I inherited some very special things that belonged to my great-grandmother which are gonna take some doing to go through and document. Alot of history and a few family mysteries are involved, and I think some research on Ancestry.com might be in order. But I’ll just start with photo studies and trust that the pieces themselves will tell me what they want me to do with them. One thing I do know; these aren’t pieces that get glued or wired to something else. They will probably go into a still life on a bookshelf, much like I did Tisolay in Turquoise and Black, with an assemblage of photos and documents, possibly behind a plexiglass sheet to keep dust out, or a display box that can be locked as well.

The only thing I knew about my grandfather’s mother when I was growing up in the 60s were the things of hers that Tisolay, my grandmother, would show me… beautiful things, things of a fine Victorian woman. My grandmother would take them out for me to see every once in a while, and to hold if I were very very gentle with them. She spoke of Mama Sitges, her mother-in-law, with so much love, as though she had been a well of good-natured acceptingness, ever patient with the sheltered new bride that her only son had brought to live with them. This is exactly how I would describe my Granddaddy, who must have been very like his mother.

.

Her silver brush and mirror were like nothing I had ever seen before. I assumed the beautiful woman with the flowing hair was her, Granddaddy’s mother, the woman with the monogrammed initials “ES”. Tisolay had a fine repousee vanity set, in Gorham’s Chantilly pattern, which she used every day, but not these. On those times when she took Mama Sitges’ brush and mirror out for me, she just held them with a special reverence, maybe passed the brush a few times over my long hair, but I never saw her use them herself.

Tisolay said that the “E” stood for Estelle, but that the “S” could have been for either Sitges, or her maiden name, Sabatier (or Sabater, she wasn’t sure, though she always pronounced it like the French would Sabatier, Sa-ba-chay). She just remembered something about her marrying relatively late in life. Growing up with these pieces, I often wished that I could picture the face in the mirror when Estelle first sat down at her dressing table to brush her hair, inspecting it in the mirror as she did so, and it frustrated me that the monogram couldn’t help me envision whether the face looking back were that of a young girl, a young single woman, or an older married woman.

I was further frustrated by not knowing whether there were an “i” in her last name or not… Sabater vs Sabatier…, which made a huge difference to me as it meant the difference between Granddaddy’s mother being French or Spanish. When I was in my 20s and doing genealogical research at the library, I could not find anything on her. But that piece of the puzzle, at least, was solved when Granddaddy died, and Tisolay and I found among his papers his parents’ marriage license dated February 15, 1893 with his mother’s name written out; Sabater, a Spanish name.

.

Fast forward a couple decades to a few months ago, when I find Estelle in the online archives of Ancestry.com and discover the sad circumstances in her childhood. (See Henrietta, Rosello’s Tomb and Aunt Nans for the full results of this research.) Her father died at 35 when she was two (as did her baby brother 14 days later), in 1864, just after New Orleans had fallen to Union Forces, leaving a widow with 3 remaining children under 6 without a breadwinner in a city whose river trade, abandoned crops, jobs and money had dried up like dust in the wind. Taken in by distant relatives, they never again lived in a home that was their own. It was hard to envision the “S” on Estelle’s brush and mirror standing for the Sabater of her early life; how could her family have afforded to give her a fine set like this when she was young.

Further helping to paint a time line in my mind for Estelle’s dresser pieces (rightly or wrongly) was a smaller brush in the identical style with a child’s face that I had always thought of as part of the set, but later noted did not share the same unique pointilistic style of monogram. The “S” on the child’s piece was in the more standard Old English style and seemed more machine made. This could only have represented the arrival of my Granddaddy, Estelle’s only child Percy. I could imagine the adult pieces being wedding presents, and the monograms being ordered by the giver in a grand style befitting a wedding present, and the child’s piece being bought soon enough afterwards for the same style to still be in vogue and in shops, being ordered by a young family just starting out. A google of the Art Nouveau style tied it in the proverbial bow for me. It came into vogue around 1890, when Estelle was around 30, and she got married and had her only child Percy, my Granddaddy, in 1893 and ’96, respectively. And with that, a few dry bits of archival data breathed life into a 120 year old piece of cold silver, putting a warm, flesh-and-blood face in the mirror of a 30 year old woman, a newlywed, with the dark hair and eyes of a Spaniard.

.

Another thing of Mama Sitges’ that Tisoleil used to show me when I was little, carefully unwrapping it from a box of old yellowed tissue, was a set of lace pieces. She told me it was Belgian lace, but at 4 or 5, I knew nothing about the hundreds of little bobbins that were woven under and over to create something like this. She told me it was a collar and cuffs, which puzzled me, being out of context from what they were supposed to go with. It made more sense to my young mind to see them as works of art in and of themselves, like the beautiful things we saw on our visits to Granddaddy’s museum. Such a staple of Victorian womanhood, they seem to me now.

Curiously, there was a small travel clock, in a leather case that looked like a Gothic triptych, whose most beautiful side was the face that no one saw, unless you took the clock out of the little case. Ti never told me anything about it, and I’ve had no luck googling what few markings are on the piece.

Also curious was something of Mama Sitges’ that Tisolay must not have liked, a mantle clock and two side statuettes, whose existence I was barely aware of. The heavy mantle clock was always up in the attic, broken, ignored and covered in dust. The two statuettes fared a bit better, kept on top of the kitchen cabinets, way up near the ceiling where they got coated in kitchen grease. I never took a close look at the clock until after Granddaddy died and we were up in the attic cleaning stuff out. It was heavy in both weight and appearance, and I could see why Tisolay, a lover of delicate things, didn’t like it.

I did, though, and recently I sent a picture of the set to the online site of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors and found out a little about it. It’s stamped Nich.Muller’s Sons on the back of a central seated figure made of pot metal that has corroded to a bumpy surface, its original finish, probably a faux bronze, long gone. The clock casing is similarly of pocked pot metal. The heavy iron base has most of its original black enamel finish intact, though thinly veiled in rust all over.

Nicholas Muller was from Koblenz, Germany, and in his 30s when he started a clockmaking business out of New York around 1850. He died in 1873, and from then to 1890 when they went out of business, the business was known as Nicholas Muller’s Sons, which dates the clock between the years 1873 and 1890. The central figure is Ivanhoe. Another clockmaking company, often affiliated with Muller, was Ansonia, which frequently cast Fisher and Falconer figurines like these as companion pieces to Muller’s clocks, though there are no identifying marks of any kind on mine. In 1893, when it might have been given to Estelle Sabater as a wedding present, it cost between $28 and $40. As today’s salaries are roughly 100 times what they were then, this clock would cost, today, $2800 to $4000. Just the clock, not including the side statuettes. If they went out of business in 1890, would their clocks still have been in stores in 1893? Did J. Henry Sitges ever make the kind of money that would permit him to buy such a clock for Estelle when he never bought her a home of her own?

I have other evidence that points to the likelihood that Granddaddy’s ‘Aunt Nans’ may have been the clock’s original owner, and that Mama Sitges had simply inherited it with Aunt Nans’ other possessions when she died. Nans was very close to Mama Sitges’ family, living with them since before Granddaddy was born until her death when Granddaddy was 23. She and her husband, a successful cigar maker, had never had children, or the expenses associated with raising a family. Had the clock been hers? Had her family been well-to-do? Henrietta, Rosello’s Tomb and Aunt Nans goes further into the mystery of Aunt Nans.

Alas, all I know is that at the end of Mama Sitges’ life, in the early 1930s, it had been hers, and had gone to her son Percy when she died.

___________________

.

Recently, when I found Estelle in the archives, my love of ancestry caused me to celebrate what I found to be a rather unique Old World Spanish Island heritage. Her mother, Estelle Pino, was from a family of Canary Islanders who’d immigrated to Louisiana two generations before in the 1780s. The Canaries being in the Atlantic off the African coast of Morocco and Western Sahara, they were the last supply stop for Spanish ships bound for their New World colonies, important for their easterly winds. Her father, Juan Sabater, a New Orleans cigar maker born in Cuba, was from a family who’d immigrated to America around the same time as the Pinos from the Balearic Island of Menorca. Situated in the Spanish Mediterranean just about due east of the coastal town of Sitges on the mainland, which is of course my Granddaddy’s name, it boasted a port city which had been colonized all the way back through the Carthaginians to the Bronze-Age Minoans. I had already traced Granddaddy’s father’s line to Menorca as well. So when I saw not only that both Granddaddy’s parents had Menorcan ancestry, but that they’d both arrived to New Orleans in the same year, 1835, it painted a picture of immigrant strangers finding each other and forming close-knit social circles and commercial networks that kept their shared Old World culture alive.

But nothing Granddaddy ever said about his mother or his childhood had anything to do with being Spanish in their day-to-day life; no language use or anything, either on her part or his own, so I couldn’t help wonder how much that heritage played a role, if at all, in how Estelle saw herself and the world around her. Just as before, though, the archives I recently found shed light on circumstances that could be of relevance.

While Estelle’s father’s family, the Sabaters, stayed within the Spanish influence of first Florida, then New Orleans, her mother’s family, the Pinos, had settled the ill-fated town of Galveztown upriver, whose surviving settlers eventually dispersed into the part of Louisiana ceded to England, around Baton Rouge, a British-settled, English-speaking, Protestant town. Two generations removed from her Old World Spanish roots, she gave her children names that tell more of which culture might have held sway in the Sabater household had her husband’s death not disrupted things so suddenly. Her first child, born 2 days before Christmas in 1856, she named Victoria. Victor followed in November of 1858. Her second girl she named for herself, Estelle, born on March 9 of 1862, but it was back to the British royalty 19 months later for her second son, named Albert, born in October of 1863. Mother Estelle was widowed, however, the following year and did not get to head her own household after that. Her husband’s Menorcan network of family and friends, which she and her small children were swept up by, must have been all around them, because at least one of the grown daughters of the Garcias who took them in was married to a Menorcan immigrant, Pedro Rosello, and her own daughter Victoria grew up to marry a Menorcan, Bartolome Pico, both of whom had lived and worked only a block from where her husband had made a home for his wife and children. Eventually, of course, little Estelle herself would marry the son of another Menorcan immigrant, Francisco Sitges, my great-grandfather Jerome Henry Sitges. I can’t find the Garcias’ origins, but I’d be surprised if they weren’t Menorcan and somehow related to the Sabaters, though it’s possible they could have been related to Estelle Pino’s Canary Islanders. Tight-knit bunch indeed, the Menorcans of New Orleans. Let’s hope that this helped buffer little Estelle and her family from the politics, corruption, and racial violence of the times, because Estelle’s first 15 years of life put her smack in the middle of Louisiana’s vicious Reconstruction era.

Still, nothing Granddaddy ever described about his mother hinted at a Menorcan awareness or Spanish ethnicity of any kind, or sounded like anything other than what a traditional English/American Victorian woman would be.

_____________________

.

Except, of course, her Catholicism.

One of those days after my Granddaddy died, when Tisolay and I were up in the attic going through the things in an old trunk of his, we came across a small tin box. In it, together with some holy cards from when he made his Confirmation at 13, in 1909, each one wrapped in brittle yellowed wax paper, was a scapula which was dated 1877, no doubt his mother’s when she would have been 15. It was traditional for Catholic women to pin a scapula to the inside of their clothes, and it’s easy to see where this one had been pinned.

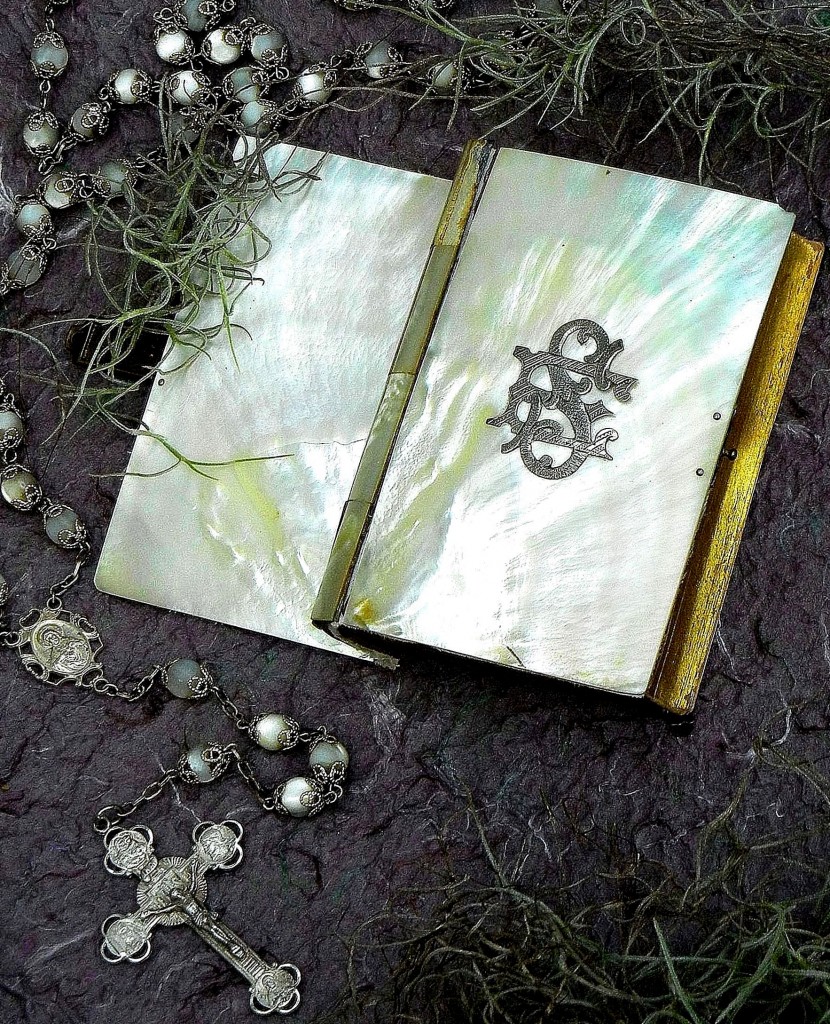

Also in the box belonging to Estelle was a small missal with silver initials “ES” that were attached to the cover, something which took my breath away when I unwrapped it, but nothing compared to when I got it out of the dark attic and into the sunlight. The cover was of abalone mother-of-pearl, one solid piece, and judging by how slight the convex bowing of the shell was, the abalone would have to have been of a size like we don’t see too much anymore. It was published in 1884, when young Estelle was 22.

.

.

Mama Sitges’ rosary was also mother-of-pearl, but Tisolay used it regularly and, sadly, it had been cleaned with something it shouldn’t have, sanding off the polished finish.

.

.

____________________________

.

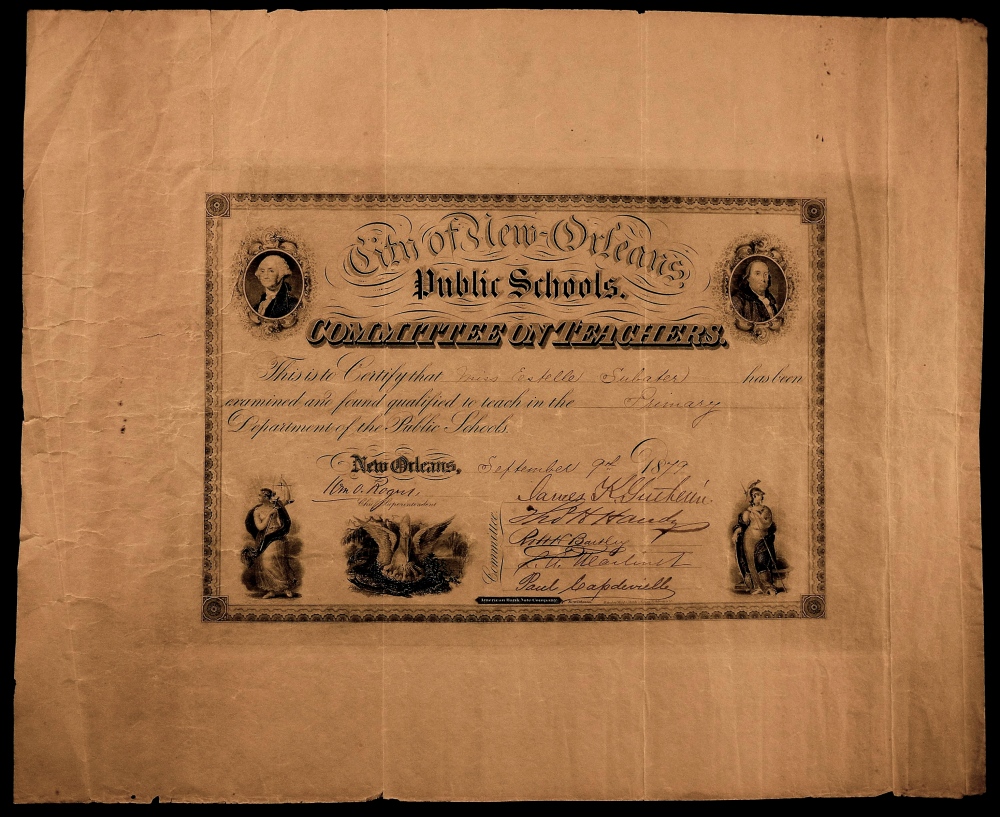

Estelle graduated high school in June of 1878, and while this and a teacher’s certificate she earned the following year are all I have of her at this age, Ancestry.com went a long way with its census records and directories toward giving me a picture of what Estelle’s 15 years of unmarried life was like. It was a time of change for the Sabaters. Four months before Estelle’s graduation, older sister Victoria got married, and after a year or so, took her mother and siblings with her to live in her new husband’s home. Estelle had grown up in the home of Henrietta Garcia >>>, a big family compound on Claiborne and Common St. that served as both headquarters for the family cigar-making business, and residence, where the widow Henrietta Garcia and her oldest son Charles, head of the business, had not only taken care of 100 yr old patriarch Carlos and the last of Henrietta’s unmarried girls, but also Estelle Sabater and her 3 children, who were roughly 10 years younger than the Garcia girls.

.

.

Later, in 1874 when little Estelle was 12, Charles, by then the only one left in the big family compound, moved to a smaller place a few blocks away, taking the Sabaters, who must have been like family by then, with him.

Soon after Charles and the Sabaters vacated the Garcia house, Henrietta’s oldest daughter Cecilia and her husband Pedro Rosello, a Menorcan cigar maker who’d immigrated nearly 30 years before, decided to move in and open a new store closer to the Garcia house. At 36 and 47, still childless after 8 years of marriage, they left behind the cramped, noisy, increasingly dilapidated French Quarter and their life above Rosello’s corner cigar store on Bienville and Exchange, for the Garcia/Sabater’s neighborhood, little suspecting that they would soon be trading places with the Sabaters. One of the French Quarter neighbors that Cecilia and Pedro were leaving behind was Bartolome Pico, a carpenter also from Menorca who’d immigrated the year after Rosello had and opened a coffee house one block from Rosello’s old corner cigar store. It would have been on the first floor of a several-story brick building with residential apartments above the store, typical of the architectural style of the day. Both Pico and Rosello had lived and worked a block from the Old Levee St address where Juan Sabater and his young family had, making what may have been a little Menorcan enclave at the southern corner of the Quarter. Pico and Rosello had both immigrated around 1853, and all 3 were nearly the same age, but whether they knew each other is anyone’s guess. Two years after the Rosellos moved out of the French Quarter, 21 yr old Victoria married Pico, who was by then a widower of 45, and went to live with him above his coffeehouse-turned-saloon in the Quarter together with his grown son and brother-in-law from his previous marriage.

The widow Estelle, with young Estelle and Victor, now grown and the family breadwinner with a job at a household goods store, bid goodbye to Charles L as well, no doubt with heart-felt thanks… (in fact, one of Victoria and Bartolome’s sons would bear the name Charles Lewis in his honor)…, and then moved into a temporary apartment while Victoria’s husband prepared an apartment for his new in-laws above the saloon. Whether Pedro and Cecilia were close enough to the Widow Estelle to have played a role in introducing Pico to the Sabater family living with her brother Charles a few blocks away is also unknown, but the temporary apartment the Sabaters went to was the same building as Pedro’s new cigar store. By 1880, the census finds the Sabaters all together again with Victoria and her new husband in the French Quarter, one of 3 households living above Pico’s saloon; the first being Bart, listed as a dealer in liquor, Victoria, and his grown son and brother-in-law from his first marriage, clerk and bartender respectively; the second being a trio of men listed as boarders, and the third being Widow Estelle, young Estelle and Victor.

I can’t imagine this being a very genteel, civilized household, but Victorian men being very formal and proper, and Spaniards even more so, who’s to say Pico’s place wasn’t a fine gentlemen’s establishment. Certainly nothing like the wild bars of Galatin Alley down by the French Market at the docks where fighting Irishmen and river boatmen, with fresh paychecks in hand from the long haul down the Mississippi, looked for women and trouble with a whiskey in one hand and a gun in the other.

However it was, such was what greeted young Estelle, together with her mother and brother.

.

The year after graduation, young Estelle went on to get her primary school teacher’s certificate, and by 19, could relinquish the title of youngest in the family to Victoria’s little 18-month-old, Lawrence Gaetano Pico. I can’t find anything about where Estelle taught, and the 1890 census, with its wealth of data, is missing. All I know is that she continued to live with her family.

The year 1893 was not only the year Estelle married my great grandfather J. Henry Sitges, but the year the Sabater/Pico clan is first listed in the directory as having moved to Foucher St which was, in effect, in the suburbs, just up river from the elegant Garden District. It represented a real change of pace for them, where homes were set back from the street and surrounded by open expanses of trees, yards and gardens; a more pastoral neighborhood that had once been the separate town of Jefferson City before being annexed by New Orleans. In 1894, Pedro Rosello died, and Cecilia came to live with them, making 3 widowed women running a household together; her sister Victoria at 37, “Aunt” Cecilia (as censuses from this period listed her) at 54, and her mother Estelle at 63. Estelle had married a man whose business interests, being in Mexico and Central America, would take him away from home for long periods of time, so for safety and company, it came to be that she never left the house of these women and would never be mistress of her own household.

The Sabaters lived with the Picos in the French Quarter for a decade until late 1890, when Bartolome Pico died and the Sabater/Pico women moved back to the Garcia’s Claiborne neighborhood with Victoria’s 5 children in tow, and brother Victor, a crockery salesman who never married. The following year, a 30-yr-old New Orleans businessman who had just returned from a long period of work in Panama listed his address as 19 Old Levee, the house where Juan Sabater had spent his last years with his young family 31 years before. His name was Jerome Henry Sitges, and on Feb.8, 1893, he married Sabater’s youngest daughter Estelle, who was also 30; a late marriage for both of them. It is interesting to me, this convoluted mystery of who knew who when, and trying to figure out the extent of any pre-existing relationship between the Sabaters and the Sitgeses. If Mother Estelle had been financially strapped enough after Juan’s death to have to live with relatives, is it likely that Mother Estelle would still own the 19 Old Levee property, and meet her daughter’s future husband by being his landlord? I wouldn’t think so. Perhaps she did still own it, rented it for income, and went back home to live with her mother and brother simply because she had a baby son that her mother wanted to help with. Did they meet for the first time as landlord and tenant of the Sabater house at 19 Old Levee? Or did they already know each other? Back in 1852, Bartolome Pico had immigrated to America aboard a ship that also carried two Taltavull sisters from Menorca, one of whom would become J Henry’s mother. The Taltavull sisters would each marry Sitges brothers, Marcos and Francisco, J. Henry’s dad, and all 5 of them, counting Pico, were from Menorca. Had the Sitges and Sabater families known each other before J.Henry and Estelle were married? If the Widow Estelle did own the house, was it too small for her to take in boarders for income? Or was it just sublime coincidence that these two men, 31 years apart, rented the same property?

.

The scope of this blog page is supposed to encompass only the unmarried years of my great-grandmother Estelle’s life, ending in 1893, the year she married and the year the extended Sabater family moved out of the French Quarter to the Foucher St house. But since I don’t have a picture of her before her marriage, I will leave you with the earliest photo I have of her, my favorite of the several that I found among Granddaddy’s papers after he died.

That patience and calm that Tisolay had seen so much of in Mama Sitges, and I have always seen as so central to the nature of my sweet Granddaddy? The face in the mirror, with 11 years added to it? I think this wonderful portrait captures it; nails it to a wall!

.

.

. This is a companion piece with Henrietta, Rosello’s Tomb and Aunt Nans

.

.