelesphore, the 2nd oldest of the 8 children, the family hero for convincing his dying father to legally finalize a marriage to his mother from his deathbed to save the family. He rode into town to get the priest who not only performed the ceremony there at the old man’s bedside, but when validity of the marriage and succession was contested by the white planter’s sister, testified strongly to its authenticity in court. This researcher, whose name was Donald Thibodeaux, had read my “Breaux Bridge” blogs about my grandmother, her French Cajun Louisiana roots, and the farm that had been in the family since 1763, which is when the British took over the French colony of Acadie and my ancestors, released from Halifax prison, and, knowing their homes had been burned to the ground by the British, set sail for the Catholic colony of Louisiana. Don told me that he was from Breaux Bridge and had recognized every facet of the maps that I had drawn of the property. He told me, though, that the person I should really be talking to for memories was his oldest sister Sylvia who was right here by me in New Orleans, a 78-yr-old nun with the Sisters of the Holy Family, an African-American order whose 180-year history is all bound up with that of the unique mixed-race Creole culture of 1700s and 1800s New Orleans. When I emailed her, she told me she lived only 5 minutes from me, was recently retired, and was, yes, keenly interested in working with me to bring the family story to light!

Turns out, she and her brother Donald grew up on the lane that divided their family’s land from my family’s. They were grandchildren of Thélèsphore’s baby sister Louisa, the 7th of Onezime and Elizabeth’s 8 children. Don and another sister, Josie, still lived on the land, across from each other on the road that ran alongside the bayou, 100 ft from the two cedar trees that had once flanked the front steps of my gr-gr-grandfather’s house. My grandmother remembered being 5 yrs old in 1910 when she last saw her grandfather and his house, which she remembered most for the train that passed slowly behind the back yard every day, where the barn and sheds and animal pens of domestic farm work gave way to the endless rows of sugar cane. Its whistle could be heard long before it arrived, creeping slowly down the bayou through everyone’s yards so people had time to come out and get their newspaper from the conductor who would toss it to them from his window, no doubt with a friendly wave, and maybe a “how’s the family?”. (Only 16 years before, her grandfather Adeo had been, I’m sorry to say, the next door neighbor referred to in Onezime Thibodeaux’s succession trial as being against the validity of the marriage, and influencing one of the witnesses in favor of its validity to alter his testimony. Happily, he was unsuccessful.)

Hours became weeks of interviewing Sister Sylvia about everything I could think of about what life on Bayou Teche was like in French-speaking St Martin Parish of the 1940s, as well as what her parents and grandparents may have told her about their days at the turn of the century. Hours spent on Ancestry.com building her online family tree led to several phone calls back and forth with her brother Don and her sister Josie, tweaking each other’s memories and filling in the gaps.

As the family stories and memories bouncing back and forth brought color, humor and life to the black and white printed page of the genealogy chart, a trend started to emerge. We’d be pouring over census records, and the lists of children in a relative’s household sometimes elicited a quiet correction from her. “Oh, no, he wasn’t this man’s son, but his nephew, an ‘outside’ child of his sister who never married and died young when the boy was small”, or “she wasn’t the little girl’s mother but she raised her anyway, an ‘outside’ child of her husband’s from before they met”.

Sometimes it was heartbreaking . . . “She was the ‘outside’ child of his wife and a white man who lived in town near the church where she worked. It was the depression and times were desperate for them, with so many mouths to feed, so his wife accepted this man’s attentions, because he then began to contribute to the family, helping to put food on the table. What could he do? I know my parents knew who the father was, who everybody’s were, but no one talked to the children about it, ever.”

Sometimes it was tragic . . . “She died a few years after [the census]. They said it was pneumonia, from being up in New York, in the cold. She worked for a white family here, and when they moved to New York, they took her with them. But one of our cousins who’d moved there, he was an artist with the Harlem renaissance movement, she’d go visit him on weekends, and he was the one who told me what really happened. The man had gotten her pregnant, sent her to a back-alley doctor. Far from home, dependent on him for money…..”

But sometimes it was funny . . . “Everyone suspected that his real father was a man, real friendly, who loved to fish, walking up and down the bayou, and giving the fish away to the houses he passed while the men were out in the fields. Sometimes he stayed longer in one place than another.”

And sometimes it was real funny, especially to the ears of a true New Orleanian such as myself who takes little scandals in stride . . . “Oh, no, they weren’t husband and wife, but sister and brother, who never married and never left the family home. She was a character . . . took it on herself as a duty, she said, to ‘introduce’ every young man in the neighborhood to the things he needed to know before he got married. And of course, everyone in the neighborhood was cousins with everyone else.”

Something that really bothered Sister was the secretiveness of her parents and their generation, as well as those that came before, about who was related to whom, all the liaisons between the blacks and the whites, the children that sprang from them, and the shame that kept so many people from ever finding out who their real parents were, or worse, made them believe that who and what they were was something to be ashamed of. Her desire to record her family history was fueled by her desire to give these people, long since gone, their identities back and dispel the shame and secretiveness that today’s culture did not hold to so strictly anymore. No, more than that… the secretiveness that today’s culture now recognizes as less an indictment against individual morality within the Black Creole community than a consequence of circumstances and a cultural mindset forced on them by the white man’s slavery and Jim Crow laws. We were both keenly aware of how difficult life was for Louisiana’s African-Americans during the Depression years, especially those isolated by their French Creole language, and how few opportunities they had to escape to any other kind of life. And she seemed to share my acceptance of the flawed nature of the human condition, the inevitability of it, and my lack of judgmentalism.

As a graduate student in two separate social sciences, I was of the mindset to see the culture she described with objectivity, impersonnaly, as a researcher, in broad strokes of conceptual causality, as the consequence of slavery’s eradication of any form of family structure, kinship system or marriage ritual for the slaves, as well as the forbiddance of any and all education. But hearing her describe her family so intimately, her own first-hand experiences, her grandfather’s spectacles on the breakfast table as he read his paper from cover to cover over coffee every morning, her aunt’s massive wood-burning stove, her mother’s heavy, green, hand-hewn kitchen table piled high with her wonderful cooking that had family and friends stopping by “for coffee and a visit” just as meals were being served, the long, long walks every Sunday into Breaux Bridge for Mass at St Francis of Assisi, the Catholic church for blacks, down the road from St Bernard’s where the whites went, and the bizarre ways of a couple of the more quirky men in the family that got adults whispering, children giggling, and everyone wondering about the inbreeding, often not realized, so common in the isolated rural farmlands of French Louisiana across the centuries. She spoke of the communal way she and her many cousins were in and out of everyone’s houses for meals, sleepovers, and inevitably, baths in a metal tub put by the fire with water that had to bathe everyone that night, no matter how many or how dirty, in order of seniority. She spoke of her father’s savant-like ability to figure up his and his neighbors’ calculations throughout the year’s sugar cycle, though he had to leave school after the 5th grade to replace the men in the fields who went off to WWI, the financial losses she read on his face as the Depression led him to more and more drastic attempts to support his family, the pointless violence one Saturday night at the hands of some white teens that left a cousin of hers a changed man, the mules whom an uncle sometimes took his frustrations out on, much as he did his own sons, and the acquiescence of a family friend who couldn’t afford to leave a job working for a man whose sexual attentions she occasionally had to accept, and her husband, just as powerless, who had to raise the resulting child as his own. Sister put a face on the impersonal concept, her own face, and Don’s and Josie’s, and broke through the academic distancing like a bucket of cold water, evoking many different emotions in me.

I told her of a racial mystery in my family that had long perplexed me, and the frustrating secretiveness I had bumped up against. I told her about the time when I was first visiting my grandmother’s farm back in the 80s, being introduced around by the various old cousins of Tisolay’s and taking walks across the property. They had verified something Tisolay had once said about her uncle Adrien, who never married and stayed home to run his father’s farm until he died… that he’d had a child with a black woman who lived nearby. But when I asked my grandmother’s elderly cousins who the child was, and where the child was, and how I could find the child who would be my 1st cousin twice removed, they had only shuffled their feet and feigned ignorance. But sitting there with Sister 35 years later, the response I got when I asked if she knew anything about it floored me!

“Do I know him? I was raised with him! And his mother was my aunt, my father’s oldest sister Lydia, who never married and died young, before I was born. My father took in both her boys after she died, 3 years before I was born. No, the other boy was someone else’s; no one knew for sure. Everyone says it was a white man with a family further up the bayou, but she was working at the time for the priest of St Bernard’s, the white church, at the rectory, and I always figured it was possible that it could have been the priest’s child. She was a beautiful girl; and what choice did she have anyway, to say no to the man she worked for? And yes, I remember Adrien, too, a gruff old man I was kinda scared of, would yell at his mules so! I was the one who found him dead, laying in the grass outside his back door. I passed his house to and from my cousin’s house across the road every day. I thought he was just sleeping, but I went and told someone. I was 6.”

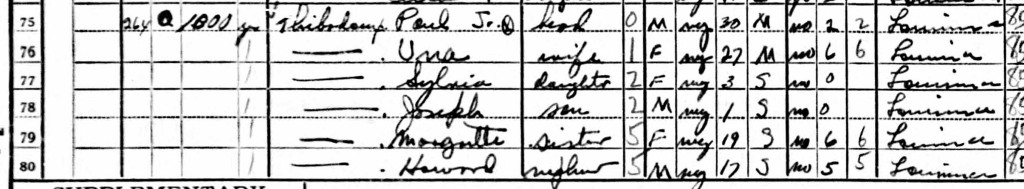

There he was in the 1940 census, Tisolay’s uncle Adrien’s son Howard, my 1st cousin twice removed, whom no one would ever tell me about, a 17-yr-old boy who’d lost the only parent he’d had when he was 10.

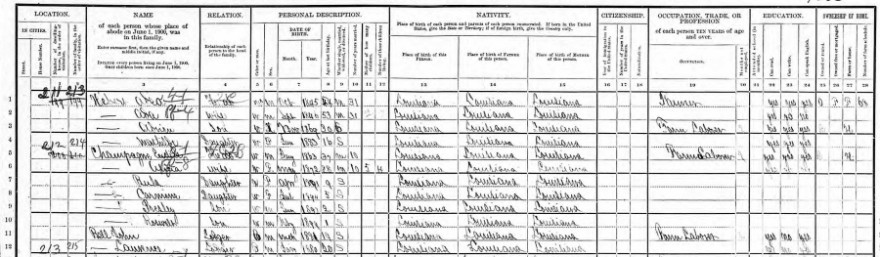

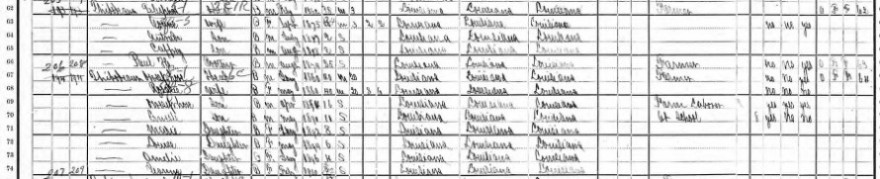

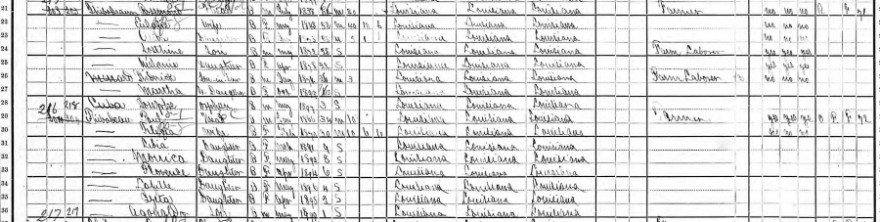

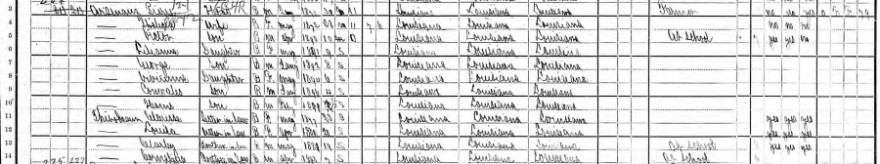

Much of the fleshing out of the family facts came from census data, which we poured over time and time again. Seeing a forgotten name would bring a flood of memories. Then when she’d call her sister or brother with a question, they’d have a flood of memories. Knowing the censuses as well as I did, whenever they needed a reminder, kept the flow steady, as well as the humor, and it was dear to watch. Studying the changes in the censuses from decade to decade, from 1870, when African-Americans were newly freed and included for the first time in the American census, to the most recently released census of 1940, illustrated the ebb and flow of family movement patterns and how openly families took in their unmarried siblings and children of hidden parentage. The census of 1900 shows the results of the 1894 succession court case 6 years earlier, fruits of Thelesphore’s leadership within the family. After the Civil War, newly freed African-Americans were in increasingly dire straits, working other people’s land much as they had during slavery, but without the room, board and medical care that had formerly been provided them. And with the ruin of so many white farmers after the abolition of slave labor, sharecropping opportunities were going to them first, making it more and more difficult for former slaves to find a patch of land sufficient to grow even a meager vegetable garden and graze a few chickens and pigs to feed their families, let alone large sugar cane fields where they could both work and live as sharecroppers. Very rarely did one find black families listed as homeowners or farmers on their own farmland. Over and over in the records, up and down the Teche, black and mulatto families were listed as renters and farm laborers on someone else’s farmland. But I had noticed back in the 80s, when I was researching my grandmother’s land, that just south of my gr-gr-grandfather Adeo and his family, in 1900, was a cluster of families identified as black or mulatto, every one of them listed as homeowners and planters on their own farmlands. Now, since reading the succession and researching with Sister, their names have significance as the 8 children of Onezime and Elizabeth, the 5 who were grown and married showing an”O” rather than an “R” at the far right where the census asks whether the family owned or rented their home, and the designation “Farmer” as occupation, rather than “Farm Laborer” for someone else.

It soon became a mutual desire to go visit her family in Breaux Bridge, which we did on Labor Day weekend 2014, staying with Josie whom I’d spoken to on the phone. We invited the researcher in Texas, the descendant of Oneziphore, the oldest of the 8, to join us, and we all met over a pot of Donald’s good Creole smothered chicken from an outdoor pot under his carport. I briefly visited the uninhabited field where I’d spent so much wonderful time in the ’80s, and the great oak by the water where I used to throw out my blanket, and the fascinating old ruin of a house on the land next door, between my grandmother’s property and the man who for 30 years had been letting me park under his pecan tree (my long-uninhabited property’s gates having long since rusted shut and become overgrown by weed trees.)

But mostly, we talked about the old family and got everyone we could on the phone with old family questions. “Why you wanna go rememberin’ all that ol’ stuff?” was sometimes the answer we got. But many were interested and came over to meet us and share old photos, etc. The star of the show, by far, was a copy of a portrait of Elizabeth, brought by the Texas relative, Ashley, whose gr-grandfather Oneziphore Jr, Onesime and Elizabeth’s oldest grandson by their first child, had brought it with him when he emigrated to Texas and hung it on the living room wall of his house, the house his gr-granddaughter Ashley now owned.

I had taken a few pictures of the inside of the abandoned house from the ground, through doors frozen open and unvisited for who knows how long, and asked the family if they knew whose house it had been. Turns out, it was Thelesphore’s, and one of the relatives who’d come to visit was his granddaughter Essie. In the midst of stories about him and his family in the old house, my ears did a double-take at something she said. Her father had remained in his parents’ home after his marriage and raised his family there so he could take care of Thelesphore and Corinne in their final years, but she herself, one of the youngest children, like my Tisolay, had not been born in her grandfather Thelesphore’s house. There had been a family argument amongst Thelesphore’s grown children after their parents died that had caused her father to move his family off the farm and out of the family home, and to cease farming the family lands; something about his not being given the house by the older siblings in consideration of his having stayed in the house to care for his parents in their final years. He didn’t go far, though. He went to work instead in the cane fields of his neighbor, my gr-gr-grandfather Adeo’s widow, Tante Sin, after the death of Adeo’s son Adrien early in 1942, moving his family into one of Adeo’s rental houses, less than 100 yards from his father Thelesphore’s house, down by the bayou’s edge under the great oak.

It was the house that Adeo’s daughter Tiwazzo (Alicia Hebert Champagne), my grandmother’s mother, had raised her family in some 50-odd years before, all except my Tisolay who hadn’t been born yet. Thelesphore’s granddaughter, Essie, was born in my great-grandparents’ house. Turns out, the concrete chunks that had lain toppled in the weeds under the oak at the bayou’s edge ever since I was in graduate school in ’87, where I’d bring my cat and my books, throw out a blanket in the shade of the swaying moss, and study, were the foundation piers of Tiwazzo’s house.

There were more trips, picking up Sister and driving the 2½ hours to Breaux Bridge, talking the whole way, staying with Josie, eating her truly fine Creole French dishes like duck fricasse (*warning: Jalapeños*) and stewed okra and sweet potatoes, and always my favorite, rice with her rich chicken gravy, cooked in the same kitchen as her mother had. Don and his wife Madonna would walk over from across the street to visit and eat with us, and sometimes cousin Raymond who had been letting me park under his pecan tree to get to my grandmother’s land for 35 years. From these trips came explorations and excavations that gradually split into 2 forms, an ethnographical biography of the family and an assemblage sculpture made from artifacts found around the property, a piece that grew over several years to foolhardy ambitious proportions.

Many times I wondered at the grace with which they took me into their homes and listened to a ‘clueless white chick’ (to my mind) ask questions about their lives as descendants of slaves that my ancestors enslaved, then once freed, repressed at every turn… one in particular, Adeo, in Onesime’s succession, who tried to deny his cousins their family name, home and livelihood. I wondered at the patience they had with my inexperience with the nuanced differences between the Black Creole and White Cajun French cultures. Goodness, honor, and a love of their God ran through the fabric of their lives.

I don’t remember when it was that I first studied Tisolay’s papers on the farm, which included my gr-gr-grandfather Adeo’s will, and realized that Adeo had not been living on Hebert land, as the presence of so many of his Hebert brothers across the bayou had suggested, but Thibodeaux land, and that his land had come from his mother, Phelonise Hebert, maiden name Thibodeaux, as her share of an old Spanish land grant to the Thibodeaux, bordered to the north and south by two of her brothers.

I don’t remember when it was that I put it together that the brother to the south, Onesime, was the same Onesime (there were many, up and down the generations and across branches) from the 1850 census, a 27-yr-old bachelor in a household of unmarried sisters and brothers working the land that had been their parents’ and grandparents’ for nearly 100 years . . . a household that, after the death in 1848 of their oldest sister Marie-Phélonise, included her little 3-yr-old son Adeo and his infant sister.

And I don’t remember at what point after meeting Sylvia I grasped that their Onesime, who married from his deathbed the former slave woman who’d borne him 8 children, was my gr-gr-gr-grandmother Phelonise’s brother, making Sylvia, Don and Josie my 3rd cousins, twice removed.

But they became more than friends; they were family… more than family, they were friends.