(cont’d from previous post)

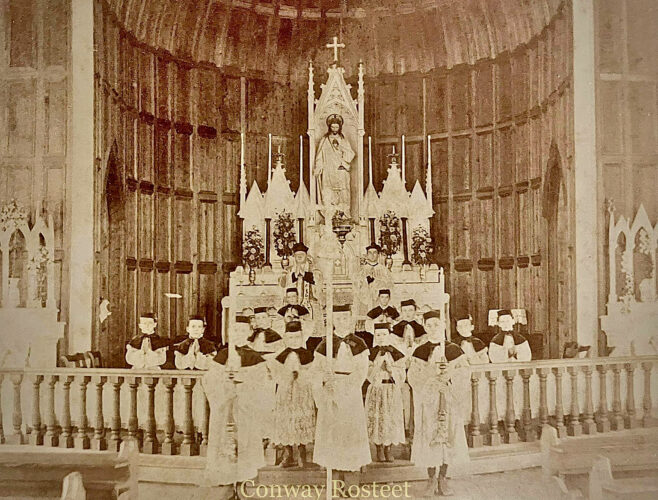

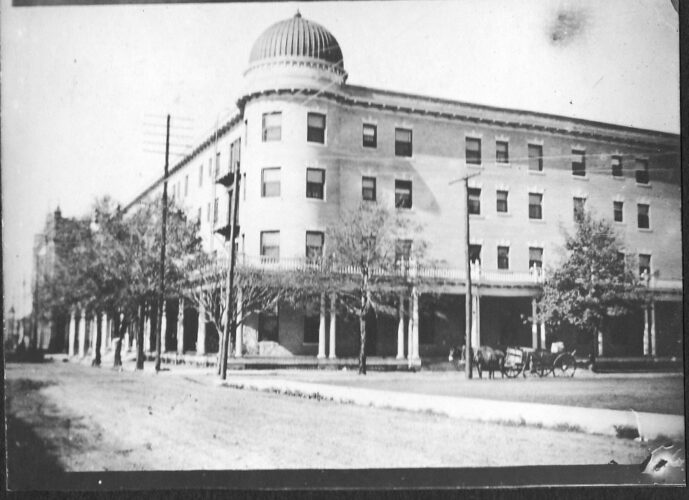

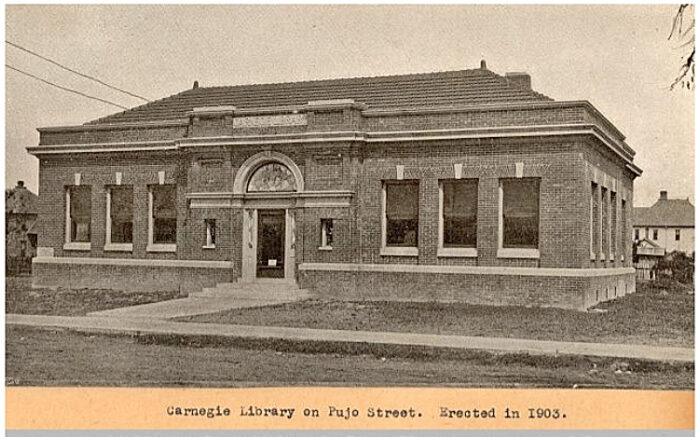

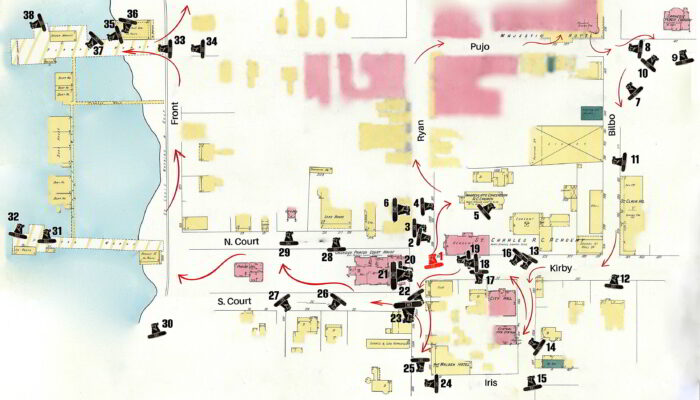

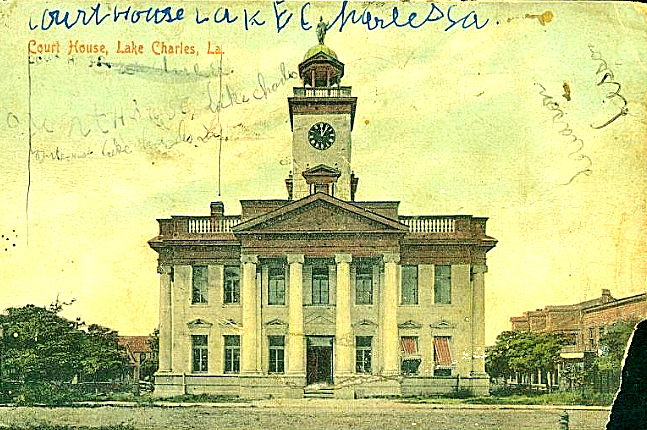

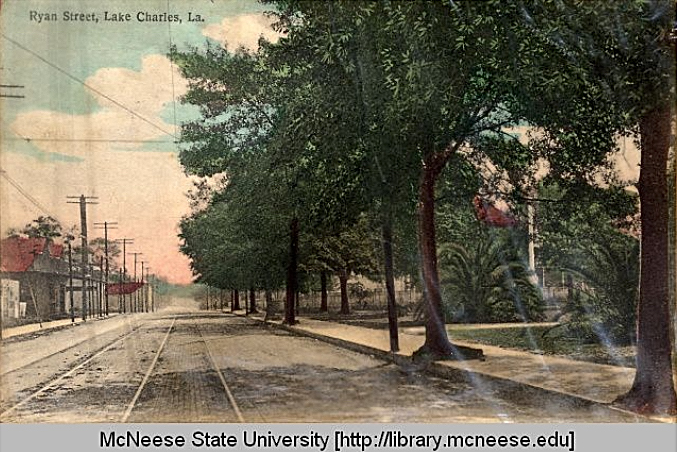

Of the 3 things I’m sure the Champagnes would have done around town, the first being J Euclide’s walk to check in with his new job at the Southern Pacific railroad’s freight depot on Division St, and the second being Tiwazzo and the girls’ initial shopping run down Ryan St, the third, going to Mass on their first Sunday morning, is the one I’m the most sure of. And unless the weather was bad, I’m reasonably sure that they would’ve made a leisurely, enjoyable family day of it, exploring around the small town center. Right after Mass, though, J Euclide would most likely have taken the family for their morning coffee and some breakfast, since Catholics couldn’t eat before taking communion. [As I say this, I’m filled with sadness, knowing that this was probably a time of optimism for a bright and financially stable future which, sadly, did not come to pass, and that J Euclide treating the family to breakfast somewhere was a luxury that would soon disappear from the Champagne family’s list of regular activities.] But this Sunday, I’m going to imagine the family going to the new Majestic hotel for brunch, built the year before, which Lake Charles would have been all abuzz about. From there, they’d wind their way around the back of the convent school complex, checking out the library and visiting some horses in front of a local stable along the way, then around City Hall and the fire station, then around the Courthouse and the town square, and finally to the waterfront and the ferry landing. Thanks to the McNeese archives, I have photos that illustrate the whole day’s path as the Champagnes would’ve seen it, an amazing majority being within 2 or 3 years of when they’d have seen it.

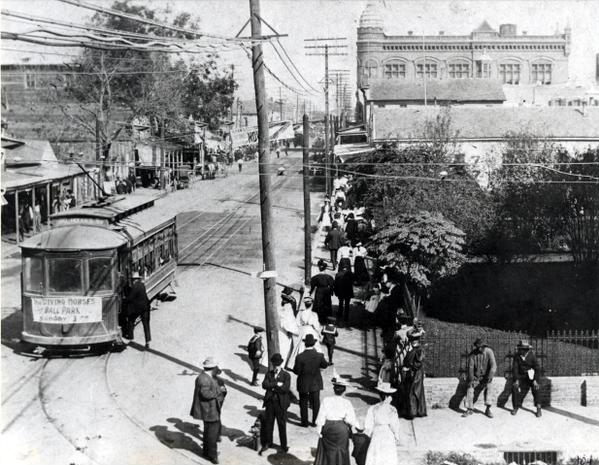

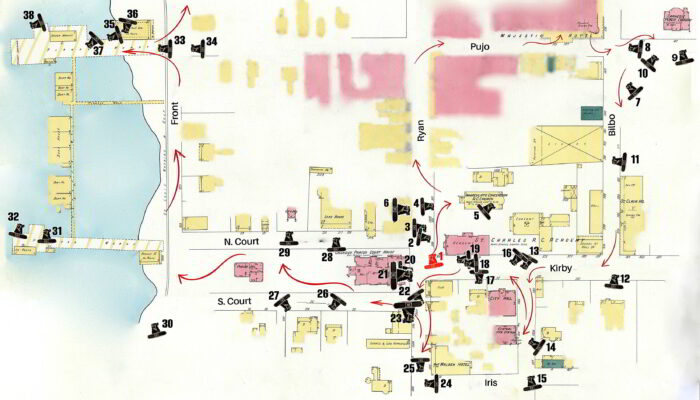

But first, after rallying everyone in the house to be dressed and walking a couple blocks to Ryan, I see them catching the streetcar which had a stop at the corner of the church complex in front of the school. There’s a wonderful photo from that very year, 1907, of a streetcar stopped at that corner, which gave me the perfect starting point for my map of the proposed route the Champagnes might have taken for the day’s walk. The starting-point camera, in red in the center of the Sanborn map guide, but it signifies a streetcar, which makes me think of it as “a little red streetcar”, a nod to someone very dear to me.

Well, ‘comin’ right out the gate’, it got bizarre. The banner on front of the streetcar reads: The Diving Horses at Ball Park, Sunday 3 pm. Diving horses??? So I googled it and got a poster for a travelling circus act in Atlantic City from the early 1900s. . . . Dear God!!!

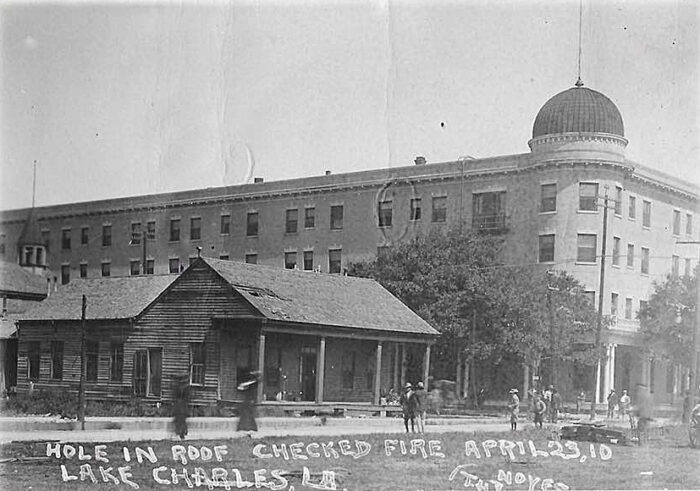

Leaving the Majestic after breakfast and turning towards the library on the opposite corner, the Champagnes would’ve seen, but not known the significance of, a small house 2 doors back behind the library, a modest house that the 1910 census says was being rented by a couple from Lithuania the Champagnes would later come to know, a couple who’d had 6 of their 7 musical children up in north Louisiana before coming to Lake Charles the year before to have their last. All of Lake Charles would come to know the Kushners, unquestionably the town’s first family of music whose further generations saw Juilliard educations, symphony positions and conductorships nationwide and abroad, and more recently, Tony Kushner’s Tony award for best play, “Angels in America”. But those newcomers back then… I wonder if, four days after the census page of April 19th listed them there, the Kushners saw the air above them filling with black smoke, walked to the corner in front of the Majestic and saw the water hose that the hotel had slung from its roof to the roof across the street, the old Knapp’s drug store with the Mansard roof. They probably couldn’t see the men on top of that roof hosing down the roofs of the little tinderbox storefronts all and the old Leveque house that stood between the Majestic and the wind-whipped, out-of-control blaze that was headed straight for them. I wonder what they felt in the split-seconds it took for their brains to grasp that they too were in the path. Did they do what so many other families were racing to do, pulling their most cherished valuables out of the house, hoping to secure one of the many horses and buggies that were moving frantic people’s possessions out of the line of fire, some of them losing everything to unscrupulous drivers they never saw again?

Turns out they didn’t have to. The Majestic did indeed succeed in keeping the fire away from it and all the little wooden buildings within their hose’s reach, and by the next year, the Kushners had built a fine home a few blocks further from the town center, across the street from Rudolph Krause, the Division St grocery store, and the only childhood home my grandmother remembers.

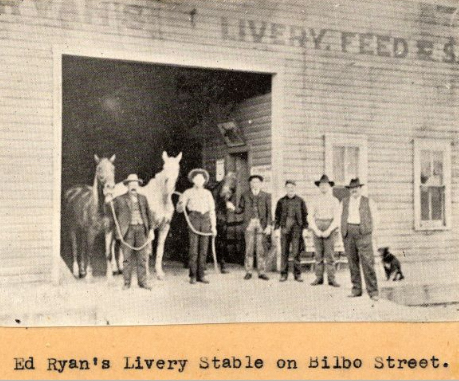

Caption for photo 11, by Maude Reid – “Men, horses, and a dog posing in front of the livery stable. This stable located on Bilbo street (just north of where the Catholic church now stands) was owned by Ed Ryan, a son of old ‘Pap’ Ryan – a pioneer mill man, and as interesting a personality as David Harum ever was between the pages of a book. He is shown at the extreme right of the picture with ‘Bob,’ his dog. He was an excellent judge of animals – man and beast – a great horseman, taking a great pride in his animals whom he treated with much kindness. If he ever found a stableboy abusing an animal in his stable, that boy was soon looking for another job. The stable burned in the fire of April 1910.”

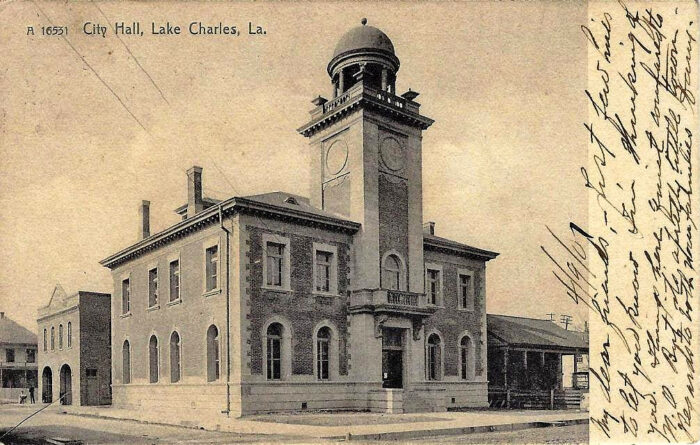

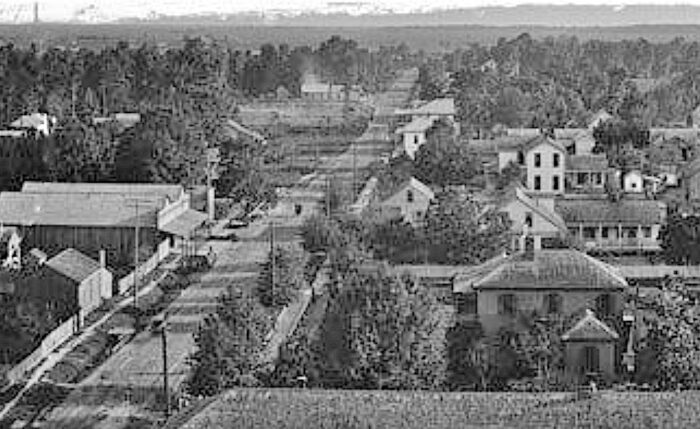

From left to right – the fire department, then City Hall. In line with the street is the cupola of St Mary’s convent, and at right, Mrs. Frank Gunn’s boarding house. – McNeese archives

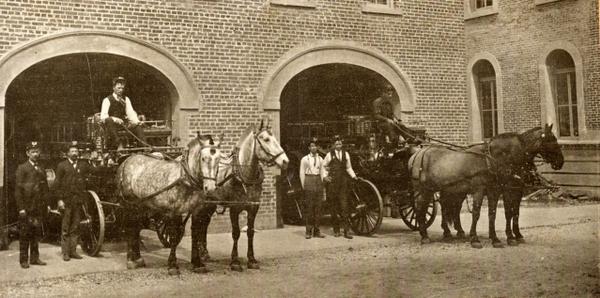

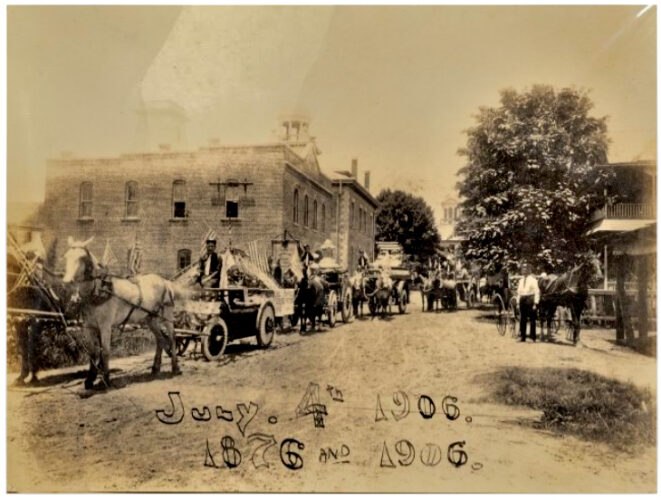

Caption by Maude Reid – “The little hand-pumper with which the volunteer firemen used to fight fires is in the front truck – so decorated with flags and bunting as to be unrecognizable. The steam engine is next, the “modern” equipment of 1906. Dick Gunn, fire chief, stands at right. The scene is on Cole St near the corner of Clarence. At this time the fire department was lodged in the brick building shown at left. The cupola of the city hall, which stood next to it, can be seen above the fire station.”

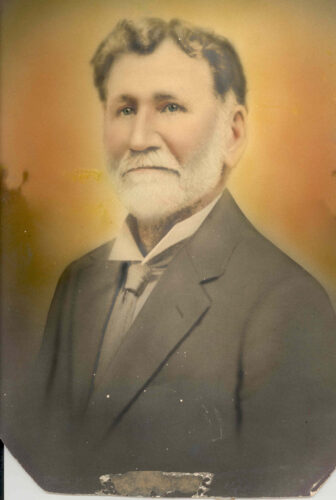

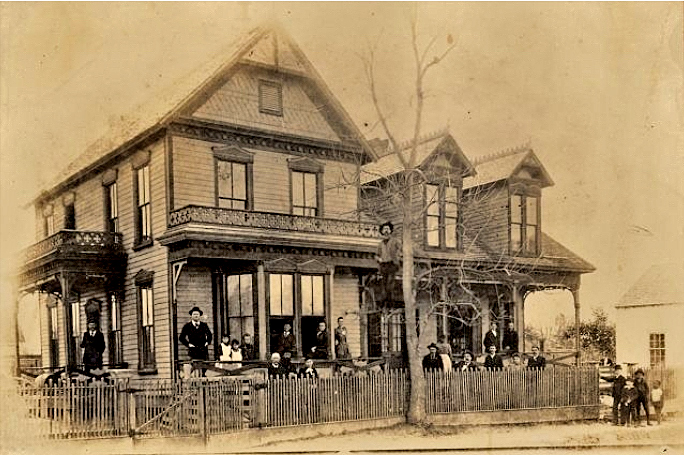

Judge and district attorney Edmund D Miller

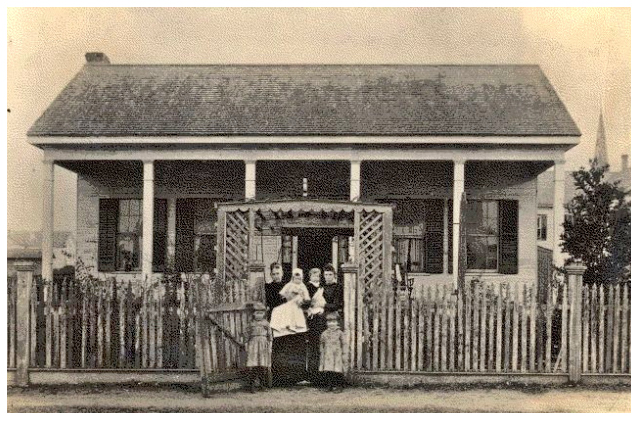

Just 2 years after the photo of Louella, Olive, and their children was taken, Olive died at age 30, and 3 years after that, Olive’s husband, steam tugboat captain Thomas Kaough, died on a hunting trip when he got lost on foot in the marshes. The 4 orphaned Kaough children ranging from 14-7 came to live with the Millers and their 3 who ranged from 8-5. I wonder how long it took the Millers to start thinking of leaving their trusty old pioneer home for a bigger place. Nine years later in 1909, when Pearl Kaough got married and brought her husband to live with the family, perhaps that’s when the Millers thought it was safe to let the new couple take over the younger Kaoughs’ care in the old Kirby St house, and get a place of their own. Cuz that same year, they did just that, on a sprawling piece of property south of Pithon Coulee in the newly-cleared area south of town.

I thought it was strange that the the following year, the 1910 census showed the Millers in their new place, but the Kaough boys still with them, but more so that they were listed twice, as also being with their sister on Kirby St. I figured that maybe it reflected a relaxed, unpressured transition, with the boys being bilocational as the spirit moved for a while. But I looked at the dates on the two census pages the two households were listed on, and that wasn’t it at all. The census page that showed Pearl, her husband, and her brothers living in the old Kirby St house was dated April 20th. Three days later, on April 23, their home in the old Miller house… actually their entire block and several surrounding blocks, were reduced to wisps of smoke and glowing cinders by the 1910 fire. Two days after the fire, the census taker – Who knows what kind of disruption this caused him – had made his way to the Millers’ neighborhood south of town, and the boys who’s fled there after the fire were counted again. Little did the Millers know that the open country feel of their new neighborhood would end within a year of them moving in, since after the fire, a building boom would turn the area south of the Pithon Coulee into the ‘hip’ new neighborhood of Margaret Place. Talk about disturbing their peace: the relocated St Charles Academy, newer and bigger, was built directly across the street from their front door.

I love rabbit-holes; they lead to discoveries and unexpected connections that can be wonderful… usually. Trying to find out why the Miller house disappeared, replaced by a new town park only 7 years after the fire?… not so much. Luella Miller was gone by then, too, re-emerging in 1917 in Houston listed as a widow, with her 3 grown children, never to return to Louisiana, and never to relinquish the identity of widow. Her husband wasn’t dead, though, and I think she knew it. Perhaps it was a face-saving mechanism. Cuz something happened within Edmond D Miller after the fire, and in the summer of 1911, the redoubtable 56-yr-old judge and attorney general totally went walkabout, packed his things, and abandoned his home and family. He must have made sure his wife knew he was leaving for good, cuz soon after, she petitioned the court to be allowed to perform the duties of his estate, saying that Miller had ‘permanently left’ his home with no legal action of separation, but also no provision for the management of his estate, which included rental properties. A year later, he did finalize a divorce, and then sailed to Japan, where he met a German woman at a friend’s party in Yokohama who’d been teaching languages to the children of foreign diplomats. When he came home, he settled in Jennings, 30 miles east of Lake Charles, where he took up his law practice again. And in 1916, the Jennings newspaper wrote unabashedly… in fact, a bit petulantly, that it and everyone was shocked to get a message from a Chicago paper, where he’d gone for a 3 week vacation, saying he had gotten married to a woman he’d met several years before in Japan, apparently having kept up correspondence. It was the first anyone had heard of her. From her ship from Japan, he had her travel to Chicago to marry him there instead of getting married among the people he knew. When she died 10 years later, he wrote to inform her good friend in Japan, also a German woman, corresponded for 2 years, then married her as well, this time in Cuba, ‘since he couldn’t get married in the U.S.’? Sounds to me like he filed court papers for a divorce but she refused to sign them, or the judge refused to grant one, which was common back then without proof of egregious fault. He knew the law: Perhaps by blatantly abandoning her, he was trying to give her clear grounds and the judge the proof he needed, except that she refused to file. When he died, the Jennings paper wrote up a long bio for his obit, with his schooling, his law practice in Lake Charles, his grown children named, but otherwise completely skipping the 28-year association with Luella Clark.

If only marriage to Edmund Miller had been the beginning and end of the tragedy in Luella’s life. It wasn’t. She and Olive were born in the middle of the Civil War to a white father with a wife and family, and a mulatto mother in the Opelousas area, the father dying in 1870 when they were 5 & 3. There is a record of his second marriage to their mother, Catherine, in the courthouse, dated 2 years before the death of his 1st wife. His succession, though, mentions nothing of a divorce from his first wife and neither provides for nor acknowledges his second family. Following his death, Catherine took the children and joined her sister’s family in moving from Opelousas to settle in Lake Charles.

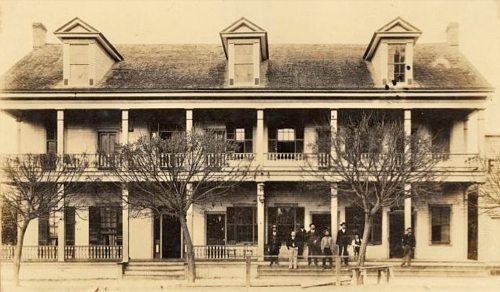

We’ve met her sister’s husband before, Julien Richard, whose store Miss Maude confused for the jewelry store next door, both built and rented out by old Monsieur LaFargue on the corner. On arriving to Lake Charles, he took over the boarding house on Lake Charles’ courthouse square in the 1870s from Mrs. Bryant Hutchins when her husband’s newspaper business took them elsewhere. And we know Julien’s sister Emelie, whose husband, attorney Louis Leveque, Carmen’s future mother-in-law’s uncle, partnered with Judge D.J. Reid to start Lake Charles’ first newspaper, with Bryant Hutchins at the helm. So when Luella and Olive’s mother died in 1877 at 41, orphaning them at 12 &10, and Emelie’s husband Louis, 43, died nine months later having never had children, the widow Emelie took them in. Finding this information was difficult and circuitous, and speaks to the legacy of shame and secrecy with which mulattos who ‘passed’ for white hid their black family lines.

For more tragedy, fast forward 3 decades after Luella is divorced and in Texas. Their son Edward died in a psychiatric hospital of ‘mania and exhaustion’ at 34, having never had a job or lived anywhere but with his mother. And their oldest daughter Fleta, after her husband finally succumbed to a long period of heart disease, died a few months after him “of a lacerated throat” – method, razor blade.

Jeez, let’s move on. And maybe let’s duplicate the map for convenience of back-and-forth-ing.

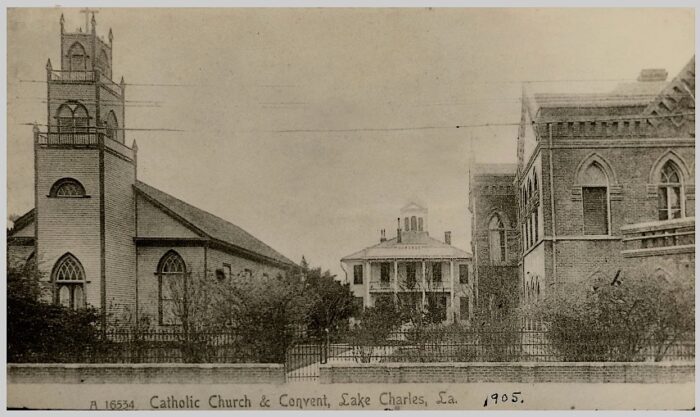

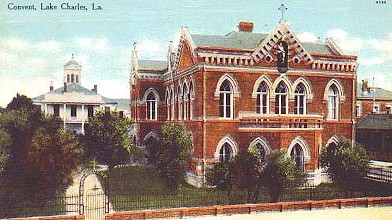

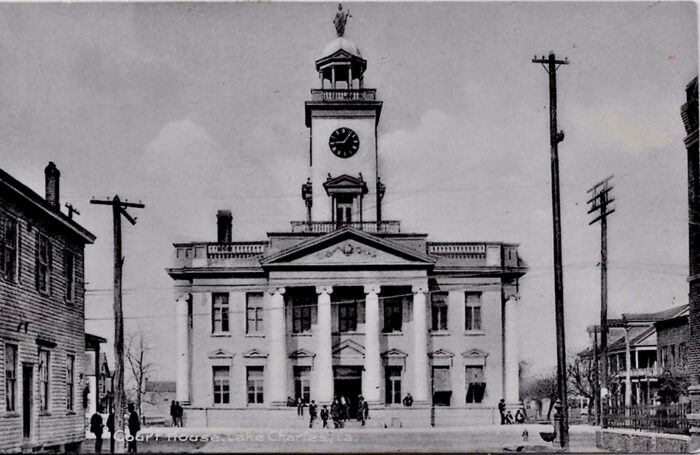

The return to the schoolhouse, seen in photo 18, and the streetcar stop in front of it brought the Champagnes full circle to the new brick school’s front yard where the streetcar had dropped them off. If they’d walked up the steps of the courthouse, then turned around to look back down Kirby St where they’d just come from, and then gone up to the top of the bell tower and done the same, they’d have seen a later version of the two photos below. Though these photos had only been taken 4 years before, much had changed. So many old wooden buildings from the early days had just recently been replaced by big brick structures… government buildings, church and school buildings, and large commercial/office complexes. What a shame that the fire was so intense that even the brick couldn’t withstand it.

With apologies to Maude Reid and her multiple captions for photos of the same places, I rearrange, and sometimes correct, bits and pieces of her information.

This little church-turned-schoolhouse, built around the end of the 1850s, was the original church that Miss Maude so proudly heralds as being built by her grandfather, Judge DJ Reid. You can just make out the cross above the little doorway parapet. In 2 years, the large Gothic brick school building that greeted the Champagnes when they got off the streetcar for Mass would replace it. In the distance, hidden by the convent’s trees, is the newly built St Clair boarding house, from photo 12. – McNeese archives

From the bell tower, a slight turn of the head south from Kirby St toward Ryan, and they’d have seen the Walden Hotel in what had been the United Staters Hotel 12 years before, then the complex of offices, lumber milling rooms and storage houses of the Mutersbaugh planing mill.

After seeing the view from the tower of where they’d been all morning, they’d come back down to turn into the courthouse square and head toward the lake.

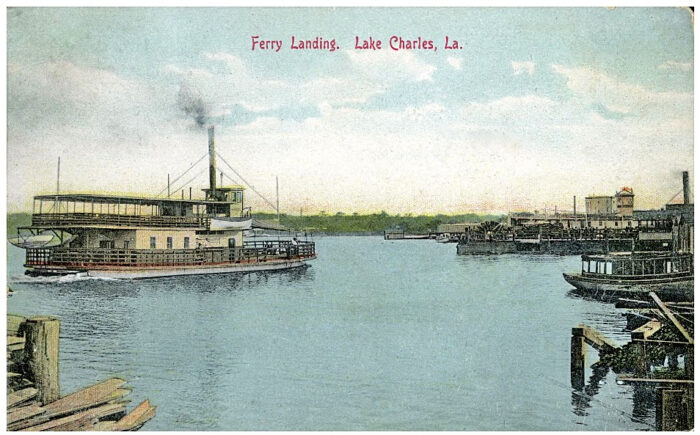

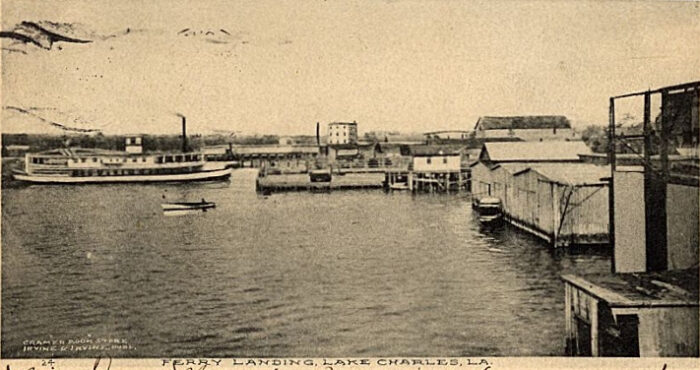

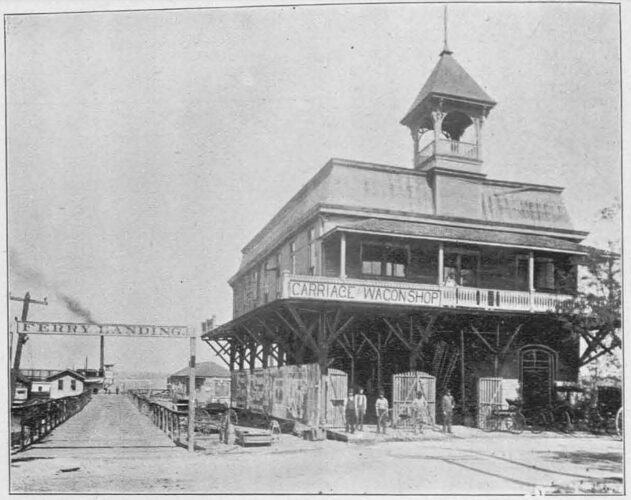

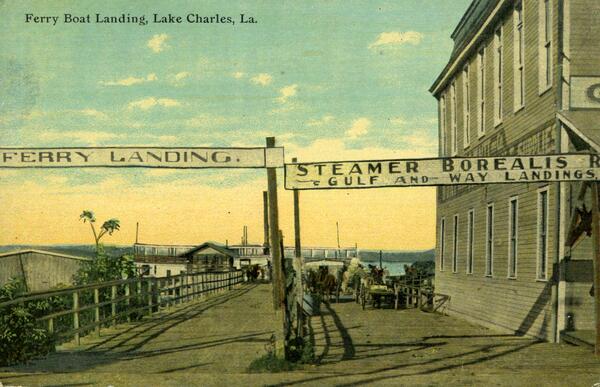

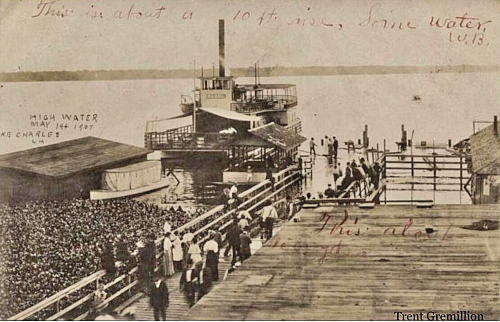

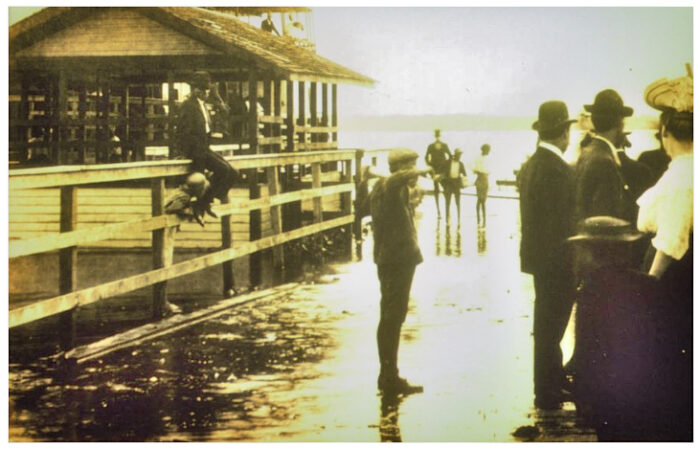

The Champagnes just missed seeing the May 14th flood of 1907, with its waterline being above the end of the wharf, keeping passengers from reaching the ferry and washing millions of water hyacinths ashore.

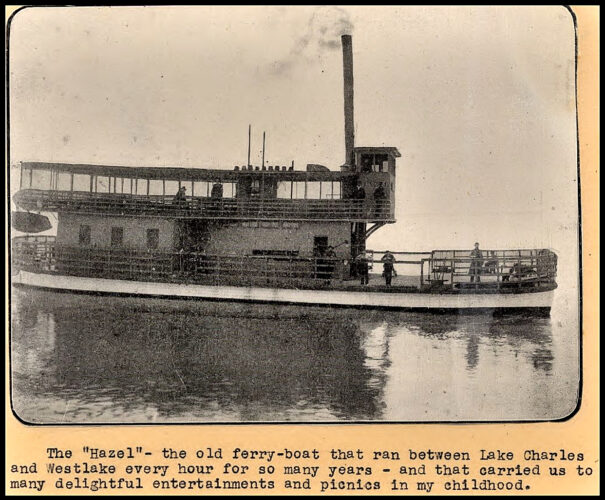

But I’d rather imagine the family being able to enjoy their first Sunday outing in pleasant weather, visit the lake, perhaps eating a few oysters while watching the pleasure boats come and go, a freight schooner or two, and the ferry Hazel keeping its hourly schedule to and from the west side of the lake. This was a time of excitement and optimism, and the Champagnes had no idea that job losses and financial hardship were in their future. Maybe one of the older kids asked J Euclide if they could take a little ferry ride out on the lake, and he may have considered it. But finding out it was 30 minutes to Westlake and 30 minutes back, with a sleepy 2-yr old in tow, he might have deemed it an activity best saved for another Sunday.

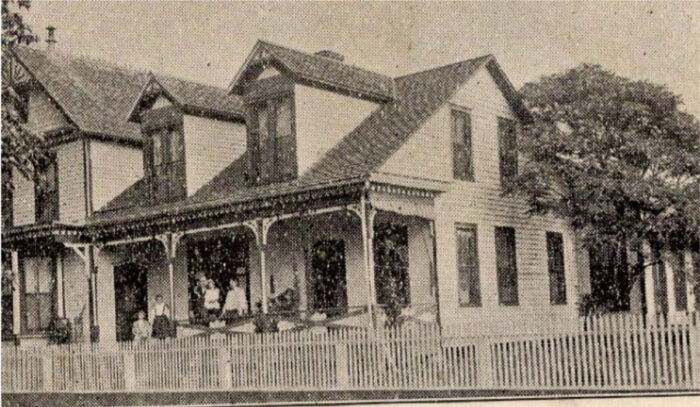

Instead, I imagine them simply walking home, ending their first Sunday outing with a walk home by way of the grand homes and mansions of Broad St. They wouldn’t have known anything about the seafaring immigrants from the Danish Foehr Islands, seeking peace, as with other Europeans, from political or religious strife. They wouldn’t have known anything about the early American pioneers down from up north and east, sometimes taking several generations to do it, eschewing established towns in favor of the fresh pioneer experience , or the ‘Michigan Men’ lumber barons from the north whose success would find expression in the architecture of Broad St. They would simply see faces, families, on their one day to be free from work, joining together with extended family, much as they did in Cajun country, laying out long tables under the oak trees after all going to church together. Only on Broad St, the in-laws would be catching up on each others’ week on wide expansive porches with enough rockers for big gatherings, and cousins playing on the lawn in clothes that didn’t routinely touch bayou mud or farm dirt. Only in these houses, the Champagnes would see Grandmère rocking on the porch with the rest instead of sweating in the hot kitchen, because money that paid for houses such as these also paid for cooks and housekeepers to manage a gathering of several generations across several households that routinely had 7-10 children each, all while periodically bringing trays of tea or lemonade with chunks of ice out to the porch.

So when they were done exploring the shoreline, they’d turn right and head home by way of Broad St.

~~~~~~~ cont’d on next post ~~~~~~~

================================================================================

[for my own organization – Church and town center – 20 screen pages, 42 shots]