(cont’d from part 1)

What if the drayman, with his wagon backed up to the loading dock at the foot of Hodges St., were finished loading the Champagnes’ trunks and boxes and antsy kids, and simply led his horse straight down the loading ramp onto Hodges, never mind Railroad Ave. He’d pass John Isaac’s Southern Pacific Lunch (something) as before, but this time on his left. The whole right side of the first block was a bare field, apparently owned by the depot and left bare, presumably for parking carriages and wagons, picking up and dropping people off, and all the waiting in between. The left side was built up, but it had a different feel to it than the first block of Moss St with its shanties. It was more commercial, like a continuation of Railroad Ave businesses that wanted one last shot at catching the eyes of the newly-arrived or not-yet-departed, or those waiting in between, all parked right in front of them. Restaurant after restaurant targeted the hungry. It took a bit of work if you were a restaurant wanting to feed those who had to be in, fed, and out in 20 minutes, the time it took the train to take on its next load of wood and water. There were also soft drink shops, which made me remember a photo I’d seen in the archives a while back. The map that identified these buildings as soft drink shops was published in 1909, only 2 years after the Champagnes arrived, but something relevant had happened in between, in June of 1908, that may have made “soft drink stands” out of what had been saloons. There was a cluster of photographs of the event that merited captions from our intrepid Maude Reid, each with a slightly different slant. I’ll let her tell you.

~~~~~~~ the Prohibition vote ~~~~~~~

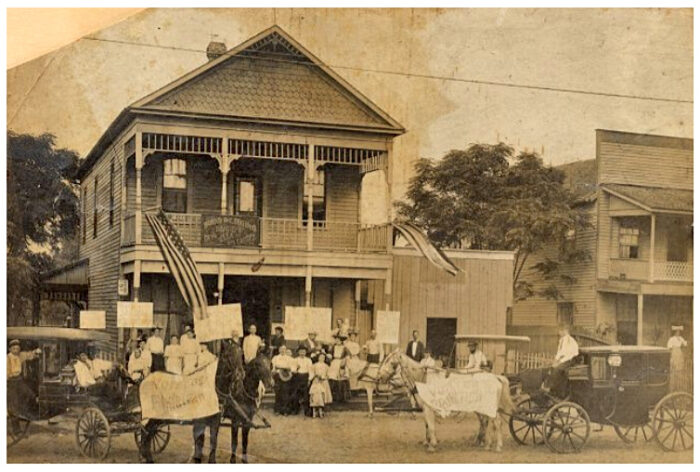

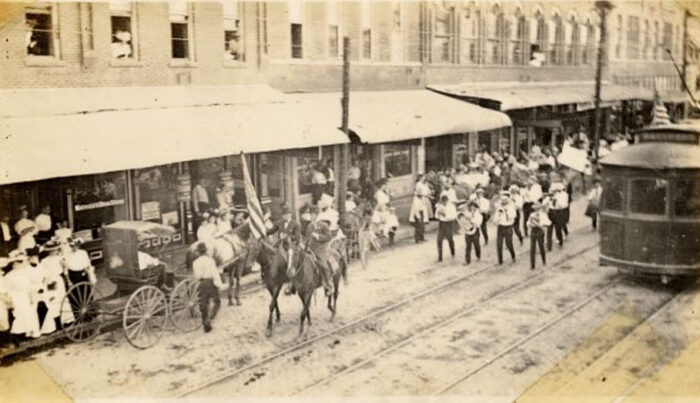

Podrasky’s, which at various times was a gen’l store, a restaurant and a boarding house, was about 4 blocks east of the depot. The day before the vote, there was a parade that marched down Ryan St to the Courthouse, where the voting took place.

“Headed by the First Regiment Band of Lake Charles, a parade of women and children, hundreds of them, marched down Ryan street waving flags and carrying transparencies with mottoes urging voters (men only) to vote out saloons in the town. Shelby Young, an attorney, and O.A. Throner, Methodist minister, headed the parade. This parade took place the day before a parish vote was taken on the liquor question for Calcasieu … Even the sisters from the local convent marched in the parade – for the first time – heading a group of little girls with banners asking that the voters ‘Protect Our Homes’ and ‘Vote for Us.'” – Maude Reid

🎶Well, Ti, here’s another one I can’t imagine y’all didn’t at least stroll over to Ryan St to see, a parade passing by on the day before the vote. Hmmm… June 8, 1908 was a Monday; would your dad have been allowed to leave work at the freight depot and meet y’all half way at Ryan St? It may have depended on the train schedule, which wouldn’t have changed for a little voting parade … 🎶

[… she laughs, having grown up in New Orleans which unapologetically grinds to a halt for the whole week of Mardi Gras, mystified that the rest of the country expects to find us still at our desks when their phone calls come in.🤣🎉🍾. No, trains don’t change their schedules to accommodate parades there either; I’m just sayin’.]

🎶I’m looking at the crowds of people. Are you in there somewhere, in Tiwazzo’s arms, or Beulah’s? Are you in the actual shots somewhere? Probably not. I recognize those stores, and they were in the 700 and 800 blocks of Ryan, west side. They’d have passed you back at Division or Mill St. Plus, y’all wouldn’t have been on the west side of the street.

I wonder. If your dad couldn’t come get y’all, would it have been proper for Tiwazzo to take y’all by herself, or would there have to have been a male escort? Presley would’ve only been 11 at the time. Surely, though, she could’ve walked the few blocks to the grocery store or meat market, and the parade wasn’t any further than that. You mentioned once that y’all had a cook, and you may have said that Tiwazzo didn’t cook. Grr – I don’t remember. Did she do the grocery shopping? Maybe it was Mathilde who didn’t cook and had hired a cook? How I wish I knew more about your family life back then.🎶

[I wouldn’t question the assumption that Tiwazzo was a traditional Cajun French cook if it weren’t for the fact that Tisolay never cooked a day in her life. Tiwazzo never taught her. And Granddaddy would’ve had a conniption had he ever seen her with a can of Bon Ami (like Comet) in her hands. He considered her job to be practicing the piano and raising my mother. That’s it. And keeping him company. In their elderly years, their long-time housekeeper retired, and Tisolay, in a rare existential moment, began to question her value as a wife if she couldn’t even cook her husband a meal. So she decided she was going to take over the cooking. I don’t remember how it happened, or what she did to the stove, but Granddaddy told the painters to leave the carbon star on the kitchen ceiling for last so Ti would be reminded to never attempt something like that again.]

🎶 Ah, Helen. Fifty years later and I can still smell your fried chicken. Standing there in the kitchen singing church spirituals, but in place of ‘Jesus’, it was ‘Laura’. “Ohhh, Laaaaaaaaaura, Showmetheway”.

Anyway, I know you were only 3, but that day may have had you in the midst of a rather celebratory atmosphere, and having nothing to do with the temperance parade. June of 1908 was when Beulah became the family’s first high school graduate. The 1940 census told me that Tiwazzo only finished the 6th grade (though her handwriting was exquisite, wasn’t it!), so why wouldn’t she be proud and feel like taking a stroll down to a parade. If your Daddy didn’t have any trouble leaving work, maybe he came and got y’all for a family outing, so you could walk with him down to the courthouse when he went to vote. How would he have voted? I never heard you mention anyone in the family being a drinker, and I know your daddy was an easy-going guy. Maybe he went ahead and voted for the family-friendly thing, though it may not have been a passion for him one way or the other. Who knows, though. Tiwazzo couldn’t vote, but she could have influenced him.🎶

Another of Maude Reid’s captions – “Here is a picture of the old-time ‘hacks’ that were used for passengers in our town until automobiles became popular. Here they are lined up for an election to outlaw saloons in our town. Lake Charles women were very active in this campaign and they were successful in having Lake Charles voted dry. The numerous saloons went out of existence.”

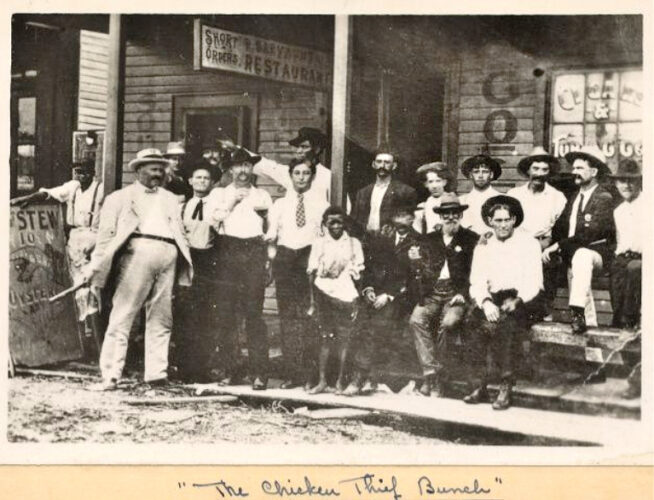

Well, Miss Maude, I’ve heard otherwise. Lake Charles probably did what the rest of America did and sent their booze underground, in the guise of, say… soft drink stands and restaurants. Just a few years before that vote, a group of Lake Charles men had a photo of themselves taken in front of a Railroad Ave saloon a few blocks east of Podrasky’s that the Champagnes’ train would have passed on the way in. Miss Maude seems to have enjoyed captioning this one, since she added to it several times over the years.

Chicken Thief Bunch, ca.1905, – “Photo taken in front of Richard Sarvaunt’s restaurant & bar on “Battle Row” between Reid & Kirkman. Notice the board advertising “Oyster Stew”, 10 cents. . . . . The bench that ~~ are sitting on, I was told by ‘Red’ Carlson, was not meant to be used for lying down purposes. It was alright to sit on it as long as you wished but if you dared to lie down, you would be instantly and none too gently knocked off. No place for drunks to sleep. . . . . This group got their name because they had been known to be careless as to where they got various birds, chickens or turkeys that they brought in to the restaurant from time to time, to be prepared for their delectation along with frequent mugs of cold beer. . . . The hawker was employed by the Battle Row saloon keepers to bring into town, every Saturday pay day, mill workers to be relieved of their week’s wages.” – Maude Reid

Miss Maude, you did have a way with words. But the restaurant sign doesn’t actually say ‘& bar’, it says ‘short orders’, another highlights oyster stew, and ‘Cigars and Tobaccos’ is elegantly advertized on the window glass. ‘Sodas’, ‘pies’, and ‘coffee’are painted on the wall… this place wouldn’t have had to skip a beat!. The chicken thief bunch wouldn’t have had to, either. I’ll bet the policeman seated at far right, his badge quite visible, kept right along going as he always had. I wish the 1903 Sanborn map, before the 1908 Prohibition vote, had written in the names of those 1909 ‘soda shops and restaurants’ that were along that first block of Hodges, cuz the signs out front when the Champagnes rode past, that’s what they really were.

The second block brings us back to the Foehr Islanders and the pioneer style houses from the early days of Lake Charles.

~~~~~ the Bendixens ~~~~~

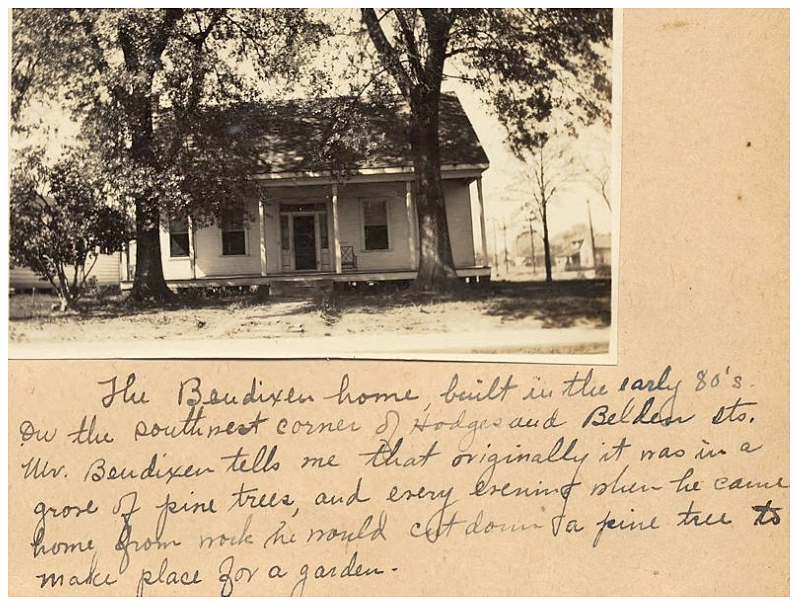

Volkert Heinriche Bendixen and his wife Johanna, 25 and 23, were betrothed but not yet married in 1872 when they climbed into one of Capt. Daniel Goos’ ships and crossed the ocean, together with many others from their homeland. The Frisian Islanders were unhappy with the recent transfer of their homeland, formerly, Danish, to Germany, and many families took the opportunity to send their oldest children, sometimes grown with families of their own, with Goos to Lake Charles and Galveston, Goos’ two centers of operation. And as these pioneers settled in, they brought other family members over, which is what Bendixen did, being the oldest son, eventually bringing all his brothers and a sister over. He was a carpenter for Goos and worked in one of his concerns in Vincent, a tiny settlement on the west side of the river south of town, possibly cutting trees since the mill was back in town. Many Foehr Islanders were loaned the fare for the trip by a family member who sponsored their immigration to Lake Charles, which in 1872 was $65, then worked for them, living with them for free, until the debt was paid. It would have taken longer to save the money to buy land, then build a house. I don’t know if this was how things were for Volkert, who by then was going by the name of Henry, but he was paid $20 (in silver dollars) a month for 14 hours labor a day, and worked for 9 years in Vincent before building the house on Hodges St.

In late 1880 or early ’81, though, he bought a plot of land in town, in the neighborhood where his fellow countrymen had settled, later known as Germantown because of them. It was 2 blocks from the German church, around the corner and across from a trading post. He must have been able to transfer to one of Goos’ work sites in town, because he told Maude Reid that, “he cleared the land of pine trees – cutting down one each evening after laboring during the day in mill work – until he cleared a space for this home.” According to Miss Maude’s caption to a companion photo of the Bendixen house, he continued on like this, clearing the way for a garden.

The house he built in 1881 was in the pioneer style traditional to early Lake Charles architecture. The railroad had only just finished cutting its way through the forests and swamps between Houston and New Orleans, connecting the major port cities for the first time.

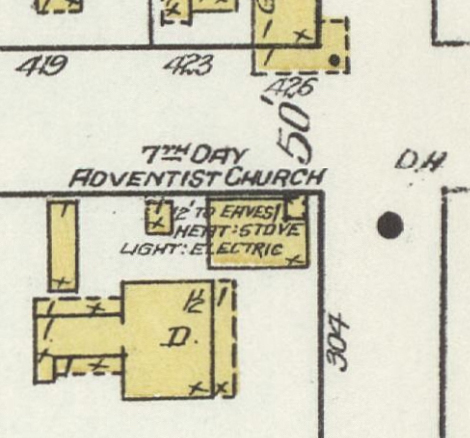

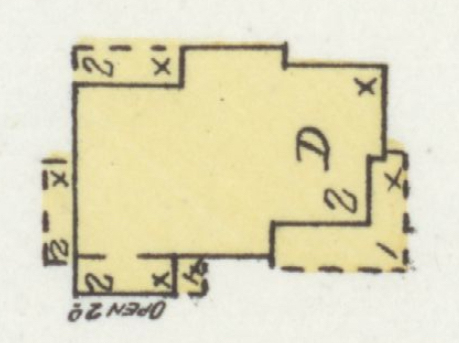

By the time the Champagnes got to Lake Charles, Henry was 60, Johanna, 58, they’d long ago buried their two little boys, and one daughter had married and left Louisiana. Their last child Emma, however, though she was preparing for an upcoming marriage to a Seventh Day Adventist pastor, was planning on remaining there with her parents and her new husband. Though Bendixen’s house was already a corner property, he built, some time between 1903 and 1909, a Seventh-Day Adventist church on the corner of the corner right in his front yard, uncomfortably squeezed between the house and the intersection. I wondered which came first, the church, then the pastor’s courtship of his daughter, or her marriage, then the construction of a church for his son-in-law. If he built the church to try to keep his last child and her new family with them, it worked, at least for the first 10 years of their marriage. But why build it where it was, invasively close, right up against the left side of the front porch where it blocked not only the light onto their porch but their view of the intersection with all its social flow of passing neighbors and friends?

Forgetting that I’d already found the church on a 1909 map, I wondered whether it could have been built where it was as one of those dire consequences of the 1910 fire that required fast action… like maybe his son-in-law’s old church had gone up in flames and land close to the town center had skyrocketed in price. I don’t know why the idea flashed into my mind to look up whether the 1910 census, which listed the church next to the Bendixen home as having already been built, had been taken before or after the April 23rd fire of that year. But I found the date in the upper corner of the page, and my blood ran cold.

I may as well have been looking at a 2001 census for Manhattan’s lower west side and seen that the page that some census-taker had carried around from place to place all morning, in the shadow of the Twin Towers, had been written on “9/11” of 2001, minutes before two Al-Qaeda-highjacked planes flew into them. Because the guy had been going from house to house, ticking off the little boxes on that day’s pages when he heard the alarm bells go off. The date at the top of the Bendixen’s 1910 census page is April 23. I almost expected to see a jolt in his handwriting, and little seared holes burnt into the paper.

Anyway, regardless of when the church building was built, it was taken down soon after the church transferred the pastor to a new town in 1917, taking the last of the Bendixens’ children with him. Before she left, though, the family took the opportunity to take a road trip to California to visit the Bendixens’ other daughter.

🎶By then you were 12; you’d probably seen this car going by with him in it, maybe he waved, missing the time when his daughters were your age. He’d watched you grow up. He died the year you married Granddaddy and left.🎶

That trip may have been the last time all four of them were together, because 2 years later, when he was 72, Henry’s wife Johanna died, on Jan. 1, 1919… (Happy New Year, Henry😪)… leaving him alone in an empty house for the first time in his life. A year later, the 1920 census shows him listed as a lodger in his own house, living with a family who’s renting from him, and he’s no longer listed as working. Ditto in 1930, but with another family. In the summer of 1931, he went to New York to visit with his daughter Emma’s family, intending to return before winter, but he didn’t. In November of 1931, he was killed in a car accident, run off the road coming back from a Seventh-Day Adventist church convention.

~~~~~

Past the Bendixens on the left, there were, and still are, two homes that are very different, one quite creative in its woodwork, the other simple, long and skinny with a dogtrot porch running along one side (since closed in) that was probably built as a rental. Both were rented at the time the Champagnes first rode by, though, the simpler one rented to the Railroad Ave merchant E G LaBauve, whose dry goods store the Champagnes would have seen back at the depot.

Then at the end of the block on the right, there was, and still is today, another house that Maude Reid captured in one of her freeze-frame memories.

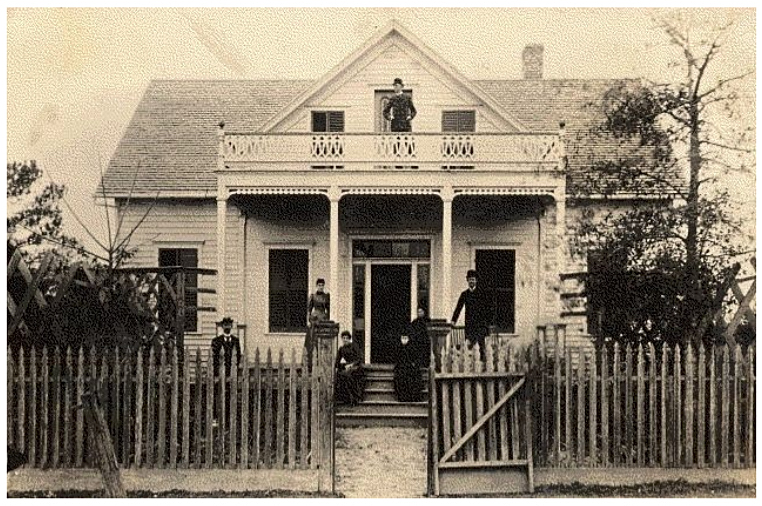

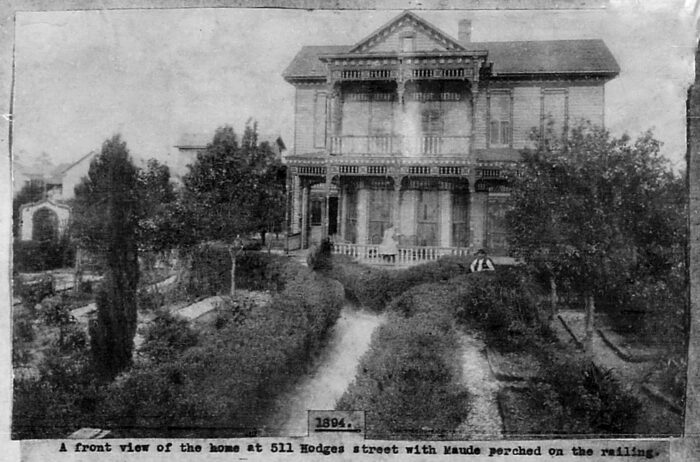

W W Durbridge, a man from New Orleans who’d been hired as a switchman by the Kansas City Southern railroad, was renting the house in 1907 when the Champagnes’ carriage first passed by. Long the home of Judge A J Kearney and his family, originally from the fishing community of Cameron on the Gulf Coast 30 miles south of Lake Charles, 1907 saw the house rented out temporarily during a reshuffling of the grown children after their widowed mother moved a few blocks away. Their son Johnson Kearney would marry late in life and move back in and raise his family there through the 20s, all younger than Tisolay. The above shot of the family was taken in 1894, 7 years after the cheerful, well-respected judge’s death. And Maude Reid, 12 years old at the time, remembered them all.

“Mr. Kearney came to Lake Charles from Cameron and was district attorney at one time, in the 1880’s. One of Judge Kearney’s sons was M. D. Kearney who had a drug store on Ryan street in the 80’s and 90’s. This picture taken in 1894, after Judge Kearney’s death, shows his wife and children. Left to right, they are – Milledge, Belle, Irene, Laura, Mrs. Kearney and Johnson Kearney. Upstairs, taller than the door, is Charlie Kearney. The house is still standing [1935], practically unchanged, in the possession of an Italian named Sam Navarro.” – Maude Reid

Long shaded beneath lush tall trees that were stripped to their bare bones by the 2 back-to-back hurricanes of 2020, the house now stands baking in the merciless Southern sun… but stand it does, still.

~~~~~ the Perkins family ~~~~~

The 2020 hurricanes took out many of Lake Charles’ magnificent 150-yr-old trees, some much older, but it is only because of that that Google Earth was able to give me a full view of this next great architectural hodge-podge, the Claiborne Perkins house that greeted the Champagnes on their left as they crossed Lawrence St into the 400 block.

There weren’t yet many trees tall enough in 1907 to obstruct the view of a house, so today’s post-hurricane view is probably much like when they saw it.

If Sanborn is any indication, the house itself is much the same as well. Its scale befits the family living in it. Claiborne Perkins was the 5th generation of his family in Calcasieu Parish. His gr-gr-grandfather Rees Perkins was the first justice of the peace in the parish that was mostly wilderness before Lake Charles was even an outpost.

Sometime around 1818, he built the storied Perkins Ferry just north of town that serviced Texas ranchers driving their cattle to New Orleans, sometimes carrying 2000 head across the Calcasieu in a single day. Maude Reid makes note on a photo from the 1920s of the ferry carrying a car, being pulled along a rope that spanned the river, that the ferry was still in use over 100 years after it was established, which would’ve been through Tisolay’s teens.

🎶Did you ever get on that thing, maybe with a bunch of friends, and help pull it along the heavy soggy rope that guided it to the other side?🎶

When the Champagnes’ carriage passed gr-gr-grandson Claiborne’s house, there were a lot of kids around, the ones still at home being the same ages as Tisolay’s older siblings, but none near her age. Mr Perkins was 47 and the Hodges St house was full of children then, but he, his family and his house were soon to lose the heart of the home when his wife Nancy died a year and a half later at the age of 45. If he were at all in need of his four oldest daughters’ help in running the house and raising the youngest 3, he didn’t have it for long. A year after their mother’s death, three girls had left home, and the fourth was getting ready to get married and leave. Even the children next door, the orphaned Runte children whose uncle took over their tutorship and let them rent the house under the care of their 19-yr-old sister Mary, had gone, taken in by Mary’s new husband Simon Baker Jacobsen down the block on Moss.

By the time baby Stella was old enough to know her neighbors, she would only have known Mr Perkins as a widower whose life had changed a great deal.

Across the street from the Perkins house, flush up against both corner sidewalks, was a 2-storey grocery store with a shady awning extending out over the Hodges St. entrance. It was nearing, or at, the end of its indeterminate lifespan as a grocery store in 1907 when the Champagnes drove by. Because by 1909, Sanborn shows the 2 storey structure as being moved back from the street, more toward the center of the lot, the awning removed, and having a new double verandah, full width, across the front. Mrs Cecile LeBlanc had opened up a boarding house.

Next door to Mrs. LeBlanc’s boarding house was a rental cottage with nice Eastlake gingerbread trim at its roof peaks. The Masons didn’t have any children, and they were only renting for a while in Lake Charles, as he was a railroad engineer that the company moved around. Today, like so many others after the 2020 hurricanes, it is no longer shaded by the tree we see here in the 2019 photo, which now only exists in photos.

A couple houses further down from the Masons were the Richardsons.

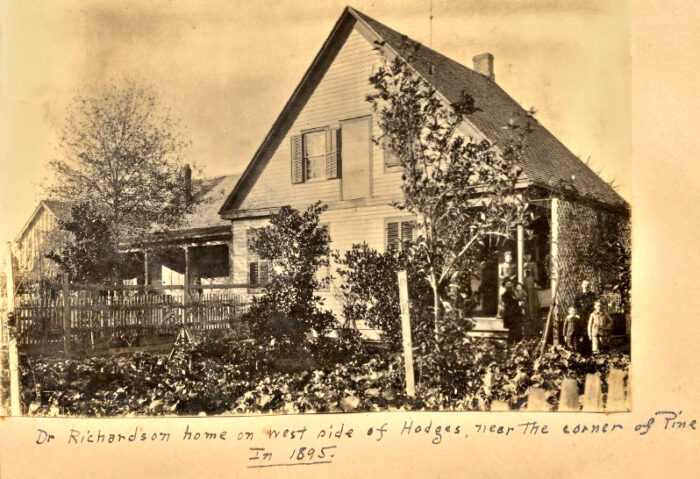

Clement Lanier Richardson was a doctor from a family of doctors in N. Carolina who came to Louisiana in the 1860s, and Lake Charles in the ’80s. Maude Reid captioned this 1895 freeze-frame of his family in the 1930s:

“This house built in 1883 by Green Powell, occupied by the Cagle family, then bought by Dr. Richardson in the 1890’s. Mrs. Richardson is on the gallery with her daughter, Mary, beside her. In the garden Dr. Richardson is holding Helen, …Shaler and Lanier are at the right, behind them stands Willie Richardson.”

When the Champagnes passed their house 12 years after this shot, the good doctor was a comfortable 65 and his wife Emma was 57, with only their last two teenagers still at home. Their oldest 3 had given them grandchildren, but none that lived in Louisiana.

~~~~~ The Hutchins/Reid clan ~~~~~

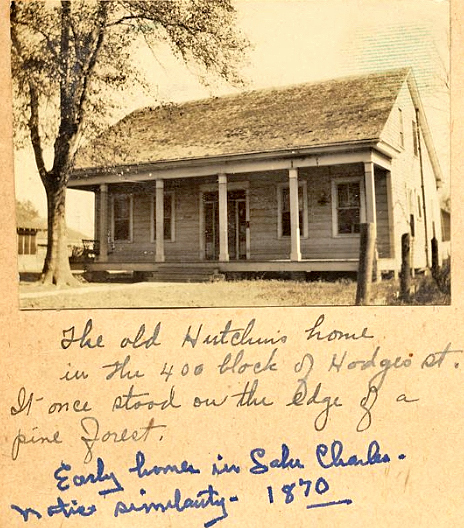

Across the street from the Richardsons was the ‘old Hutchins home’, as described in Maude Reid’s photo caption, home of William Louis Hutchins, Jr., who by 1907 was an elderly widower, his children grown and gone, all but the 17-yr-old daughter by his second marriage still living with him.

I don’t believe Miss Maude’s date on the photo, though. It is built in the old pioneer style, but the 1895 directory states that, “in the early part of 1883 . . . the houses owned by J.G.Powell and Judge D.J.Reid were the only houses east of Hodges Street.” I know both those houses. Plus, little hints of events surrounding its construction, which was a protracted affair, suggest it was completed around 1882-1884.

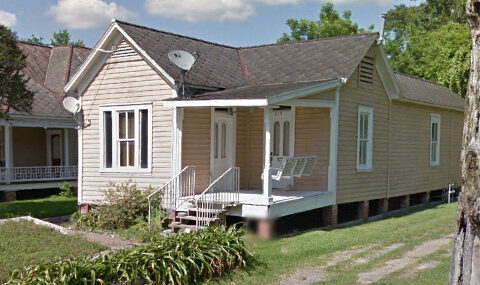

I think that the house currently on that site is the same house, which would make it roughly 140 years old.

Its porch has been closed in, which we’ve seen before, but the doorway and its side lights are the same. The roof has had a gable put in, fleshing out a 2nd floor space, but it still has its original two-window configuration on the north side. Most telling is the slender rear wing that extends off from the back, a bit off center, indicating that a porch had once balanced out the central position, just as it’s drawn on the early 1900s Sanborn maps. Strong bones these old houses had.

I don’t know if Lawrence St (now Pryce) which the Champagnes had just passed represents the property line that David Reid drew between the land he sold in lots to the Foehr Islanders in the 70s and the land he retained for his own family. South of Lawrence St, though, the story seems to shift from the Foehr Islanders to two families of English extraction, both by way of N. Carolina, then St Martinville in Cajun Country, though I haven’t found any evidence that they knew each other before reaching Lake Charles. David John Reid, Sr. and William Louis Hutchins, Sr. were also both in their early 30s in the 1850s when they moved their young families to the backwoods outpost of Charlestown, and both had young sons, Jrs, named after them. Reid we know as a builder of ‘colorful character’ who went into politics only because of an injury.

Legend has it that David Reid built this house, or at least started building it, early on. Frequently, throughout her wealth of writings, his granddaughter Maude says with pride about many of Lake Charles’ oldest houses (still extant when she was writing in the ’30s and ’40s but now gone) that “Grandfather Reid helped build this house”. One of her favorites was the old ‘Babe’ Rosteet home. From several shots and captions of the house, she tells us that the original house, built in the 1850s by her grandfather for Joe Charles Sallier, still existed in the center of the Rosteet house, which was built around it in the 1890s.

Joe Charles, son of Charles Arsene Sallier, the early settler that Lake Charles was named for, adopted a little girl left in his home for a few days by her father, a widowed friend moving to Texas with his only child. He had gone ahead for some reason and never come back, and everyone assumed that he’d been killed before he could return for her. The Salliers had no children of their own and the girl inherited the house, married Miguel Rosteet, and raised her family there, including ‘Babe’… who was a boy, by the way. Babe’s widow, Grace Lebleu, is pictured here with her friend Lorena H Walker, William L Hutchins’ middle daughter, in front of the house that ‘Babe’ expanded for her after their marriage some 50 years before.

I found the story of the orphaned girl that Joe Charles adopted poignant, but when Joe Charles was 13, something happened that really is, officially, the stuff of legend. His father, the original settler, had been one of Jean Lafitte’s captains sailing as privateers for one government or another, and sometimes for a fictitious government under forged papers. When Sallier settled his family on English Bayou north of Lake Charles, he served as a ‘fence’ for Lafitte’s stolen goods but also as a close friend whose family welcomed Lafitte into their home on the occasions when Lafitte sailed up the bayou to unload his ships into Sallier’s warehouses. One of Sallier’s children would later write down some of her memories of Lafitte’s visits. Like much of south Louisiana, Lake Charles didn’t ostracize Jean Lafitte as a pirate, but considered him a savior whose loot often saved New Orleans from crippling embargoes by the British. It was his fleet, offered to Andrew Jackson in exchange for amnesty, that won the Battle of New Orleans for the city. The lore, possibly exaggerated, is that Lafitte was in love with his good friend’s wife. Historians find no evidence of an affair, however, and simply feel that Sallier’s shooting of his wife the day before Christmas of 1819, when he saw her and Lafitte talking together, laughing, was a fluke flair of jealousy. Some say he saw his wife fall, then ran away in horror on his horse and never returned. Documentation exists that he started a new life elsewhere and had a child with a Native American woman, who would in turn have a daughter, Clothilde, who would briefly marry (and make life miserable for) John Martin Reid, the Judge’s even-tempered younger brother. (Still with me?🤣)

Interestingly, the family today is in possession of the amethyst brooch Sallier’s wife was wearing, possibly a gift from Lafitte, which still shows the marks of the bullet that hit it, knocking her over but not killing her as her husband had thought. Today, Contraband Bayou which flows through the southern part of Lake Charles into the lake is named in Lafitte’s honor (and has been much dug up by treasure hunters because of it), and the town holds a festival every year called Contraband Days in which the mayor is made to ‘walk the plank’ by the pirate-costumed population. Usually, this simply means being pushed, or pre-emptively jumping, off the town wharf.

While Reid was still building houses, before his political career had started, William L. Hutchins, a young newspaper printer from a family of printers in Opelousas, was settling into the new pioneer outpost at Charley’s Lake and starting up Calcasieu Parish’s first newspaper, the Gazette. He did not live to see the boom town that Lake Charles would become, dying 2 days shy of his 43rd birthday in 1865, but he did live long enough to see his son return from the Civil War. W L Hutchins Jr. enlisted in 1861 as a Confederate sailor when he was 17, re-enlisted in ’62 with the Cavalry, then was transferred to the marine department where he served aboard several vessels until the last one fell to Union soldiers. He was put in a federal prison in New Orleans, which had fallen to Union forces very early on, and his escape was noted in an 1891 biography of noted early Louisianians. I found a painting by Louisiana artist Robert Rucker that goes nicely with it.

“After remaining [in prison] for six months, he made his escape by boring a hole through the brick wall of the prison and made his way to Bayou Sara [near Baton Rouge] on the steamer “Empire Parish” as a deck hand. From there he went to Tunica Landing where he crossed the river and made his way through the Atchafalaya Swamps to Morgan’s Ferry. From there he went to Washington, La, thence home, on board the gunboat previously mentioned.” – William Henry Perrin, 1891

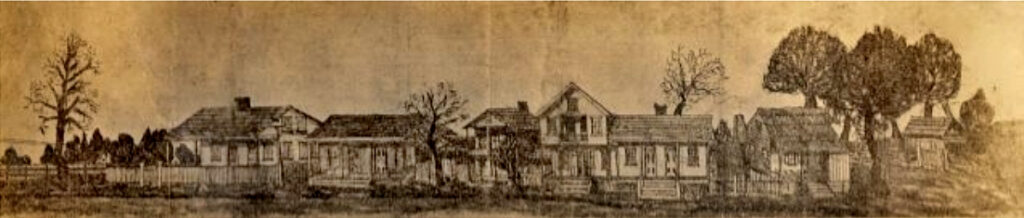

Hutchins Sr. did not, however, live long enough to see his son marry into a family that would become the ‘movers and shakers’ of Lake Charles civil service, the Reids. Despite the many difficulties people had with the temperamental DJ Reid, his daughter Eugenie’s marriage to the intrepid jail breaker just months after his father’s death was the first of several Reid/Hutchins partnerships that would bear fine fruit in Lake Charles. The town’s newspaper editor now gone, and Reid the new owner of the paper, Reid hired his son-in-law’s uncle Bryant Hutchins, a newspaperman like his deceased brother, to publish a new paper. The two Hutchins families, uncle and nephew, and the newspaper, are referenced in an 1870 drawing of the settlement’s main block of stores and businesses at the time.

🎶Oh, look, Tisolay. Louis S. Leveque’s house is in there, too. You didn’t know him; I know. Ask Carmen, she’ll tell you.🎶

Besides depicting Hutchins Jr’s general store, his uncle Bryant’s newspaper office, and the Lake Charles Hotel that was run by his aunt Marie Adeline, it also mentions Louis S Leveque. Bryant Hutchins and Judge Reid’s partnership at the Echo had been a trio, the third being Louis S Leveque whose building is in the drawing, and whose sister’s grandson, fifty years later, would marry my Tisolay’s beloved sister Carmen. But you knew that.

Anyway, at the time of this drawing, W L Hutchins, Jr, a 26-yr-old merchant with a store on the lake’s edge, was living with his 23-yr-old wife Eugenie, a toddler, and a newborn in a house built and given to them by her father DJ Reid. It was on a curve of the river north of town, next to a lumber mill that Hutchins owned.

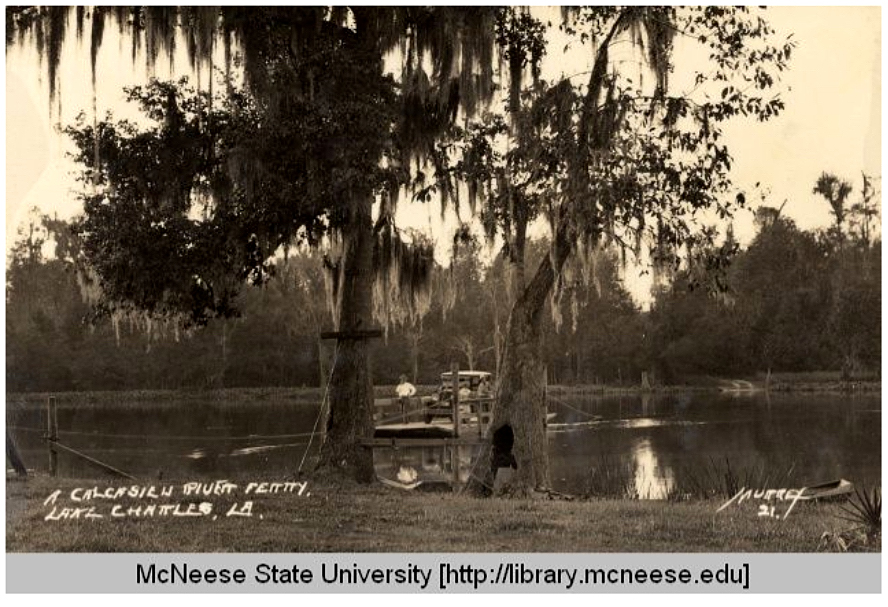

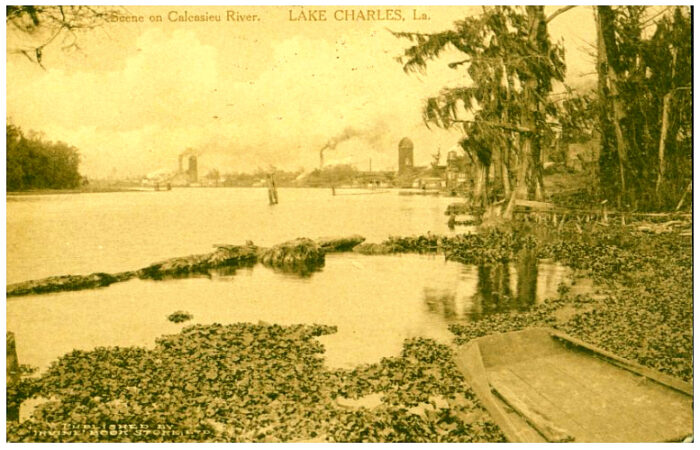

There’s an 1890s photo of the north riverfront from the vantage point of the Hutchins home, though they’d already moved to Hodges St. The little skiff in the right foreground is floating in a blanket of lavendar-spiked water hyacinths. Miss Maude describes the house as “charming, very pretty and rustic, on the bank of the Calcasieu River north of town, with a great yellow climbing rose covering the front gallery which was wide and cool. The children, however, were always sick with chills and fever and it was suspected that the place was malarial. The miasma from the river was considered unhealthy (never having heard that mosquitoes might be doing the mischief), so Grandfather Reid, who had begun the erection of a comfortable cottage on Hodges St, gave the unfinished home to his daughter Jenny”. I love how Miss Maude finished the last sentence, as it so discretely understates the amusing history behind the ‘old Hutchins home’ on Hodges St and the role played by DJ Reid’s own home only a block over and down. It also understates the best-documented hot-head among Lake Charles’ founding fathers. Too bad for him 🤣 that his granddaughter turned out to be the town’s prime legacy keeper and story teller.

~~~~~ the Hutchins and Reid homes ~~~~~

We know that Reid’s career as a builder ended when he was accidentally shot… some say in the arm, others say in the foot, but he kept his hand in, possibly using his sons for what he could no longer do. Reid family lore concerning the Hutchins home on Hodges St has it (though I have my doubts) that he was in the middle of building the house for his wife Mathilde as a surprise, since she’d been complaining for 2 decades about the “crudities and inconveniences of the primitive home Grandfather had first built when he came to Lake Charles in the ’50s, and which he had never improved. Finally, one day in a huff, she picked up her bonnet and left him – going to her daughter Jennie.” This and the following quotes and information are from Maude Reid’s family biography in the McNeese archives. Discovery of it is thanks to Trent Gremillion, Miss Maude’s present-day counterpart as haute Lake Charles historian extraordinaire.

Miss Maude describes the Reid home that her grandmother Mathilde found so uncomfortable as being still on the edge of the forest where the streets had not yet been cut through, which indicates that Lake Charles, a north-south strip along the east bank of the lake, was barely 3 blocks deep, with the forest only cleared maybe a block further. The house had four rooms downstairs with two bousillage fireplaces at each end (mud and moss squished into a wooden chimney frame like plaster), and was divided down the middle on the bottom floor by an open dog-trot breezeway connecting the front and back galleries. There was a set of porch stairs on the back gallery that led to an attic where the boys slept when their father, a multi-faceted entrepreneur as well as a judge, was using the residence as a courtroom and general business office. The kitchen and dining area was in a separate one-room log cabin with an adobe fireplace about 30 feet away.

I’m with Madame Reid. It sounds like a lot of exposure to bad weather rushing through a wind tunnel barricading one part of the house from the other, never mind having to run 30 ft to the dining room to eat, several times a day . . . for more than 2 decades . . . in hurricane country. Building a house that sits half-finished for 20 years, but suddenly it’s a present for his wife? Yeah. So she left, the judge stopped work on the house, never spoke to his wife again, and gave the house, unfinished, to his daughter Eugenie (Jenny) and her husband, William L Hutchins, Jr. In his defense, though, Miss Maude makes note that it was a stress-ridden time for the judge, the end of the 1870s.

“In 1880, David John Reid became a candidate for the office of Sheriff once more – a position that by this time had been more important to Southwest Louisiana and Imperial Calcasieu than that of the Governor of the State. But Reid was defeated for this office – the first election defeat that he ever suffered – and the last. I have been told that Judge Reid never forgave Thad Mayo for the part he played in the campaign when the contest was between himself and Dr. Munday for Parish Delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1879 [the convention that abolished the position of judge that Reid had held for decades]. Many years later, Mrs. A. M. Mayo [Thad’s nephew’s wife] told me the following anecdote. It seems that among all the horses, sheep, goats, hogs, etc., Grandfather had a number of pea-cocks, the admiration of the village. These pea-cocks used to strut about the grounds, with tails spread out, making a noise very much like – may-oo; may-oo – and after their political quarrel in 1879, Grandfather’s attention was called to the noise these creatures were making and how suggestive it was of his enemy’s name. He immediately had the fowls killed, saying that he never wanted anything about him that even remotely suggested Mayo…. I may add, parenthetically, that I consider this story apocryphal. I refuse to believe it!” – Maude Reid biography, McNeese archives

Miss Maude was born the year after the judge died, though, and never got to meet her irascible grandfather for herself. There were others, however, who described the judge mellowing with age. In his obituary, someone wrote that, “… he was ‘a good hater’, and strongly intolerant towards those who incurred his dislike, though, in the last few years of his life, he buried many of his old resentments, and made friends of many who were formerly his enemies.” Perhaps “Mayo”-screaming peacocks were just more than he could stand.

Mellowing in one person’s view notwithstanding, the 1880 census clearly paints a picture of the divided family dynamic surrounding this difficult man. The Judge is retired and living in the old Reid home, wind tunnel and all, with only his youngest two teenage sons with him who can now sleep downstairs where the judge’s offices had been. The attic now free, Reid apparently considered his wife’s departure permanent enough to have rented out the space to 5 working men, in boardinghouse fashion, with the help of an elderly widowed black woman for a live-in housekeeper who I imagine slept in a corner of the kitchen outside. In another house, the census finds his estranged wife Mme. Reid, 58, and his older son David Jr, 22, living with his oldest daughter Eugenie and her husband WL Hutchins Jr., now 32 & 35, in their charming cottage amidst the malarial miasmas on the river north of town, next to Hutchins’ lumber mill. David had been out of his father’s house for 6 years, since he was 16, first living with his Uncle John, the Judge’s brother, a man described by Miss Maude as amiable, and neither ambitious nor power-hungry “like his brother David”. John often employed his nephews at his butcher shop, and took them in when they ran away or were thrown out by their father, as David was. When William Hutchins gave his young brother-in-law a job at Mount Hope Mill; that’s probably when he went to live with his sister. David was listed as a clerk in 1880, but it didn’t say where. But the old judge may have regretted his behavior toward his son, because before his death in early 1881, he got his son a job with the city government. In any case, it must indeed have been a spacious house because, together with a houseful of 7 children between 12 and 1, they also have a guest living with them, May Helm, a schoolteacher from Galveston.

William L Hutchins, apparently a devoted big-brother figure to David, not only gave him a home and a job, but he also ended up finding the young man a wife, doing so in the capacity that earned him the nickname Captain Willy. And indeed, the marriage was one of the finer ‘apples to fall from the tree’ of Reid/Hutchins partnerships. Somehow, between running a general store and owning a lumber mill, William L Hutchins found time to captain a mail boat that ran between Lake Charles and Cameron on the gulf coast, going down one day and back the next, twice a week. He had befriended the Helm family from Galveston, a widow and the two grown daughters she’d followed to Cameron where they’d gotten jobs as school teachers, and often enjoyed supper with them. But in the summer of 1879, the tiny coastal village was wiped out, first by a hurricane whose storm surge washed much of the village out into the Gulf, then a typhoid epidemic which one of the Helm daughters, May, barely survived. (In her fever, she kept hearing the village carpenters hammering at what she was told were people’s homes being repaired, but were actually coffins being built from morning to night). After the storm, Capt. Hutchins heard that Mrs. Helm was planning to move her family back to Galveston. Hoping to prevent this, he offered to bring the ordinarily lively, fun-loving girl home with him for a few weeks of recuperation and a change of scenery. Maude writes amusingly of her dad’s courtship of her mother May and his propensity for practical jokes. May, whom Maude describes as “irrepressible, finding fun in everything”, must have delighted in witnessing, shortly after her arrival, David drawing a devil’s face and mustache on his big sister Eugenie’s infant son with charcoal from the fireplace. Eugenie, who’d said nothing, waited until the household was asleep, then crept into her brother’s room and beat him up with a stick. May almost threw away David’s letter proposing marriage, thinking it was part of one of his jokes. I imagine Eugenie’s mother Mathilde heard a great deal more laughter in her daughter’s home than in the Judge’s.

Oddly, May and her piano music charmed the Judge, and he would visit her in the bustling Hutchins home on the river, sometimes bringing others to hear her play for them. Once, lifting the lid of the piano for one of them elicited the response, “Look! The durned thing’s got teeth!” I suspect May could well have played a role in his eventual rapprochement with his son. The old man didn’t live to see his son and May married in December of 1881, though, because the previous February, at the age of 57, the cantankerous Judge Reid breathed his last. Nor did he live to see the ‘new’ Hodges house finished and the Hutchins gang moved in, which they did a few months before the wedding. But then, he also didn’t have to live through the loss of his oldest girl Jenny (Eugenie), Hutchins’ wife, the big-hearted (by all accounts!) daughter who never got to live in the house her father’d given her, instead following her father to the grave 2 weeks after him, taking with her the Hutchins’ 9th child born just 4 days before.

~~~~~ Hodges and Pine intersection, 1880s construction ~~~~~

Her husband and brothers David and Jack did, though, and timing suggests that that’s when they threw themselves into construction projects on 3 of the 4 corners at Hodges and Pine. The Hutchins house was built and moved into by the end of 1881, finished by David and Jack and their sister Mary’s husband Peter Broderson (one of the Foehr Island seafarers), in time for David and May’s wedding. In the Spring of 1882, the young Broderson family moved to Oregon, taking the Judge’s widow Mathilde with them.

William Hutchins was not absent from the construction boom on Hodges and Pine, though he was not a builder as the Judge had trained his boys to be. When Eugenie died at the start of 1881, I’d imagine the long-widowed Marguerite Eulalie Hutchins, who’d been living with her daughter’s family, moved into her son’s home on the river north of town to help with the kids. In January of 1883, though, William L Hutchins got remarried to Lizzie Hennington, whom he may have met through her older cousin Leanna, the wife of Dr. Abram H Moss who’d just bought the old Reid home and was building a new house there.

I think it wasn’t until then that he had a little cottage built for his mother, catercorner from the house he would soon be moving his family into. While it was similar to the old Hutchins home in its pioneer styling, begun by the Judge back in the 1860s, it was obviously finished after such Victorian features as bay windows and ornamental column brackets were found on even the simplest of houses. And that would most likely have been after the 1880 completion of the railroad that first opened Lake Charles up to the architectural influences from both Houston and New Orleans.

Maude Reid knew her Uncle Willy’s mother, the Widow Hutchins, when she lived there, and knew the tenants who came after she died, some of whom she wrote of with affectionate familiarity.

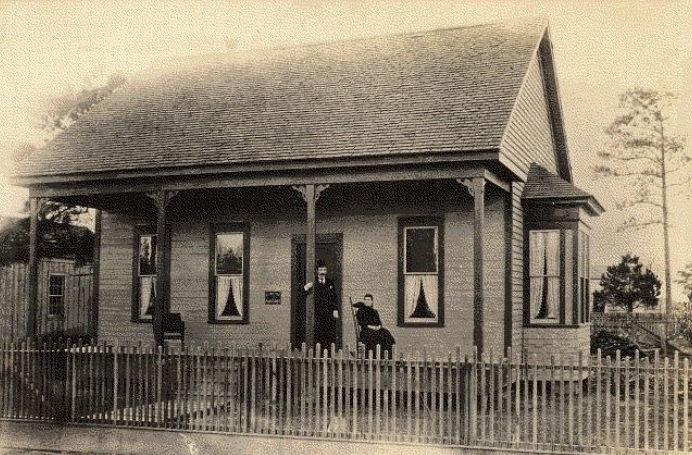

“The MacIvers were neighbors of ours when we lived on Hodges street. Mr. MacIver, a quiet little Scotchman, was a piano tuner; his wife was a lively little Jewess from Philadelphia. They are shown sitting on the porch in the picture. This house originally belonged to Mrs. Wm. Hutchins. It was occupied before the MacIvers took it over by a family named Folks who had two boys, Ernest and Luther. The house has now been moved back on Pine street and is a wreck.” – Maude Reid

In 1884, David won his father’s lucrative position as both sheriff and tax collector, the latter earning him commissions, so he hired a couple of his friends to build a different kind of home for him and May, one of the finest Victorian homes in Lake Charles up to that point.

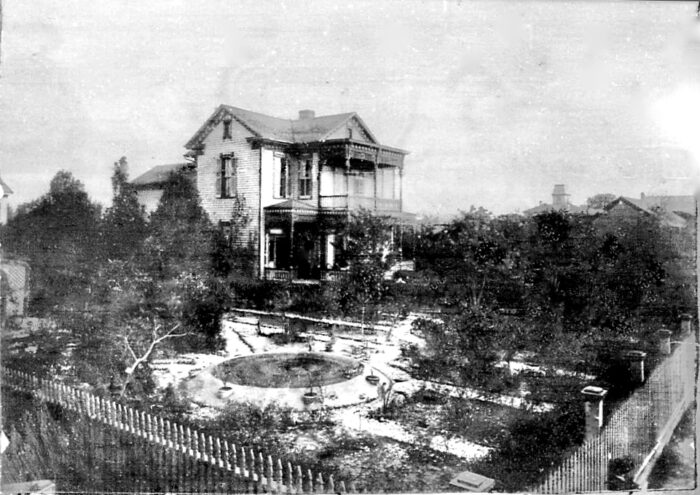

Miss Maude writes fondly of the house that she and her 3 younger siblings grew up in, as well as the magnificent garden to one side of the house. The pride and joy of her father, he’d designed it after Jackson Square in New Orleans. A lush orange grove opposite the garden was home to a crane who lived and roamed free, “giving the kids a run for their lives” on a regular basis. The orange trees, seen in the 1894 photo at right, will not survive to see another season. A freak unprecedented snowstorm in just a few months, in February of 1895, will kill them down to the last tree.

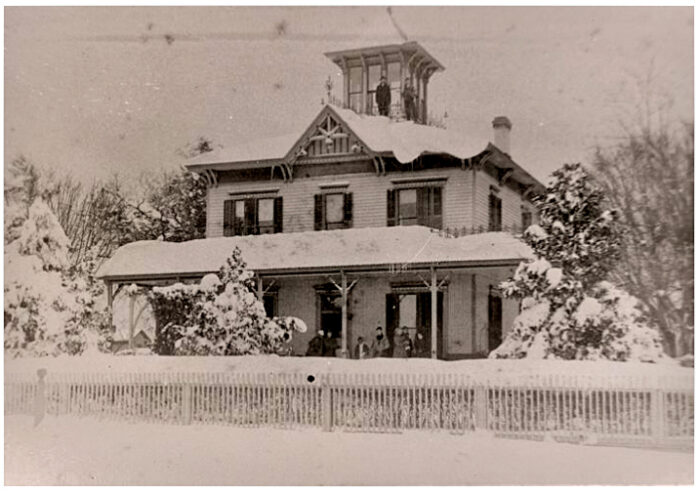

I found it hard to imagine snow like that in South Louisiana until I ran across a shot of the Moss home, around the corner from the Reids, taken after the snow let up. In fact, the Moss home was on the site of the old Reid home. And the rear property line of David’s new house abutted perpendicularly to the old Reid home site where he’d grown up. Dr. Abraham Moss, who’d torn down the judge’s old west-facing wind tunnel of a house, built his home “right between the trees Grandfather Reid had planted around his own home”, but facing south.

Actually, I should call it the Moss/Bel home, because you already know this house, though you wouldn’t recognize it except for the cupola. Moss sold it to J A Bel, and over the course of 2 remodels, Bel created the magnificent Bel mansion that you know from the photo I found in the McNeese archives of my 8-yr-old grandmother in front of the house at a Bel garden party.

Now that’s snow!

There’s an earlier shot of the house that must be from the early 1880s, not long after Moss built it, because the Widow Hutchins’ cottage is plainly visible at left in the distance, which it won’t be after David Jr. builds his fine home right in that line of view.

Fourteen years after David Reid built it, around 1900 when he was 44, he sold his fine home and gardens and built another house 2 blocks farther down the recently-extended Pine St, passing Moss St for Ford St. I showed you this house, too, early in Part 1 of The Route Home, the house Maude Reid spent her entire adult life in. He sold the Hodges St house to Mrs. Julie Muller Marx, a forward-thinking, 13-yrs-younger-man-marrying (😉wink*) entrepreneur and founder of the hugely successful Muller’s department store.

~~~~~ Hodges & Pine intersection, 1907 ~~~~~

By the time the Champagnes arrived in Lake Charles in 1907, 20-something years had passed since W L Hutchins moved to Hodges St with his second wife, built his mother a house, and watched his brother-in-law David Reid build May a showpiece of a home and garden on the corner between them. In that time, the coming of the railroads had turned Lake Charles into a boom town. When the Champagnes’ carriage passed the old Hutchins house, though, the good Captain Hutchins’ boom was nearly done. Still there at 63, widowed for a second time, nearly alone in the house except for his last child from his second marriage, a 17-yr-old daughter, William L Hutchins would be gone the following year. In fact, many things about the intersection of Hodges and Pine, stable for 2 decades, would be gone or changed within 2 years of their arrival, things baby Stella would not remember like her older siblings would. It’s possible that little Stella never knew the man living in the old Hutchins place, but she would know several of his grown children and grandchildren. Because the Reid/Hutchins clan of cousins that had put their stamp on the Hodges/Pine intersection had reconstituted itself a block away on Moss, where it would play a dominant role in the neighborhood the Champagnes were settling into.

Passing old man Hutchins’ house, then the bicycle shop on the corner, the Champagnes’ carriage would have turned left onto Pine just before reaching the Widow Hutchins’ house, by then the MacIvers’ home, which was in its last year as well, at least in its original location. I read somewhere in Miss Maude’s biography (McNeese archives) that Capt. Hutchins hadn’t wanted any changes to be made to his mother’s house after she died in 1890, not while he was alive. He died in October of 1908, though, and the 1909 Sanborn map shows that the little house had already been pushed to the back of the property and rotated to face the side street, just as Miss Maude said. This was how Tisolay would have grown up knowing it. Sold and used as a rental property, she’d have seen the deterioration that Miss Maude referred to as well, and its eventual abandonment when the stock market crashed. It was torn down 3 years later, the year after she married Granddaddy and left for New Orleans.

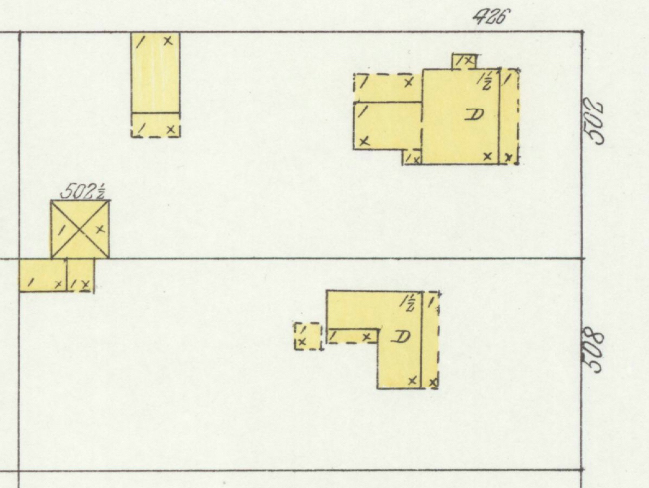

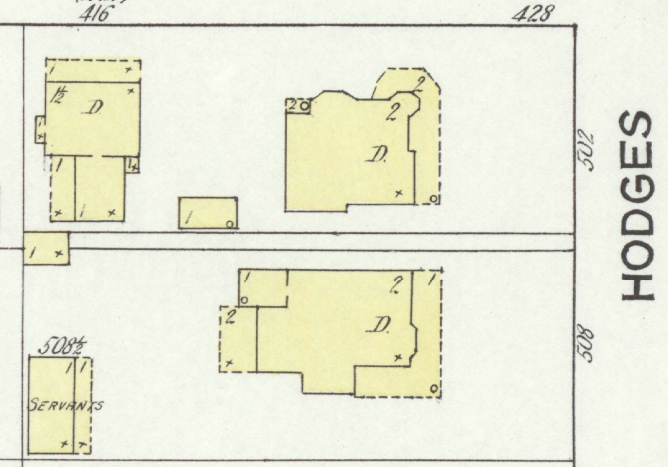

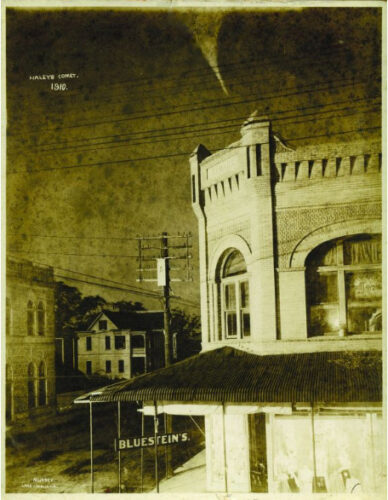

On the 1909 map, nothing had yet been built in the little house’ original location, but the following year, the 1910 census reported that the 502 Hodges address was again in use, this time by the family of Alex Bluestein, a well-to-do dry goods merchant from Germany, age 35, with 3 sons the same ages as Tisolay’s brothers Presley and Roosevelt. Sanborn’s 1914 map provided the first look of the Bluestein’s house, an outline of a grand 2-storey home where the Widow Hutchins’ cottage had been, with multiple bays and a J-shaped, 2-storey verandah with a large, rounded extension at its corner. This is the house Tisolay would have grown up knowing. She would have seen its damage and repair from the 1918 hurricane when its upper verandah collapsed. It was replaced as before, but subsequently, as with so many other houses who wanted to turn verandahs they no longer used into rooms, the southern end of the verandah was closed in on both levels. Today, it has apparently been divided into several apartments, but it got a much-needed facelift after the 2020 hurricanes and is again quite a beautiful home.

One of my favorite photos in the whole archive immortalizes Bluestein’s on the night that Halley’s comet flew by overhead. An almanac told me that it passed over Louisiana on May 19th, 1910, 26 days after the fire. The comet was all over the papers for weeks. The whole country knew its arrival date, and all of Lake Charles probably took a brief respite from the woes of its upheaval that early Spring night to enjoy the unique phenomenon. The Champagne family most likely went outside for a few minutes that night as well, to watch its slow crawl across the sky.

🎶I hope they brought you out with them and didn’t leave you asleep in bed. Remember Hurricane Betsy, when we rode out the storm at your house? Were you awake when Daddy brought me outside in the middle of the night? He must have had me up on one hip, half asleep, cuz I remember my face being right up next to his, looking up at the gaping hole in the thick spiraling blanket of clouds, and way up through to the clear black night sky above it all, a full moon. Everything was so still and calm and strange. Through the crisp air, the stars were like diamonds on a bed of black velvet. The moonlight showed the mess of fallen branches and leaves around the yard where a million puddled water droplets twinkled, but the rain had stopped After a while, it started getting windy again and Daddy brought me back in. I’ve always wondered if that night had anything to do with why I’ve never had a fear of storms.🎶

The Bluesteins didn’t have to live through the 1918 hurricane that took their upper verandah down. Though their big brick dept store downtown survived the 1910 fire, 1911 was the last year it was listed as Bluestein’s, and by 1917, the Bluesteins had moved to Texas.

~~~~~ Reid Jr/Muller house ~~~~~

Rounding the corner and leaving the MacIver’s house behind them, David Reid’s old house would have come into view. It must have been a feast to their eyes. It was no longer the Reids’ home, and there’s no telling whether his magnificent garden was still as it was. But the house, which the new owner would make some major changes to some time after 1909, was still in its original form when the Champagnes first passed it.

A unique trend, however, was becoming popular in Lake Charles architecture about the time Mrs Marx bought the place, that was replacing the delicate Eastlake Victorian columns and gingerbread millwork with a more imposing, slightly tapered box column with recessed panels that would come to be known as the Lake Charles column. A few who could afford it remodeled the verandahs of their old homes with the new Lake Charles columns, and that’s what Mrs. Marx did with the Reid home. Sometime between the 1909 and 1914 Sanborn maps, she extended the double verandah out to be flush across the front and supported the whole with four columns of the new style, moving the whole house closer to the street while she was at it. Maude Reid commented in admiration of Mrs. Marx’s change, saying that it replaced “that ugly Victorian front”. To each their own, I guess, but I loved it. I’m glad she only changed the exterior verandah and columns, and not the actual façade of the house, the ornamental door casings in particular.

🎶Ya’ know, your daddy would’ve seen the construction walking to and from work at the SPRR freight depot every day, watched them dismantle all the gorgeous woodwork from those verandahs. Those first few years, he’d have watched the new columns being built and lifted into place. He’d have seen the Widow Hutchins’ little cottage being moved and the fine Bluestein home going up in its place. Maybe he walked the family down that block every Sunday after Mass to see the progress on the various homes being worked on. It would have been something to watch, especially repositioning the Reid/Marx house. Y’all may even have known the family. Her 3 younger children, the Marx kids, were Carmen and Presley’s age. Maybe they walked home from Central School together. 🎶

~~~~~ Pine and Moss ~~~~~

When the Champagnes reached the intersection of Pine and Moss for the first time, they finally saw their new home, one door down from the corner on their far right. Were there any neighbors outside, sitting on their front porch? Young families? Any children? If there were, one would never guess how inter-related they all were.

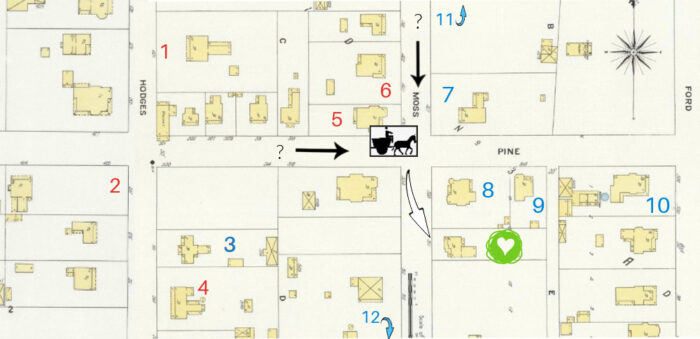

Lorena Hutchins Walker, Captain William’s daughter, now 36, was in the corner house directly to the left of their carriage as they sat at the intersection (#5 on the map), and her baby brother Thomas Bristow Hutchins (he of infant soot mustache renown) and his wife were on the other side of her(#6). Lorena and Tom had settled on the west side of Moss, sorta back to back with their father’s house(#1), across from two of their Reid uncles, Jack and Fred (#7&8), and their great uncle John Martin Reid (#11) on the east side of Moss. Lorena was nearly Tiwazzo’s age, 40, and had been married nearly as long, but she and her husband John B Walker never had children, which was very unusual at the time and often the source of shame and criticism for women. Let’s hope they took comfort in their many nieces and nephews around them.

I’m sure she was close to her closest sister Maggie’s kids who lived next to David and May back on Hodges(#4), 2 doors down from where she grew up(#1), 3 doors if you counted the bicycle repair shop on the corner. Her 3 boys and 2 girls, ranging in age between 15 and 3, were within friendship and flirting range of the Champagne children, the youngest, Beatrice, being exactly a year older than little Stella. Her Uncle David Reid’s older kids(#10) were in their 20s, Maude off in New York at nursing school, but his youngest two were Beulah and Carmen’s age and may have taken the same streetcar to and from high school. Her brother Tom, next door to Lorena, had a daughter Vena also a year older than little Stella and another on the way. Across from Lorena and Tom, on the NE corner, was their Uncle Jack, Andrew Jackson Reid, and his wife Annie(#7) who, at 45 & 40, had supplied Lorena with 8 young cousins the same age as Lorena’s own children would have been. Ranging from 19 to 4, they were also in the same age range as the Champagnes, their youngest, twins Audrey and Earl, being just over… wait for it… a year older than Stella (what was in the water that year?). Married to Jack now for 20 years, Annie, who’d been a Hennington from Copiah County, Mississippi, came to Lake Charles and married Jack 5 years after her older sister Lizzie, deceased for several years now, had come to marry Jack’s widowed brother-in-law, Capt. William L. Hutchins(#1).

Catercorner from Jack and Annie, directly to the right of the Champagnes’ carriage, before it turned right onto Moss, were Ernest and Floy Bel (#12) who had a daughter a few months younger than little Stella. It was in a photo of her birthday party some 5 or 6 years later, out on her grandmother’s magnificent front lawn, where I first found Stella, my Tisolay, at the start of my Lake Charles research, sitting in the grass in the front row of a big group kids. Their home, a wedding present from Ernest’s father J.A. Bel, was situated behind the grand Bel mansion Ernest had grown up in, on the south side of the block(#13). Floy was the daughter of Dr. Abram Moss, the man who’d originally built the Bel house after tearing down the old Judge Reid home. Dr. Moss sold the house to Ernest’s father several years after he hired him to manage his lumber mill in 1885, which might be when Ernest Bell, then 5, first met little 3-yr-old Floy Moss.

Floy’s mother had also been one of the Copiah County Henningtons, the first to come to Lake Charles. Floy was born around the time her mother’s cousin Lizzie was getting ready to come to Lake Charles to marry Capt. Hutchins(#1). Five years later, in marrying Jack Reid, Lizzie’s younger sister Annie would complete the Hennington chain, one of several to link the Reid and Hutchins families.

Ernest’s heritage, like Floy’s, had its share of family-intertwinedness. His mother Della was a Goos, daughter of Captain Daniel Goos and Catherine Moeling Goos, whom we’ve met in a previous post, Leaving Cajun Country. His father John Albert Bel was a step-son of his widowed mother’s second husband Friedrich G Moeling, Captain Daniel’s brother-in-law. When the young man J. A. Bel made his mark on the lumber industry, he married his step-father’s niece, Della.

But even the Goos family couldn’t beat the Hutchins/Reid clan for family intertwinedness, exemplified by the family of Alfred Joshua Reid and Mary Ellen Lanagan Reid, who built the house on the remaining corner of the Champagnes’ new block, the “witch’s hat house” next door to the Champagnes’ new home. But that story will have to wait for another time. It’s a sad tale, actually.

Alfred Joshua Reid was the last of the siblings to build a home on the old Reid homestead(#8), which he did some time after 1895. They’d been there less than 8 years when a 6-week battle with typhoid fever finally took him, leaving Mary Ellen with 4 kids between 10 and 2. Some time afterwards, she moved her family next door into her Pine St rental property(#9, whose back yard connected perpendicularly with the Champagnes’), and rented out their fine corner house, most likely out of financial need. The renter was a Dr Carlysle Hamilton and his wife Camille, newcomers from Illinois who would only be in Lake Charles for a few years; no children. As the widow Mary Ellen’s back yard met with Tiwazzo’s, she’d have known each other, as would their children who, like so many of the other Hutchins and Reid children, were the same age. The kids would’ve walked or ‘streetcarred’ the same path to and from school. The oldest of the 4, Alfred Jr, would certainly have been worth Carmen’s attention, since a newspaper photo of him as a high school track star a few years later shows that he grew up to be gorgeous! But that first year, Alfred was entering high school and Carmen still had a year to go before she’d join him. Sadly, by the second year there, I’m not sure Tiwazzo would have encouraged her kids to associate with Mary Ellen or her family. As I said, a sad tale.

🎶Aw, Ti. I love history, you know I do. And learning the history of your town and your neighborhood, and tidits about their private lives, does mean a lot to me. But are you in here? So much I wish I knew. So many children around you; were you friends with them? So many differences I imagine between your life at 511 Moss, and 5 or so years later, 617. Between the single family dynamic, where J Euclide and Tiwazzo lived as though their lives were their own to determine, and communal life with Tante Mathilde and Mildred, where financial and personality complications ensued. Or is my imagination making too much of Mildred’s bullying? If Uncle Michel hadn’t been hit by that train, and y’all had never moved in with them, how would things have been? That was the only unhappiness that you’ve ever admitted to, to me anyway.

It never occurred to me before, but what if it were Tante Mathilde’s money that brought a piano into the house and into your life? I think you’d say it was all worth it. Somehow that is hugely comforting to me, because I do think it was Mathilde who brought the piano into your home and your life. 🎶

~~~~~~~ cont’d on next post ~~~~~~~