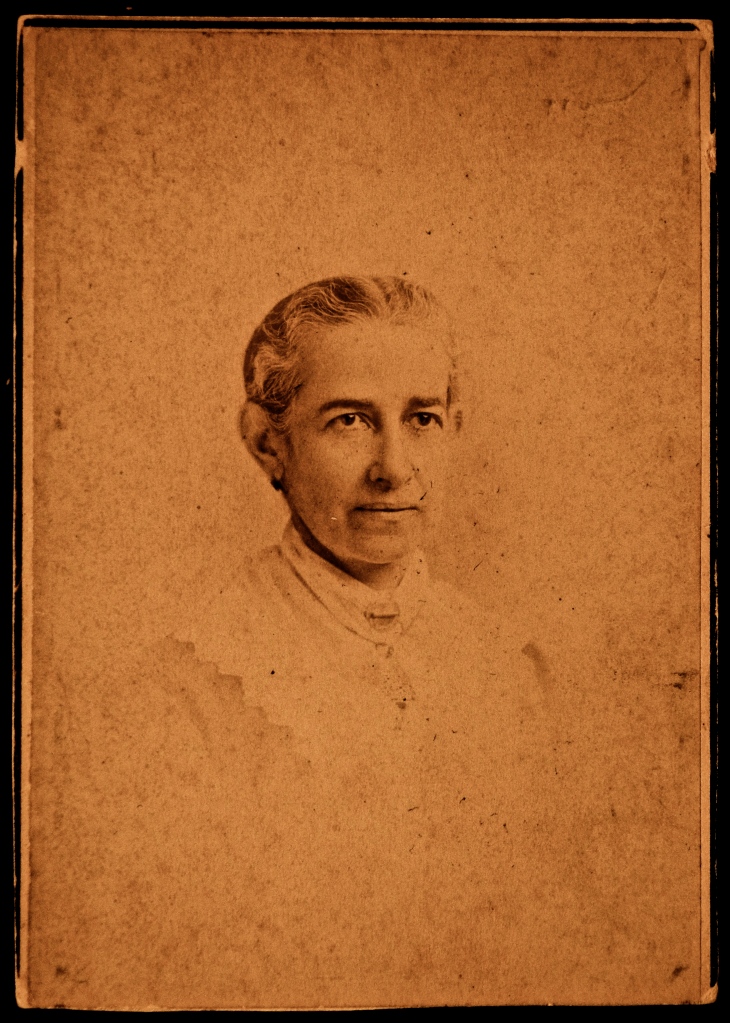

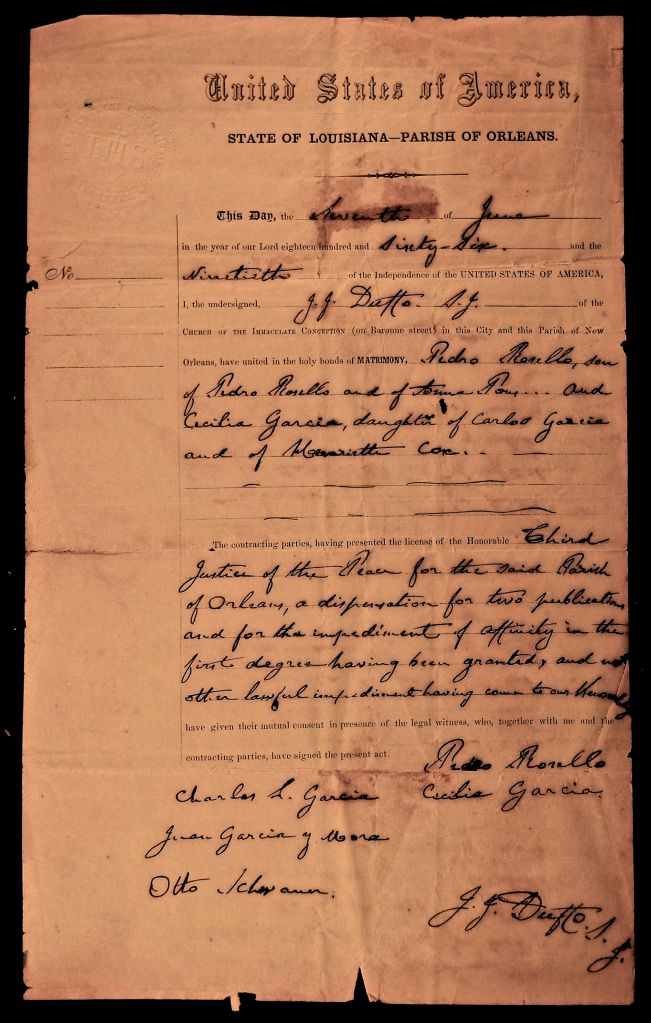

. Henrietta . In with my grandfather’s papers is an old photograph, a formal portrait, of an elderly woman I don’t recognize as any ancestor I’ve been told about. My interest in the family history did not arise until my grandfather was already gone, and all my grandmother knew was that her name was Henrietta Cox, and something about her not having any children. Tisolay always used to say that Granddaddy had been raised by an “Aunt Nans”, though his only aunt’s name was Victoria. We also knew that the home he was raised in was run by his Aunt Victoria, a widow, and his mother Estelle who lived like a widow in that her husband spent a great deal of his time in Central America and Mexico where he had several business interests, including a book binding business that printed some of Mexico’s paper money, stocks and bonds. We didn’t know who Aunt Nans was, but it wasn’t Aunt Victoria, and Tisolay seemed sure that she wasn’t the woman in the photograph. I found Henrietta’s name, though, years later, on one of the many old family parchments that have survived for over a century to end up in my hands when Tisolay and Granddaddy died, a marriage document from June of 1866 where Henrietta Cox was the mother of the bride. (So much for her not having any children.) This didn’t give any hint as to how we were related, though. What it did was scratch the itch of another family mystery. . Pedro Rosello’s tomb . The older of our two family tombs in the Garden District’s Lafayette Cemetery, the one that holds Victoria and Estelle Sabater, the latter being my great-grandmother, has a name at the top, etched large into the masonry, that none of us has ever recognized. Pedro Rosello, the tomb says, was born in 1828, on the Balearic Island of Menorca, and died in New Orleans on Nov.12, 1894, age 66. I knew that the Sitges family had also come from Menorca, but neither Tisolay nor I knew of any relatives with that name, and neither of us knew how we came to be buried in his tomb. I had always figured that we had bought the tomb from someone who ended up not having any descendants in the city. Whoever he was, though, Pedro Rosello was the name on the marriage document of the groom who married the daughter of Henrietta Cox, the woman in the photograph.

. Henrietta . In with my grandfather’s papers is an old photograph, a formal portrait, of an elderly woman I don’t recognize as any ancestor I’ve been told about. My interest in the family history did not arise until my grandfather was already gone, and all my grandmother knew was that her name was Henrietta Cox, and something about her not having any children. Tisolay always used to say that Granddaddy had been raised by an “Aunt Nans”, though his only aunt’s name was Victoria. We also knew that the home he was raised in was run by his Aunt Victoria, a widow, and his mother Estelle who lived like a widow in that her husband spent a great deal of his time in Central America and Mexico where he had several business interests, including a book binding business that printed some of Mexico’s paper money, stocks and bonds. We didn’t know who Aunt Nans was, but it wasn’t Aunt Victoria, and Tisolay seemed sure that she wasn’t the woman in the photograph. I found Henrietta’s name, though, years later, on one of the many old family parchments that have survived for over a century to end up in my hands when Tisolay and Granddaddy died, a marriage document from June of 1866 where Henrietta Cox was the mother of the bride. (So much for her not having any children.) This didn’t give any hint as to how we were related, though. What it did was scratch the itch of another family mystery. . Pedro Rosello’s tomb . The older of our two family tombs in the Garden District’s Lafayette Cemetery, the one that holds Victoria and Estelle Sabater, the latter being my great-grandmother, has a name at the top, etched large into the masonry, that none of us has ever recognized. Pedro Rosello, the tomb says, was born in 1828, on the Balearic Island of Menorca, and died in New Orleans on Nov.12, 1894, age 66. I knew that the Sitges family had also come from Menorca, but neither Tisolay nor I knew of any relatives with that name, and neither of us knew how we came to be buried in his tomb. I had always figured that we had bought the tomb from someone who ended up not having any descendants in the city. Whoever he was, though, Pedro Rosello was the name on the marriage document of the groom who married the daughter of Henrietta Cox, the woman in the photograph.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

June 7th, 1866 – Parish of Orleans, Louisiana – Marriage . . . PEDRO ROSELLO, son of Pedro Rosello and Anna Pons, and CECILIA GARCIA, daughter of Carlos Garcia and Henrietta Cox . . .

. . . . a dispensation for . . . the impediment of affinity in the first degree having been granted . . . .

Witnesses – Charles S. Garcia . . Juan Garcia y Mora . . Otto Schwaner

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

Wait. What? “An impediment . . . of the first degree”? He married a woman in his immediate family ???

Okay. . . . So Henrietta had a husband, Carlos Garcia . . . and they had a daughter, Cecilia . . . who got married in 1866 to Pedro Rosello… who was a member of their immediate family? Cousin, maybe, but what Oedipal twitch in the mind of the notary made his quill pen write out ‘first’ degree, instead of ‘second’ or ‘third’? Amused no end, I delighted in the scandalous overtones until I remembered that Impediment of Affinity meant relatedness by marriage, not blood, which was called Impediment of Consanguinity, and that for some reason, the two were equally illegal back then. Not as much fun, and still no closer to the mystery of who Pedro and Henrietta were to us, it did, however, serve to solve another, that of Cecilia’s death.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . MRS. PEDRO ROSELLO (born GARCIA), native of New Orleans . . . age 22. . . .died on March 21, 1865 . . . corner Bienville and Commercial alley. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . She died in 1865? I have her marriage document from 1866! An intrepid girl, our “Mrs. Rossello-born-Garcia”. And why, when her life was over, was her own name completely taken from her, leaving only the names of the men in her life? That gives me the creeps. . . Ynez . The riddle of her death, though, is solved by the riddle of her marriage. If Pedro and Cecilia’s marriage represented an affinity of the first degree, by marriage, then he would have to have had a pre-existing relationship with someone in her immediate family, and not a blood relationship. Was this his second marriage into Henrietta’s family? Did Cecilia have a sister who would have been 22 in 1865, like the girl in the death certificate? Census records are a wealth of data that breathe life and paint faces onto black and white words on a page, and a click of a button on the Ancestry.com website brought me to the 1850 New Orleans census. Carlos Garcia, 65, was a cigar maker born in Spain, and Henrietta Garcia, 35, was from Missouri and called Harriett. They lived in the 1st ward of the 3rd municipality, today’s Faubourg Marigny immediately downriver from the Quarter, and had 1 boy and 4 girls between ages of 13 and 1. Cecilia was the oldest girl at 11, which means that in 1865, she would have been 26, not 22. Her next younger sister, though, was 7, which would have made her 22 the year Pedro Rosello’s wife died. She appears again in the 1860 census, but then disappears from the record. It is common for records to have been lost to fire or flood, or simply to a misspelling in the records. But for a person to completely disappear from the record? This death certificate wasn’t Cecilia’s. It was hers, the girl with no name, who ceased to be either Mrs. Pedro Rosello or Miss Garcia on that crisp spring day in March of 1865, on the corner of Bienville and Commercial alley. Dead at only 22, in March, a little early in the year for the Yellow Fever that routinely took so many lives during the mosquito-ridden New Orleans summers. Did you die in childbirth? The census doesn’t tell me. What it does do, though? It gives you back your name.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . MRS. PEDRO ROSELLO (born GARCIA), native of New Orleans . . . age 22. . . .died on March 21, 1865 . . . corner Bienville and Commercial alley. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . She died in 1865? I have her marriage document from 1866! An intrepid girl, our “Mrs. Rossello-born-Garcia”. And why, when her life was over, was her own name completely taken from her, leaving only the names of the men in her life? That gives me the creeps. . . Ynez . The riddle of her death, though, is solved by the riddle of her marriage. If Pedro and Cecilia’s marriage represented an affinity of the first degree, by marriage, then he would have to have had a pre-existing relationship with someone in her immediate family, and not a blood relationship. Was this his second marriage into Henrietta’s family? Did Cecilia have a sister who would have been 22 in 1865, like the girl in the death certificate? Census records are a wealth of data that breathe life and paint faces onto black and white words on a page, and a click of a button on the Ancestry.com website brought me to the 1850 New Orleans census. Carlos Garcia, 65, was a cigar maker born in Spain, and Henrietta Garcia, 35, was from Missouri and called Harriett. They lived in the 1st ward of the 3rd municipality, today’s Faubourg Marigny immediately downriver from the Quarter, and had 1 boy and 4 girls between ages of 13 and 1. Cecilia was the oldest girl at 11, which means that in 1865, she would have been 26, not 22. Her next younger sister, though, was 7, which would have made her 22 the year Pedro Rosello’s wife died. She appears again in the 1860 census, but then disappears from the record. It is common for records to have been lost to fire or flood, or simply to a misspelling in the records. But for a person to completely disappear from the record? This death certificate wasn’t Cecilia’s. It was hers, the girl with no name, who ceased to be either Mrs. Pedro Rosello or Miss Garcia on that crisp spring day in March of 1865, on the corner of Bienville and Commercial alley. Dead at only 22, in March, a little early in the year for the Yellow Fever that routinely took so many lives during the mosquito-ridden New Orleans summers. Did you die in childbirth? The census doesn’t tell me. What it does do, though? It gives you back your name.

Hello, Ynez. . . . .

Did you know that Granddaddy had a cousin named after you?

Below the name of Pedro Rosello on the family tomb, and the names of the two grown Sabater sisters below that, are the names of Victoria’s children, Granddaddy’s first cousins, Lawrence Gaetano, Victor Bartolome, John Albert, Charles Lewis, and my mother’s “Aunt Peetie”… Inez.

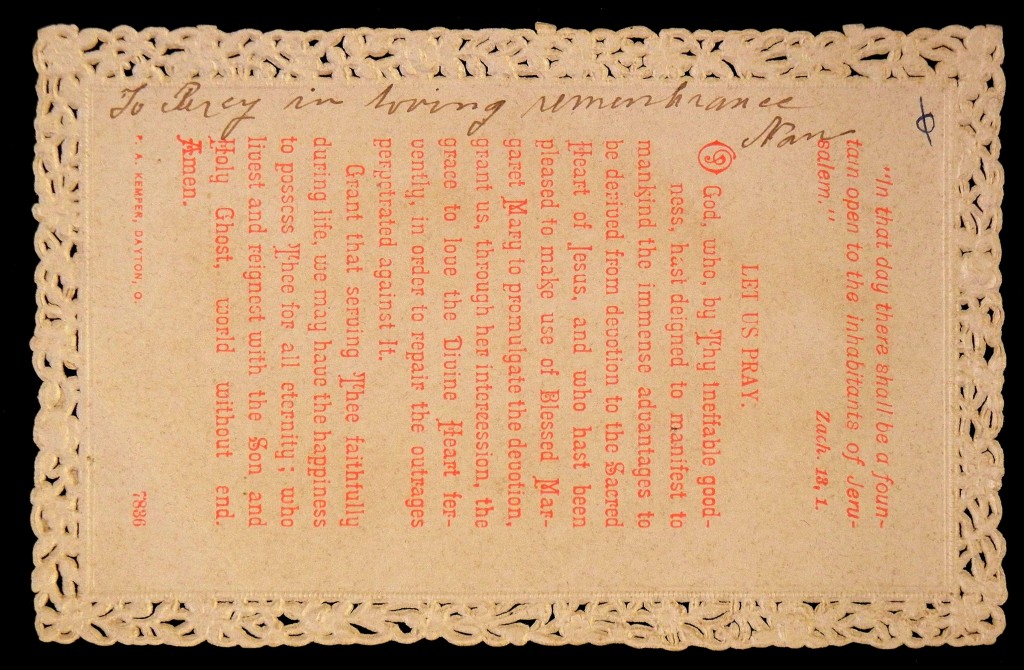

I have a holy card of little Inez’s from her First Communion, probably around 1900.

.

.

.

.

.

.

According to the tombstone, Victoria was only 3 years old when Inez “Rosello-born-Garcia” died, so she couldn’t have gotten to know her well enough to leave such an impression that she would name a child after her. Honoring an ancestor who died too young isn’t a stretch, though. But we don’t even know if the Sabater family knew the Garcia family. But then, that’s sorta what we’re looking for… how the Sabaters came to be buried in the Garcias’ son-in-law’s tomb.

.

___ (aside) ____

Something just occurred to me. Almost 30 years ago, when I dragged Tisolay into my epic project to clean the attic after Granddaddy died, we found a bunch of these First Communion holy cards in an old trunk of Granddaddy’s in the attic, wrapped in wax paper inside a small tin box, each one a masterpiece of intricate lace-like paper. Most of them were inscribed on the back with varying versions of “To Percy, April 15th, 1909”, some in pencil in a child’s handwriting, obviously from fellow students, and some from adults in penned script, such as those from his Rev. Mother and “Grandma”. The names of the givers didn’t mean much to me at the time. I knew Granddaddy had a cousin Inez, but didn’t know anything about her, and assumed that since her card was in with Granddaddy’s, that they had made their First Communions together.

There was another card whose significance I didn’t get until now, inscribed in an elegant adult hand, “To Percy in loving remembrance, Nan”.

Aunt Nans!

(I can’t help but smile at the little circle with a line through it, after Nan’s name. Anyone whose parents drummed Southern manners into them as a child will recognize the code indicating that the required thank-you note has been written and sent.)

.

_____(back to Rosello)_____

.

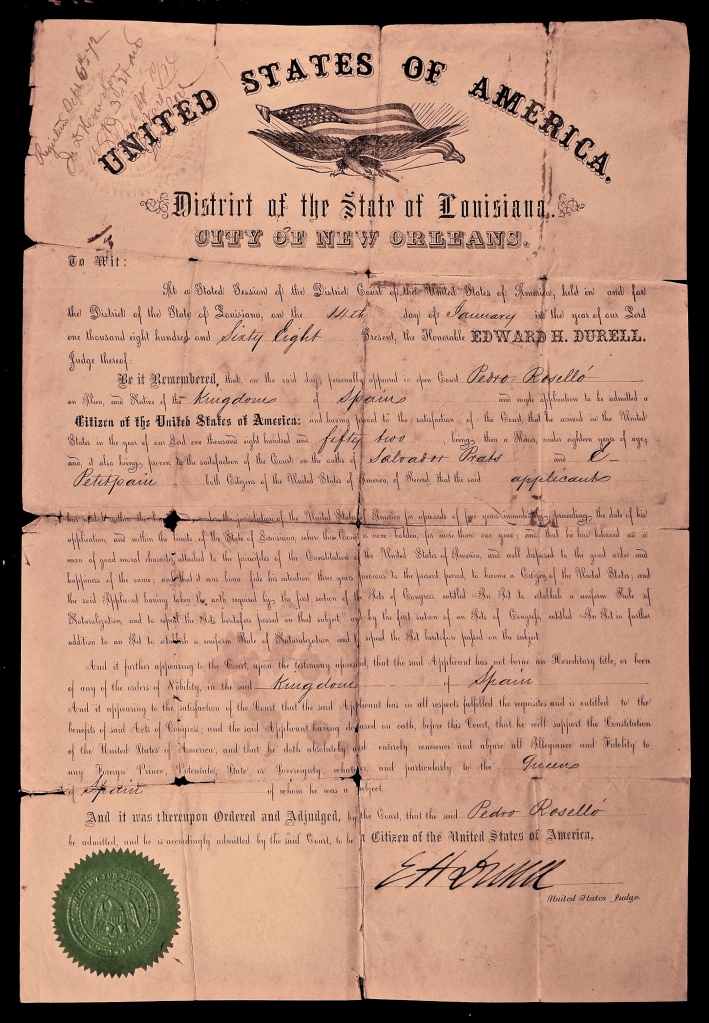

For a man we knew nothing about, there were certainly alot of his papers in with Granddaddy’s things. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . NAVY DISCHARGE – August 12, 1853 – Department of Cartagena, Province of Menorca “… PEDRO ROSELLO, son of another PEDRO ROSELLO and ANA PONS, native of Alayor, near Mahon… has graduated from his term of service in the Navy begun March 12, 1845…” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . From Menorca to New Orleans . Pedro’s discharge papers from the Provincial Navy of Menorca describe him as 25 years old, with a ‘regular’ face and body, brown eyes, and thin beard. He had joined the navy in Menorca when he was 17, and according to his citizenship papers, made his first trip to New Orleans in 1852, a year before he was discharged. After his discharge date, he made several trips to the Spanish naval headquarters in Havana through what seem to be a couple of short extensions of his service, each documented by a handwritten addendum on the back of his discharge paper. The last of these gives him leave to “return to his domicile in New Orleans” for good, in a manner that would suggest that he already had a domicile in New Orleans; had been there enough times to set up his new life here. In fact, when he first arrived in New Orleans, he quite possibly was met by his brother Diego, 6 years his senior, who had sailed from Menorca to New Orleans 5 years before. A few online clicks had found me an old ship list where Diego, a merchant of 25, had been a passenger aboard the schooner Primera de Cataluña out of Barcelona that put him ashore in New Orleans on Dec.1, 1847. Sailing from Menorca to the mainland, he’d caught a ship bound for America together with 35 other passengers who were nearly all from Menorca as well. The passenger manifest for the arduous 2 month voyage showed that most were in their hardy teens and 20s, a few in the 30s and 40s, with 15 of the 36 being women and children. Many were single men, but several had their wives and children on board, as well as a few grandparents and cousins. A 29-yr-old single woman, Marguerita Pons, may have been Diego’s cousin, his and Pedro’s mother being a Pons. And another passenger, Marcos Sitges y Mercadal, a 26 yr old carpenter who was my granddaddy’s great uncle, was traveling with 44 yr old Antonio Mercadal, an uncle or possibly an older cousin. Occupations varied. There were several tailors, several merchants, a farmer, a musician, a carpenter (M. Sitges), a smith, a hackler (combs flax fibers for spinning linen), a clerk, and 3 teenagers who listed themselves as students. Was this ocean voyage where the Rosello/Sitges friendship was first forged? Months of day-in/day-out proximity, sharing experiences of death, disease, hardship and tragedy, as well as friendship and love, every minute, 24/7, could easily forge new families and lifelong friendships. I could see that. The Sitges clan was from the port city of Mahon; the Rosellos were from the town of Alayor, 7 miles inland . Did they know each other before sailing to America together? Were there already family ties? . . . . Are the answers lost to the winds? . Menorcans in New Orleans . In November of 1854, a year after Pedro had settled for good in New Orleans, Juan Rosello y Pons, a year younger than Pedro, landed in New Orleans. The 3 Rosello y Pons brothers arrived on a wave of immigration into New Orleans that had already swelled the city to the 3rd largest in the United States and helped make its port one of the most important in the western hemisphere. Immigrants came from all corners where poverty or religious prejudice or political upset was felt… mostly Catholics… from French Canada and Spain’s Canary Islands, from Haiti, from Ireland and Germany, and to a smaller degree, the Balearic Islands. It made sense that Menorcans, who were not happy with the fact that Menorca had recently been transferred to the English throne, were more and more drawn to one of the most prosperous Catholic cities in America. The Menorcan population and culture was not like that of the traditional Spanish, Island Spanish, or even its fellow Balearic Islands. A Meditteranean island off the east coast of Spain, Menorca is only 25 miles from one end to the other but boasts one of the finest deep natural harbors in the Meditteranean, at Mahon. And because of this, it had been previously settled by Moors, Romans and Carthaginians around the time of Christ, and before that by the Bronze Age Minoans around 2500-1500 BC, all the way back to prehistoric peoples who left behind the famous Menorcan megaliths. Its culture was unique and separate from that of mainland Spain, as was their isolated Catalan dialect, and in this strange new America across the ocean, Menorcans sought each other out. . Pedro and the Bienville St. cigar shop . In 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, a New Orleans city directory was published. Pedro Rosello, by then 33 and in New Orleans for 8 years, is listed as a cigar maker with a cigar and snuff store on the corner of Bienville and Exchange Alley, in the SE corner of the Quarter, near the river and its Canal St. boundary. Canal St. was the ‘neutral ground’ that separated the squabbling French and Spanish Creoles in the Quarter from the ambitious American newcomers who came flooding into the city after Louisiana became a State. Refused entry into their insular Creole world, both physically and socially, the ‘barbarian Kaintucks’ were relegated to the relative wilds south of Canal St, which would soon outshine the old Quarter in business and wealth as the elegant Faubourg Ste. Marie. Such internal feuds and infighting probably didn’t concern Rosello, though, and while the old-line Europeans allowed him as a Spaniard to live and work among them in the Quarter, he listed his first name in the directory in the American style, in both spelling and by dropping the maternal surname of Spanish tradition.

For a man we knew nothing about, there were certainly alot of his papers in with Granddaddy’s things. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . NAVY DISCHARGE – August 12, 1853 – Department of Cartagena, Province of Menorca “… PEDRO ROSELLO, son of another PEDRO ROSELLO and ANA PONS, native of Alayor, near Mahon… has graduated from his term of service in the Navy begun March 12, 1845…” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . From Menorca to New Orleans . Pedro’s discharge papers from the Provincial Navy of Menorca describe him as 25 years old, with a ‘regular’ face and body, brown eyes, and thin beard. He had joined the navy in Menorca when he was 17, and according to his citizenship papers, made his first trip to New Orleans in 1852, a year before he was discharged. After his discharge date, he made several trips to the Spanish naval headquarters in Havana through what seem to be a couple of short extensions of his service, each documented by a handwritten addendum on the back of his discharge paper. The last of these gives him leave to “return to his domicile in New Orleans” for good, in a manner that would suggest that he already had a domicile in New Orleans; had been there enough times to set up his new life here. In fact, when he first arrived in New Orleans, he quite possibly was met by his brother Diego, 6 years his senior, who had sailed from Menorca to New Orleans 5 years before. A few online clicks had found me an old ship list where Diego, a merchant of 25, had been a passenger aboard the schooner Primera de Cataluña out of Barcelona that put him ashore in New Orleans on Dec.1, 1847. Sailing from Menorca to the mainland, he’d caught a ship bound for America together with 35 other passengers who were nearly all from Menorca as well. The passenger manifest for the arduous 2 month voyage showed that most were in their hardy teens and 20s, a few in the 30s and 40s, with 15 of the 36 being women and children. Many were single men, but several had their wives and children on board, as well as a few grandparents and cousins. A 29-yr-old single woman, Marguerita Pons, may have been Diego’s cousin, his and Pedro’s mother being a Pons. And another passenger, Marcos Sitges y Mercadal, a 26 yr old carpenter who was my granddaddy’s great uncle, was traveling with 44 yr old Antonio Mercadal, an uncle or possibly an older cousin. Occupations varied. There were several tailors, several merchants, a farmer, a musician, a carpenter (M. Sitges), a smith, a hackler (combs flax fibers for spinning linen), a clerk, and 3 teenagers who listed themselves as students. Was this ocean voyage where the Rosello/Sitges friendship was first forged? Months of day-in/day-out proximity, sharing experiences of death, disease, hardship and tragedy, as well as friendship and love, every minute, 24/7, could easily forge new families and lifelong friendships. I could see that. The Sitges clan was from the port city of Mahon; the Rosellos were from the town of Alayor, 7 miles inland . Did they know each other before sailing to America together? Were there already family ties? . . . . Are the answers lost to the winds? . Menorcans in New Orleans . In November of 1854, a year after Pedro had settled for good in New Orleans, Juan Rosello y Pons, a year younger than Pedro, landed in New Orleans. The 3 Rosello y Pons brothers arrived on a wave of immigration into New Orleans that had already swelled the city to the 3rd largest in the United States and helped make its port one of the most important in the western hemisphere. Immigrants came from all corners where poverty or religious prejudice or political upset was felt… mostly Catholics… from French Canada and Spain’s Canary Islands, from Haiti, from Ireland and Germany, and to a smaller degree, the Balearic Islands. It made sense that Menorcans, who were not happy with the fact that Menorca had recently been transferred to the English throne, were more and more drawn to one of the most prosperous Catholic cities in America. The Menorcan population and culture was not like that of the traditional Spanish, Island Spanish, or even its fellow Balearic Islands. A Meditteranean island off the east coast of Spain, Menorca is only 25 miles from one end to the other but boasts one of the finest deep natural harbors in the Meditteranean, at Mahon. And because of this, it had been previously settled by Moors, Romans and Carthaginians around the time of Christ, and before that by the Bronze Age Minoans around 2500-1500 BC, all the way back to prehistoric peoples who left behind the famous Menorcan megaliths. Its culture was unique and separate from that of mainland Spain, as was their isolated Catalan dialect, and in this strange new America across the ocean, Menorcans sought each other out. . Pedro and the Bienville St. cigar shop . In 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, a New Orleans city directory was published. Pedro Rosello, by then 33 and in New Orleans for 8 years, is listed as a cigar maker with a cigar and snuff store on the corner of Bienville and Exchange Alley, in the SE corner of the Quarter, near the river and its Canal St. boundary. Canal St. was the ‘neutral ground’ that separated the squabbling French and Spanish Creoles in the Quarter from the ambitious American newcomers who came flooding into the city after Louisiana became a State. Refused entry into their insular Creole world, both physically and socially, the ‘barbarian Kaintucks’ were relegated to the relative wilds south of Canal St, which would soon outshine the old Quarter in business and wealth as the elegant Faubourg Ste. Marie. Such internal feuds and infighting probably didn’t concern Rosello, though, and while the old-line Europeans allowed him as a Spaniard to live and work among them in the Quarter, he listed his first name in the directory in the American style, in both spelling and by dropping the maternal surname of Spanish tradition.

Among the 29 cigar stores listed in the business section of the 1861 directory, alphabetically just below Peter Rosello, is John Sabater, whose store is a few blocks south in the American Sector, one block the other side of Canal at 98 Common St.

Among the 29 cigar stores listed in the business section of the 1861 directory, alphabetically just below Peter Rosello, is John Sabater, whose store is a few blocks south in the American Sector, one block the other side of Canal at 98 Common St.

Shortly after that, Pedro Rosello is granted American citizenship.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

U. S. CITIZENSHIP – January 14, 1868 – Louisiana, City of New Orleans

“. . . PEDRO ROSELLO, native of the Kingdom of Spain . . . arrived in the United States in 1852, being then minor, under eighteen years . . . . .” [*error* – no, would have been 24]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Joining Rosello on his corner is Juan Garcia y Mora, a 55 year old Menorcan merchant from the southeast port city of Mahon. He had crossed the ocean 5 years after Rosello with his 3 sons Bernardo, Jose, and Francisco who were 20, 13 & 7 at the time, and established residence on Rosello’s corner, opening a tobacco store a block away on Customhouse and Exchange. By 1866, they have opened a second business, a coffeehouse/saloon next to where they live on Rosello’s corner, which the 21-yr-old Jose is running and paying taxes on as a retail liquor dealer. Juan and his oldest son are still at their tobacco shop down the street, which will eventually be known as Garcia Bros and expand its interests to include tobacco leaf wholesaling, cigar box making and Cuban imports outside the cigar industry. The coffee house disappears from the records, though, and Jose is eventually found working in Rosello’s cigar shop. Whether or not there is any sort of partnership between the Rosello and Garcia y Mora businesses, it is certain that there is a social connection because this is the year that Pedro and Cecilia get married and ask Juan Garcia y Mora to serve as signatory witness.

On the corner of Conti at Exchange Alley, the other side of Rosello, Francisco Sitges, a shoemaker from Mahon, has opened a coffeehouse, moving both his business and residence from around the Old Carondelet Canal turning basin to be closer to the American Sector, much like Henrietta and Carlos Garcia had done. Francisco, 42 in 1866 and only a few years older than Rosello, has been in New Orleans for almost 25 years, and his older brother Marcos Sitges, with a coffeehouse of his own in the heart of the old French Quarter, longer than that. Both Sitges brothers had married a pair of sisters who were also from their home town of Mahon, Catalina and Margarita Taltavull, and both had served during the Civil War in the 5th regiment, European Brigade (Spanish Regt) of the Louisiana Militia. And both families, within a tragic 5 day span during the terrible October of 1866, lost their mothers, and in Francisco and Catalina’s case, both the twins she had given birth to several weeks before. Francisco’s youngest surviving child, Jerome Henry, named for their Taltavull uncle and grandfather still back in Menorca, both named Geronimo, was only 4, and he was only 13 when he lost his father. His big brother Francisco, Jr., only 19 himself, took over the care of the family and his father’s coffeehouse/saloon, and died himself 6 years later. By then, though, 19-yr-old J Henry has left to seek his fortune in Vera Cruz, Mexico.

A year later, a carpenter from Menorca named Bartolome Pico joins the Exchange Alley ‘Menorcan strip’ on Customhouse and Exchange, the corner where Garcia Bros is performing its varied cigar-related duties. A few years younger than Rosello, he had arrived in New Orleans at nearly the same time… in fact, on the same ship as the Taltavull sisters who married the Sitges boys soon after they arrived, and during the Civil War, had served in the 5th regiment, European Brigade (Spanish Regt) of the Louisiana Militia, the same one as Francisco and Marcos Sitges. Again, whether they knew each other is anyone’s guess. After spending some time in Texas, paying both income tax as a retail liquor dealer and sales tax on a billiard table in 1865 and 66, he returned to New Orleans in ’67, which is when he opened a saloon on Exchange Alley.

. Pedro finds Carlos and Henrietta Garcia . Not much is known of Henrietta Cox, except that she was born in Missouri to American parents anywhere between 1805 and 1820, and that her name is also listed as Harriett Coze. In 1866, she could be 46, or 61, or anywhere in between. What little is known of Carlos Garcia is even more confusing. Not only does his age on censuses vary even more wildly than Henrietta’s, putting his birthday anywhere between 1770 to 1810, but there are several Carlos Garcias with no distinguishing markers, except for the one listed as living with Henrietta in 1770, referred to as “Don” Carlos, the elder. This, intimating the existence of a younger Carlos, makes Carlos Jr. the more probable husband of Henrietta. It is known that ‘Don’ Carlos was born in Cuba, that he was a cigar maker, that either he or his son Carlos married Henrietta sometime shortly before 1838, and that they had settled in New Orleans at least by that time. Also, it is likely that ‘Don’ Carlos had other grown children who may have stayed with their sister-in-law/step-mother Henrietta on occasion. In 1850, Henrietta and her 5 children, together with a ‘Carle’ Garcia, were living in the Faubourg Marigny, back of town on Rampart St just outside of the Quarter, downriver from the Old Carondelet Canal turning basin, in a neighborhood that would become a residential hub for Menorcans. He is listed as 65 and Henrietta as 35, but it’s anyone’s guess. Unlike the American/European culture clash and social schism between the old Quarter and the American Sector to the south, the Faubourg Marigny population on the north side of the Quarter was more of a homogenous Creole overflow from the Quarter, the cottages smaller, the streets roomier, and certainly a more peaceable cultural mix of French and Spanish Catholics, together with a strong artisan class of Free People of Color.

(Remember – Because New Orleans is on a brief stretch of the river that shoots up before turning back to its downward path toward the Gulf of Mexico, directions seem bass-ackwards. The north side of the old French Quarter is downriver and the south side is upriver.)

. Location, location… . After the Civil War, however, and the shuffle of power and business dominance associated with it, the Garcias opened up a new center of operations at the far back of the American Sector, on Claiborne where the marshes had only just been drained. Claiborne Ave, unlike the narrow European-style streets in the Quarter and her lower Creole Faubourg Marigny, was a wide oak-lined boulevard at the back of town that paralleled the line of the river for a while, crossing two canals like a big “H” before disappearing into the swamp in the center of the river’s crescent which had always been, and still is as Katrina made painfully clear, the ‘bottom of the bowl’. The old Carondelet Canal, whose turning basin was at the back of the Quarter, ran north, connecting with Lake Pontchartrain by way of Bayou St John. The New Basin Canal, a redundancy barely a mile upriver, was built by the Americans out of exasperation, when the old Creoles’ refusal to let the American ‘barbarians’ use their canal got to be too much. The two canals accessed, via the lake, an outlet to the Gulf of Mexico that was faster and safer than the circuitous, sand-bar riddled river, and because of this, was the preferred route to Cuba from which all things ‘cigar’ came. The Garcias left their extended family clustered along Rampart St in the Faubourg Marigny and moved south and set up a Claiborne Ave residential/business compound directly between the two canals.

. But now the mystery of why the Sabater sisters, at the end of their lives, occupied Pedro Rosello’s tomb in the 1930s had been broadened to include the mystery of why, 70 years before, at the beginning of their lives, they had been taken in by Rosello’s wife’s family. Who were these people? . The Sabater Diaspora . Simple census and birth records make it easy to recreate a schedule of the Sabaters’ life at the very beginning. Juan Sabater, brought from his native Cuba in 1835, had lived in New Orleans since he was 6. He became a cigar maker, was granted his citizenship at 23 in 1852, met a local girl a couple years younger than him, Estelle Pino, from a family who’d emigrated from the Canary Islands several generations before, like his own family had, and married her in 1856. He had a cigar and snuff shop, which the 1860 census lists Pedro as both clerk and owner, and had 5 children over the course of their 8 year marriage; Victoria, Marie, Victor, Estelle, and Albert. Their names alone hint at their adherence to the Victorian era’s preference for all things British over his and his wife’s Spanish ancestry, being several generations removed from it. The city directory pinpoints where this life took place, in the Quarter a block off the river, a buzzing, vibrant location close to the sounds and smells of the docks and the bustling riverfront. But it took the cold dry figures of a tax form to bring alive the poignancy of Estelle’s life. In Dec. ’93, Estelle paid the monthly taxes on her husband’s new business locations, something which, as a woman whose husband was still alive, wasn’t typically done, and she did so 5 months running. Was Juan sick? Itemization of taxed merchandise showed that 1300 cigars were sold in March of ’64, 1500 cigars were sold in April, but only 250 were sold in May. And then, there it was, on June 24, 1864, the death of Juan Sabater, and 14 days later, of little 8-month-old Albert. Little Marie had died some time after she was born, leaving 7-yr-old Victoria, 4-yr-old Victor, and 2-yr-old Estelle. How, in between 1864 and 1870, did she end up living with Carlos and Henrietta Garcia? Why were they not able to stay in their own home? Were they family, and if so, were the Garcia’s related to Estelle’s husband, the Sabaters, or to Estelle and her Pino family. Were the Garcias Canary Island people? As the origins of both Carlos Garcia and Juan Sabater are hazy, they could be of Menorcan, Canary Island, or any other mainland Spanish derivation. Were they just good friends, unrelated countrymen who were taken in when tragedy struck? Is boarder the right word to use for someone whom you leave your tomb to, and all your family documents? In the recent months since I started pouring through Ancestry.com records, I’ve found enough to form something of a picture of the Garcias and the Rosellos, and how they fit into the culture of New Orleans, so why can’t I find anything that points to whether or not they were related? The Sabaters I know, of course. The little child of Juan and Estelle’s that was missing from the 1870 census, the 8 yr old Estelle, would grow up to marry Jerome Henry Sitges, son of Francisco Sitges from the Exchange Alley coffeehouse and nephew of Marcos who crossed the ocean with Rosello’s brother Diego. She and J Henry would have only one child, a son named Percy, my granddaddy, the finest man who ever walked the earth and still the standard by which I compare the integrity of every man I meet.

In 1890, though, Bartolome Pico died and the Sabaters moved back to the Garcia’s Claiborne neighborhood, finding a double with connecting apartments. . Jerome Henry Sitges . In 1891, a young man of 29 who had grown up above Francisco Sitges’ coffee house on Exchange Alley returned home from a long period of work in Panama and listed his new address as 19 Old Levee, the same house where his future wife had been born into the Sabater family 29 years before. Jerome Henry Sitges probably grew up knowing Mr. Rosello and his nice wife, Miss Cecilia, from their cigar store a block down. Perhaps, having no children of her own, she devoted some of her time and affections to those around the neighborhood. He probably knew Mr Garcia y Mora whose home and coffee business were on the same corner as the Rosellos, and his son Jose Garcia y Mora who worked at Rosello’s cigar store. He’d know Garcia y Mora’s business a block further down, next to Bartolome Pico’s saloon, because his cousin Gerald had worked there for a period, and met his future wife there, Mary Ann, who’d been married at the time to Garcia y Mora’s youngest son, Francisco, until his untimely death at only 23. J Henry would not have known that Juan Garcia y Mora had stood witness for Mr Rosello when he married Miss Cecilia, since he’d been only 4, and may not have remembered the occasion at all considering the trauma that came so quickly on its heals, losing both his mom and his aunt, Gerald’s mom, within a 5 day period. He probably also knew Mr. Pico and his coffeehouse on the same corner as Garcia Bros., and his first wife and their kids, but may not have known that Mr Pico had known his mother Catalina and aunt Margarita from their sail across the ocean from Spain, and certainly didn’t know that Pico, 30 years his senior, would one day be his brother-in-law, by their marriage to the two Sabater girls. He may have known the Sabater sisters growing up, if the Garcias had brought the Sabaters with them on their visits to sister Cecilia and her husband Rosello, but not from living in the same neighborhood together. The year that the Sabaters all moved into the Exchange Alley neighborhood was the same year that J Henry turned 18 and left for Mexico to seek his fortune, as was a popular thing for young men in New Orleans to do at the time. Of course, this isn’t to say that there needed to be a linkage by family, occupation or residential proximity for them to know each other. It could simply have been their Menorcan-ness that put them in a social network or benevolent society of some kind, bringing these men together, and their children after them. In 1866, when J Henry and Estelle were still toddlers, his uncle Marcos Sitges was listed as Secretary for Los Amigos del Orden, a Spanish arm of the Masons, which gathered at the Perfect Union Hall on Rampart, two blocks from his home on St. Philip. Yet most immigrants sought inclusion in mutual aid societies; that didn’t mean they took whole widowed families into their homes during life, and their tombs after it. Who were the Sabaters and Garcias to each other?  .

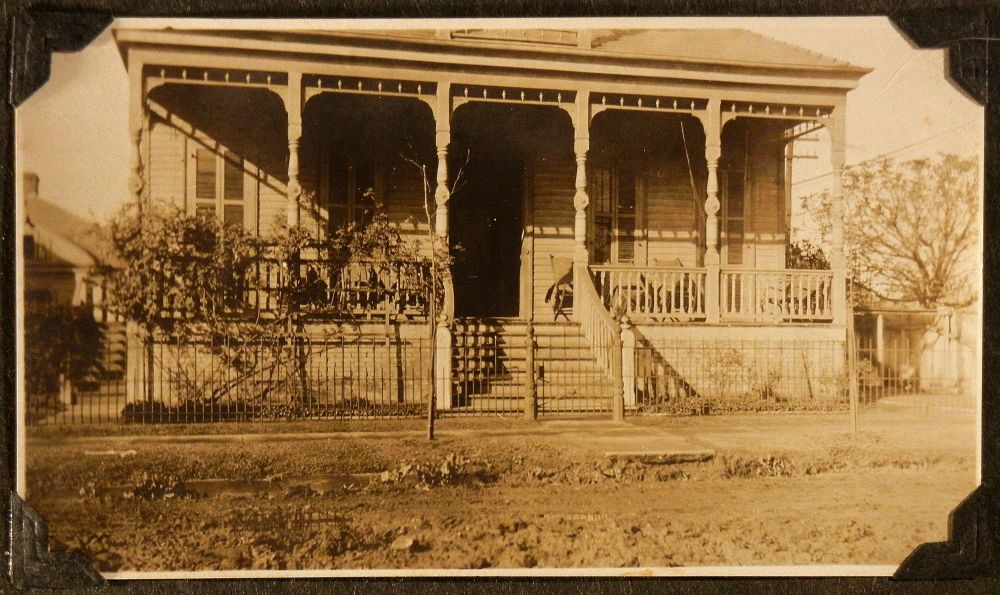

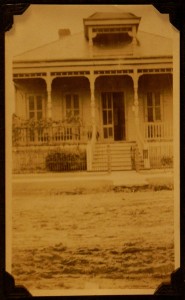

.  . . . . . . . The Sabater’s Rootlessness . It is tempting to imagine that the Sabaters were J. Henry’s landlords at 19 Old Levee St, owning the house they had lived in 30 years before, but the circumstances of the Sabaters living in the homes of others for so long would indicate otherwise. A big change was in the wind when Jerome Henry married Estelle in 1893. Victoria, now widowed, bought a house in the uptown suburb of Lafayette, just the other side of the wealthy Garden District, and left the old city, taking with her not only her 5 little Picos, but the whole Sabater clan as well, including Estelle’s new husband, J Henry, whose meandering business dealings in Mexico and Central America made it practical to have Estelle remain in the safety of her family. It was a neighborhood marked by large roomy lots with homes set back from the street and surrounded by lush gardens and trees. The 1893 directory lists Foucher St as the address of widow Victoria and her son Victor Sabater, 34, who is listed as working for Offner’s store on Canal St in crockery and housewares. And after being the only bread-winner in the Sabater household since Bart Pico’s death, Victor is now joined by J Henry Sitges, his new brother-in-law, listed as a clerk for E. J. Hart, a pharmaceutical wholesaler on Tchoupitoulas St. The 1900 census shows the Foucher St household to be quite a large one indeed. There is the Widow Victoria, now 42, and her 5 children ranging from 13 to 20, the oldest employed as a bookkeeper. There is old Widow Sabater, Mama Estelle, at 65 and her son Victor, who at 40 is a safe bet for remaining a bachelor for the duration. And there is the younger Estelle, with her husband Jerome Henry, a supervisor at a printing company (the one in Mexico?). But now, J Henry and young Estelle have had baby son Percy Henry, now 3, and Cecilia Rosello, 59 and widowed 6 years before, has come to live with them as well. Still with them 10 years later, the 1910 census lists her occupation as a dress maker working out of the house. Wait . . . Is Cecilia Granddaddy’s Aunt Nans?

. . . . . . . The Sabater’s Rootlessness . It is tempting to imagine that the Sabaters were J. Henry’s landlords at 19 Old Levee St, owning the house they had lived in 30 years before, but the circumstances of the Sabaters living in the homes of others for so long would indicate otherwise. A big change was in the wind when Jerome Henry married Estelle in 1893. Victoria, now widowed, bought a house in the uptown suburb of Lafayette, just the other side of the wealthy Garden District, and left the old city, taking with her not only her 5 little Picos, but the whole Sabater clan as well, including Estelle’s new husband, J Henry, whose meandering business dealings in Mexico and Central America made it practical to have Estelle remain in the safety of her family. It was a neighborhood marked by large roomy lots with homes set back from the street and surrounded by lush gardens and trees. The 1893 directory lists Foucher St as the address of widow Victoria and her son Victor Sabater, 34, who is listed as working for Offner’s store on Canal St in crockery and housewares. And after being the only bread-winner in the Sabater household since Bart Pico’s death, Victor is now joined by J Henry Sitges, his new brother-in-law, listed as a clerk for E. J. Hart, a pharmaceutical wholesaler on Tchoupitoulas St. The 1900 census shows the Foucher St household to be quite a large one indeed. There is the Widow Victoria, now 42, and her 5 children ranging from 13 to 20, the oldest employed as a bookkeeper. There is old Widow Sabater, Mama Estelle, at 65 and her son Victor, who at 40 is a safe bet for remaining a bachelor for the duration. And there is the younger Estelle, with her husband Jerome Henry, a supervisor at a printing company (the one in Mexico?). But now, J Henry and young Estelle have had baby son Percy Henry, now 3, and Cecilia Rosello, 59 and widowed 6 years before, has come to live with them as well. Still with them 10 years later, the 1910 census lists her occupation as a dress maker working out of the house. Wait . . . Is Cecilia Granddaddy’s Aunt Nans?

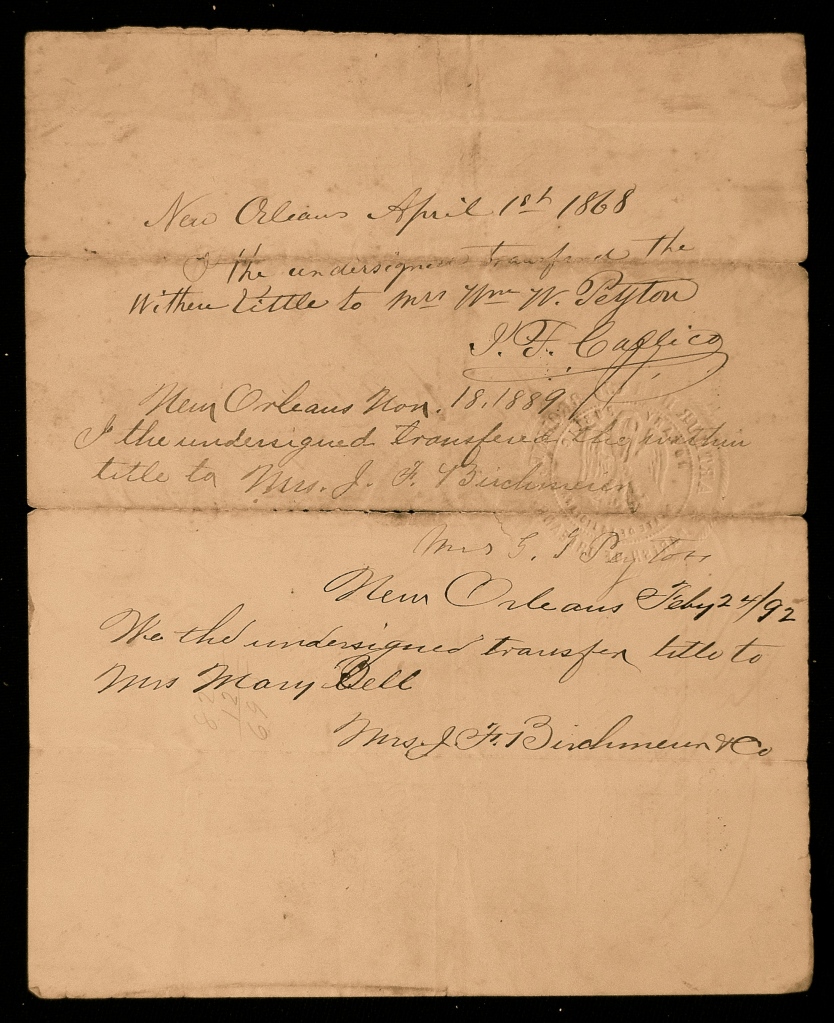

The bill for Rosello’s funeral service and the title to his tomb were among Granddaddy’s papers. The original name on the title is unfamiliar, and dated April 1st, 1868, 26 years before Rosello would need it, and according to handwritten annotations on the back, changes hands 4 times between 1868 and ’92.

. . . . . . I can only assume that, having run out of space on the back of the original title, the transaction two years later, between the last noted owner and the Rosellos was written on something that has since been lost, because the plot number identifies it as definitely the one Rosello and the Sabater girls are in..

. . . . . . I can only assume that, having run out of space on the back of the original title, the transaction two years later, between the last noted owner and the Rosellos was written on something that has since been lost, because the plot number identifies it as definitely the one Rosello and the Sabater girls are in..  . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Nov.13, 1894” . . . “MRS. ROSELLO . . funeral of Mr. PEDRO ROSELLO y PONS” “1 Satin lined Rosewood Burial Casket – Finest Hearse and Attendance, $85 . ” “7 Carriages, $28 . . .” . “Sexton’s fee St. Louis Cemetery . . . ” [ERROR, Lafayette, not St. Louis] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Something else that’s interesting . . . actually, maddening . . . about the 1900 census? Cecilia lists her relation to Victoria as her aunt, which she can’t be. She could be something like an aunt if she and Victoria’s father had been cousins. Old Man Carlos’ marriages and children in Cuba are too far back to know, so we can only guess. If he had a daughter who married a Sabater during their days in Cuba, and a son Carlos Jr who married Henrietta, then her son Juan and Carlos Jr’s daughter Cecilia would be first cousins, and Cecilia would be 1st cousin-once-removed, which is often like an aunt, to Juan’s children Victoria, Victor and Estelle. The 1910 census is much the same, with Cecilia, at 68, again listing herself as aunt to Widow Victoria, still listed as the head of household, together with Victoria’s mother Estelle, now 75, though J Henry’s presence in both 1900 and 1910’s censuses belies the fact that he has spent much of the decade in between gone.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Nov.13, 1894” . . . “MRS. ROSELLO . . funeral of Mr. PEDRO ROSELLO y PONS” “1 Satin lined Rosewood Burial Casket – Finest Hearse and Attendance, $85 . ” “7 Carriages, $28 . . .” . “Sexton’s fee St. Louis Cemetery . . . ” [ERROR, Lafayette, not St. Louis] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Something else that’s interesting . . . actually, maddening . . . about the 1900 census? Cecilia lists her relation to Victoria as her aunt, which she can’t be. She could be something like an aunt if she and Victoria’s father had been cousins. Old Man Carlos’ marriages and children in Cuba are too far back to know, so we can only guess. If he had a daughter who married a Sabater during their days in Cuba, and a son Carlos Jr who married Henrietta, then her son Juan and Carlos Jr’s daughter Cecilia would be first cousins, and Cecilia would be 1st cousin-once-removed, which is often like an aunt, to Juan’s children Victoria, Victor and Estelle. The 1910 census is much the same, with Cecilia, at 68, again listing herself as aunt to Widow Victoria, still listed as the head of household, together with Victoria’s mother Estelle, now 75, though J Henry’s presence in both 1900 and 1910’s censuses belies the fact that he has spent much of the decade in between gone.  . Something happens in 1914, however, that causes Estelle, J Henry and 18 year old Percy to leave their Foucher St home of 21 years and rent another house, taking Cecilia with them, while the elderly Estelle stays behind with her daughter Victoria. J Henry had been home for good since 1909, which may have been a slow catalyst for him wanting to leave Foucher St and have a place that he could at least feel master of, even if he could not afford to actually own it. In 1916, Percy graduates college and gets a job clerking at a bank, and within months, the Sitges clan and ‘Aunt’ Cecilia move again, to a small rental house on Camp St. farther uptown. In 1918, Percy enlists in the army, and in a letter home to his mother, sent from his training camp in Auburn, Alabama, he closes with ‘Love to Nans, Papa and all the folks at home’ – further confirmation that Cecilia Garcia Rosello is Granddaddy’s ‘Aunt’ Nans. Worthy of note is his reference to Foucher St as home, which indeed it was for the first 18 years of his life. The following summer of 1919, some months before Percy turns 23, his Nans dies at 80. Six years later in 1925, Percy now 29 and an asst trust officer at his bank, his grandmother, matriarch of the Sabaters dies at 91. Shortly after, around 1926 or 27, Percy meets a little Cajun minx of a girl studying music at the Conservatory of Music, and both his parents will have the chance to get to know the woman whom their son will marry, though his father, who dies in August of 1929, will not live to see his wedding. Percy and his mother now alone, they soon leave their Camp St house of 13 years, and by the summer census of 1930, they are in a smaller apartment on Jeannette St among the dairy farmlands of the Carrollton area at the end of the streetcar line. In the Spring of 1931, he brings his new bride to live with them. I always knew that Tisolay and Mama Sitges had lived together for the last couple years of Mama Sitges’ life, and that they’d grown very close, but I’d never done the math. Mama Sitges died in July of ’33 and my mother was born only 3 months later, in October of ’33. Mama Sitges lived through the first 6 months of Tisolay’s pregnancy with her only grandchild, but died before being able to see her. Ah, how she must have yearned to hang on just those few months more. Tisolay has a group of photos taken of the inside of the Jeannette St apartment, several of which have her standing behind the piano. She used to laugh, saying she was hiding behind the piano because she was pregnant and embarrassed about it. She used to point out the many things in the photos that belonged to Mama Sitges… the grandfather clock, the oriental rug, paintings on the wall, this vase, that bust of St. Cecilia, the patron saint of musicians. It never occurred to me, though, that everything in that apartment would have been Estelle’s, the things granddaddy grew up with. It wouldn’t have made sense for the newlyweds to buy anything for the house in the economic midst of the Depression when bringing Estelle to live with them meant bringing an entirely furnished home with her. So, when Mama Sitges died and Granddaddy became the owner of his parents’ possessions, it also makes sense that Cecilia’s things would have been among them . . . including Pedro’s papers!! So THAT’s how we came to have so many of Pedro Rosello’s documents, and his tomb. But without being related, would we have really used it? Wouldn’t we have sold it? But then, if someone else would buy it and use it, why wouldn’t we? After all this searching, am I still gonna be left hanging about the mystery of Rosello’s tomb? . . and leave y’all hanging as well? In fairness, though, and in closing, it’s not like we didn’t solve anything. Regarding Aunt Nans – If Granddaddy “was raised by an Aunt Nans”, a third woman besides Estelle and Victoria, I feel safe in assuming that Aunt Nans was Cecilia, the ‘aunt’ to Victoria in the 1900 census and the ‘Nans’ from Granddaddy’s 1909 First Communion card. And Henrietta Coze was Cecilia’s mother, mother-in-law to the Pedro Rosello from the family tomb. Plus there’s one more small discovery I can give you, about the photograph of the 60ish woman that Tisolay and I had always thought was Henrietta.

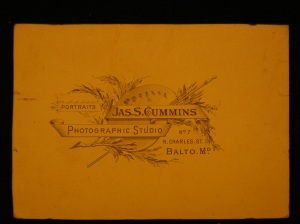

. Something happens in 1914, however, that causes Estelle, J Henry and 18 year old Percy to leave their Foucher St home of 21 years and rent another house, taking Cecilia with them, while the elderly Estelle stays behind with her daughter Victoria. J Henry had been home for good since 1909, which may have been a slow catalyst for him wanting to leave Foucher St and have a place that he could at least feel master of, even if he could not afford to actually own it. In 1916, Percy graduates college and gets a job clerking at a bank, and within months, the Sitges clan and ‘Aunt’ Cecilia move again, to a small rental house on Camp St. farther uptown. In 1918, Percy enlists in the army, and in a letter home to his mother, sent from his training camp in Auburn, Alabama, he closes with ‘Love to Nans, Papa and all the folks at home’ – further confirmation that Cecilia Garcia Rosello is Granddaddy’s ‘Aunt’ Nans. Worthy of note is his reference to Foucher St as home, which indeed it was for the first 18 years of his life. The following summer of 1919, some months before Percy turns 23, his Nans dies at 80. Six years later in 1925, Percy now 29 and an asst trust officer at his bank, his grandmother, matriarch of the Sabaters dies at 91. Shortly after, around 1926 or 27, Percy meets a little Cajun minx of a girl studying music at the Conservatory of Music, and both his parents will have the chance to get to know the woman whom their son will marry, though his father, who dies in August of 1929, will not live to see his wedding. Percy and his mother now alone, they soon leave their Camp St house of 13 years, and by the summer census of 1930, they are in a smaller apartment on Jeannette St among the dairy farmlands of the Carrollton area at the end of the streetcar line. In the Spring of 1931, he brings his new bride to live with them. I always knew that Tisolay and Mama Sitges had lived together for the last couple years of Mama Sitges’ life, and that they’d grown very close, but I’d never done the math. Mama Sitges died in July of ’33 and my mother was born only 3 months later, in October of ’33. Mama Sitges lived through the first 6 months of Tisolay’s pregnancy with her only grandchild, but died before being able to see her. Ah, how she must have yearned to hang on just those few months more. Tisolay has a group of photos taken of the inside of the Jeannette St apartment, several of which have her standing behind the piano. She used to laugh, saying she was hiding behind the piano because she was pregnant and embarrassed about it. She used to point out the many things in the photos that belonged to Mama Sitges… the grandfather clock, the oriental rug, paintings on the wall, this vase, that bust of St. Cecilia, the patron saint of musicians. It never occurred to me, though, that everything in that apartment would have been Estelle’s, the things granddaddy grew up with. It wouldn’t have made sense for the newlyweds to buy anything for the house in the economic midst of the Depression when bringing Estelle to live with them meant bringing an entirely furnished home with her. So, when Mama Sitges died and Granddaddy became the owner of his parents’ possessions, it also makes sense that Cecilia’s things would have been among them . . . including Pedro’s papers!! So THAT’s how we came to have so many of Pedro Rosello’s documents, and his tomb. But without being related, would we have really used it? Wouldn’t we have sold it? But then, if someone else would buy it and use it, why wouldn’t we? After all this searching, am I still gonna be left hanging about the mystery of Rosello’s tomb? . . and leave y’all hanging as well? In fairness, though, and in closing, it’s not like we didn’t solve anything. Regarding Aunt Nans – If Granddaddy “was raised by an Aunt Nans”, a third woman besides Estelle and Victoria, I feel safe in assuming that Aunt Nans was Cecilia, the ‘aunt’ to Victoria in the 1900 census and the ‘Nans’ from Granddaddy’s 1909 First Communion card. And Henrietta Coze was Cecilia’s mother, mother-in-law to the Pedro Rosello from the family tomb. Plus there’s one more small discovery I can give you, about the photograph of the 60ish woman that Tisolay and I had always thought was Henrietta.  I was curious about the photographer’s stamp on the back, the Baltimore photographer James S. Cummins. No one in the family that I knew of was from Baltimore; why have a portrait done there?

I was curious about the photographer’s stamp on the back, the Baltimore photographer James S. Cummins. No one in the family that I knew of was from Baltimore; why have a portrait done there?  . I never found a clue regarding that, but I googled the photographer’s name and the address of his studio, and found out that he only had his studio there for two years, 1887 and 1888. Henrietta died in 1874! But guess who was around 50 in 1888 . . . Cecilia! Cecilia, who was ‘Aunt Nans’, and who lived with my Granddaddy for the first 23 years of his life. How much more it means to me, how much more of a link to the childhood of my beloved Granddaddy it represents. I’m sorry Henrietta. You certainly aren’t forgotten, not after the months I’ve been living in these old records, and all the people out there that I’ve now given you to. But Cecilia, now we know it’s you. Perhaps one day the riddle of whether the Garcias and Rosellos are related to the Sabaters will be solved, but for now, I am satisfied by what pieces of the puzzle I have managed to put together. . . . . Thanks so much, all of you who have joined me in my search for Henrietta, Rosello’s Tomb and Aunt Nans. ______________ © postkatrinastella – All rights reserved.

. I never found a clue regarding that, but I googled the photographer’s name and the address of his studio, and found out that he only had his studio there for two years, 1887 and 1888. Henrietta died in 1874! But guess who was around 50 in 1888 . . . Cecilia! Cecilia, who was ‘Aunt Nans’, and who lived with my Granddaddy for the first 23 years of his life. How much more it means to me, how much more of a link to the childhood of my beloved Granddaddy it represents. I’m sorry Henrietta. You certainly aren’t forgotten, not after the months I’ve been living in these old records, and all the people out there that I’ve now given you to. But Cecilia, now we know it’s you. Perhaps one day the riddle of whether the Garcias and Rosellos are related to the Sabaters will be solved, but for now, I am satisfied by what pieces of the puzzle I have managed to put together. . . . . Thanks so much, all of you who have joined me in my search for Henrietta, Rosello’s Tomb and Aunt Nans. ______________ © postkatrinastella – All rights reserved.