.  The family folklore was that my grandfather had given it to my grandmother in 1910, which would have made her only 9 at the time. Its style, though, speaks of 1930s Taxco, a village in the mountains of central Mexico that gained both prosperity from the silver mines on which it sat and artistic renown for the silversmiths who mastered the art of working the mineral. Its 925 stamp says Taxco, but no year.

The family folklore was that my grandfather had given it to my grandmother in 1910, which would have made her only 9 at the time. Its style, though, speaks of 1930s Taxco, a village in the mountains of central Mexico that gained both prosperity from the silver mines on which it sat and artistic renown for the silversmiths who mastered the art of working the mineral. Its 925 stamp says Taxco, but no year.  It lay on my arm for 9 years through wild college years, chemically-enhanced adventuring and torrid romances, until I married a law professor who taught summer school classes in Mexico, when I got to see Taxco for myself. It was a thriving, postcard-picturesque little village which differed dramatically from other Mexican towns, so many of which were strapped by economic hardship or stripped of their cultural authenticity by their dependence on the insufficient tourist dollar. One afternoon’s walk up the narrow, winding cobblestoned roads put us in the path of a wedding procession ambling happily toward the church back down in the main zocalo, Santa Prisca, a beautiful 1750s Spanish baroque marvel built in thanks for the prosperity brought by the mine that lay beneath.

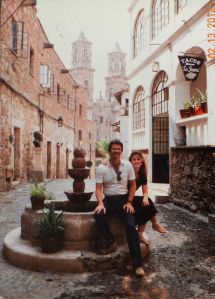

It lay on my arm for 9 years through wild college years, chemically-enhanced adventuring and torrid romances, until I married a law professor who taught summer school classes in Mexico, when I got to see Taxco for myself. It was a thriving, postcard-picturesque little village which differed dramatically from other Mexican towns, so many of which were strapped by economic hardship or stripped of their cultural authenticity by their dependence on the insufficient tourist dollar. One afternoon’s walk up the narrow, winding cobblestoned roads put us in the path of a wedding procession ambling happily toward the church back down in the main zocalo, Santa Prisca, a beautiful 1750s Spanish baroque marvel built in thanks for the prosperity brought by the mine that lay beneath.

.

.

The bracelet sat undisturbed on my arm for another 25 years, through a second round of graduate school and into a second marriage, until Hurricane Katrina. While gutting my sister-in-law’s house, it flew unnoticed off my arm with one of the many loads of rotted beams and moldy plaster that I pitched out on the street. Bobcats, those little hydraulic backhoes, were working overtime to take away the Katrina debris from in front of people’s houses as fast as they knew another one would appear. That night in the shower before bed, I first noticed Muna’s bracelet was gone, and I wept. How many people had told me I shouldn’t wear something so precious to me everywhere like I did. I prayed that if I got there the next morning early enough, I would beat the bobcats. But, no; the debris pile of the day before was again a perfectly flat, cleanly-scraped patch of dirt. Only one little imperfection broke the otherwise perfect, table-flat surface of the ground, and on closer inspection, it was one of the two tips of the bracelet. The half nearer the ground had been somewhat flattened, but it bent back into its semi-circle without breaking. Of all the loads it took that bobcat to load that day’s pile into the garbage truck, that bracelet was the only thing that was left behind.

Every day since, it has been on my arm. But the bend in that buried half grows weaker and weaker, splitting at the edges with every pull and tug until now only an inch of the inside silver sheet connects the two sides. No jewelry store will get near it. Update: January 2014, several 2-inch lengths of snipped coat hanger wire bent and stuffed in the cracks, then filled with J.B. Weld and clamped tight, and she’s solid as a rock.