(cont’d from pg.3 of 5)

The McDonald pitless farm scale:

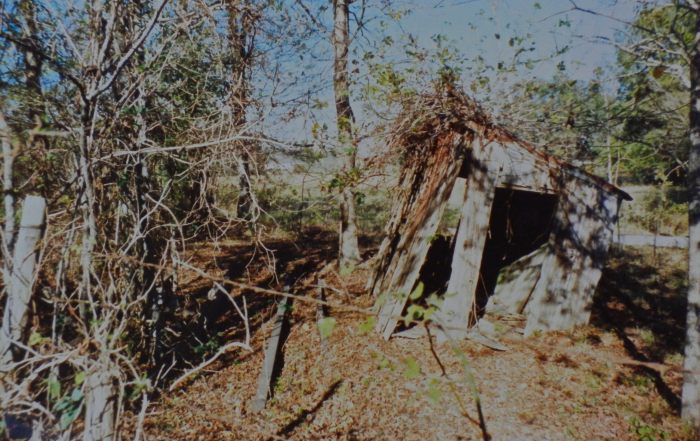

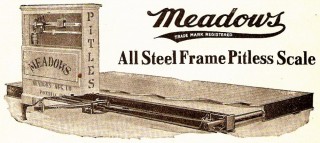

The most interesting thing I found on that front square, though, I didn’t find until the following winter’s thinned foliage allowed me to penetrate a thick patch of woods and berry brambles. Or I should say, that’s when I found what it was in. It was back up by the road, straight up the southern fence line from the water. My initial hesitancy to get mired in the thorns was reinforced a few feet in by a makeshift barbed wire fence, its purpose long since lost to time, which I also had not seen until the trees had shed their leaves. But coming around and approaching it from the road gave better access and a clearer view inside, where there was a small crooked cypress hut with a slanted tin roof, leaning nearly to the point of toppling over on its back. And in front of it were railroad tracks, several sets, that didn’t make sense given where the old railroad up by the sugarcane had been. On closer inspection, I saw the tracks were only segments about 12′ or so long, immovably rooted to the earth though I couldn’t find anything like cross ties that they were attached to. And they didn’t connect to the road or anything else, either, but they were positioned off from the road at an accessible 45º angle, though, and the stretch of roadside ditch that lay in their path was bridged by an overgrown, long-forgotten driveway set atop a flow pipe. So it had definitely been meant to be accessed straight from the road, at least before modern barbed-wire and nature threw up their blockades. I couldn’t picture what kind of truck or wagon with wheels meant to sit on railroad track could also maneuver through mud and a flat paved road, or why there was more than one set of tracks side by side, but there they were.

Scattered around behind the hut were fallen pieces of heavy iron fittings so massive that they would have needed a crane truck to be removed, pieces that seemed to me to be from some sort of derrick for loading and unloading what I assumed was sugarcane; a 25 foot concrete-filled beam stretched out across the ground, a kind of base upturned on its side that was as big around as I was tall, and a set of giant iron gears slowly sinking into the ground beneath it.

It wasn’t until a couple years later, while I was delighting in a super-rare snow and stomping around in it like a kid, that I noticed through the leafless thicket that a crude window shutter from the hut had fallen off its hinge onto the ground, went in to get it, then saw something peaking up through the leaf litter inside the hut.

.

.

.

.

.

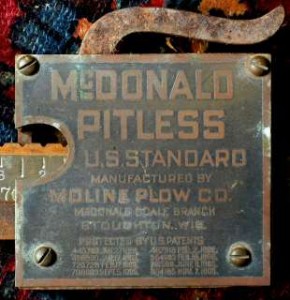

What I pulled out, piece by heavy iron piece, were hooks, a lever of some kind, a corroded old battery, an old strap hinge, and a bunch of hanging free weights. The main thing, though, I almost couldn’t pick up, a scale arm attached to a wooden mooring with a name plate on it… McDonald Pitless, from McDonald Scale Branch, Moline Plow Co., with a patent date, Nov.7, 1905. (*sigh* . . Tisolay was 10 months old.) The cousins had told me that Adeo had had a sugarcane weigh station, though what that was I’d had no idea, and that the neighboring farmers would pay to use it before carting the cane off to the processing plant up by Breaux Bridge. I had no way to visualize it, though, and curiosity lit up my brain.

.

.

.

.

.

.

I brought everything back home to New Orleans, hose-blasted and scrubbed them clean, wrapped it all up in an old sheet and duct tape, and promptly forgot it.

.

It was twenty five years, several moves and a few hurricanes later (including K…, she of the unmentionable name) before I finally unpacked everything to photograph for this post, but during that time, everything had changed. The internet existed. A single google click for “MacDonald Pitless scale” was all it took. Knowing that it was a sugar cane weigh station hadn’t given me any way to visualize how the thing worked, or more to the point, imagine my Tisolay’s granddaddy Yépope, her name for Adeo, standing there using it; it was all just iron bits from a crumbled whozits buried in a foot of leaf litter, along with some curious train track sections. But there on google was a diagram of what it looked like put together, including a cutaway of how it was connected to the scale platform in front of it which, yes, was built on a framework of train track segments. . . Hot damn! And then I went to Ebay where someone had posted a photo… and there it was, cabinet and all. That’s what Adeo had built the hut for, to keep it out of the weather.

.

I feel silly trying to describe to people why these sudden, unexpected google discoveries bring a lump to my throat, but there it is.

.

I didn’t think about it much at the time, but reading about these portable pitless scales made me think of this thing as a harbinger of modernization and change on a grander scale (no pun intended), a sign that the 20th century was ushering in an age of machines and steam power, and railroad penetration into the previously isolated world of the reclusive Cajuns, an isolation that had held their families and ethnicity together since the 1600s.

_______________________

The 1900 census of St. Martin Parish: two houses

The turn of the century brought personal family changes to the Hebert farm as well, and did so barely 14 months into the new century.

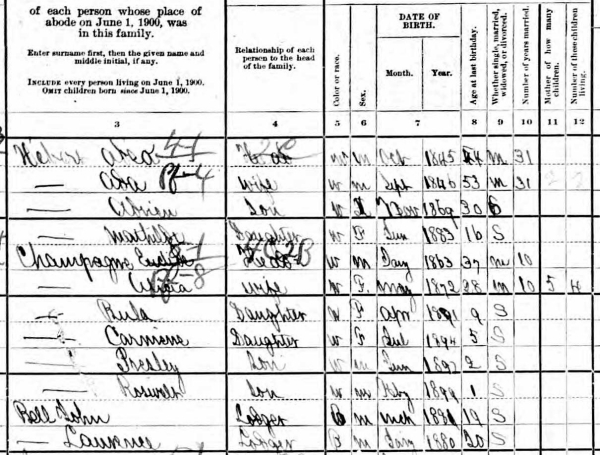

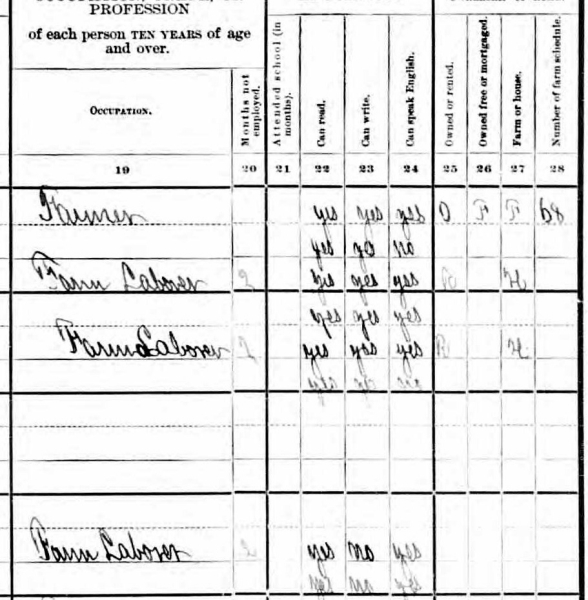

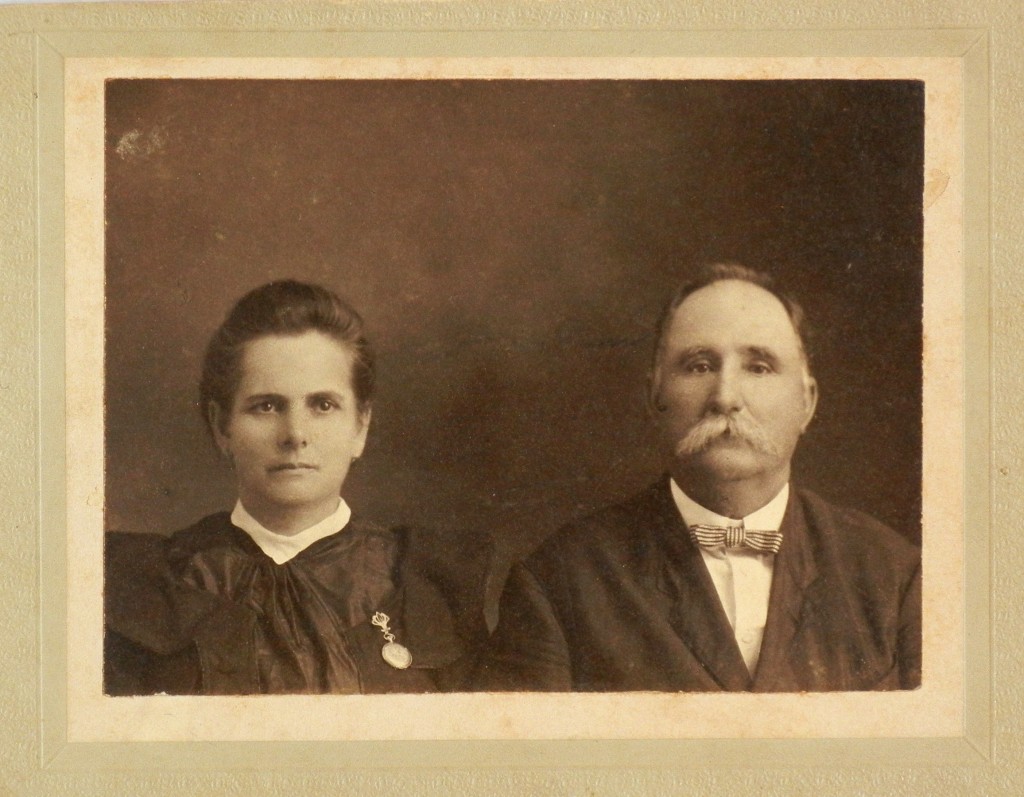

The 1900 St. Martin Parish census, as it turns out, is the last time we see the family together. Adeo and Ada, now in their 50s, are in the house up by the road next to the pecan tree, living with Adrien, who has never married and at 30 has no doubt taken on much of the farm’s management, and Mathilde, who at 17 must surely have romance on her mind. Their older daughter Alicia, now 28 and 10 years married, runs a second household under the big oak where the south fence slopes down into the Bayou Teche, a house I have speculated endlessly about (read more on pg. 3) but, in the end, will probably never know anything about. She and her husband J. Euclide Champagne, now 37, have 2 daughters Beulah and Carmen, 9 & 5, and 2 sons Presley and Roosevelt, 2 & 1, as well as two lodgers, brothers John and Lawrence Bell, 19 & 20. Adeo is listed as 1) a sugar cane farmer, 2) who owns his home and farm free and clear, and 3) employs his son & son-in-law Adrien and J.Euclide as farmhands, as well as John and Lawrence Bell, two African-American hired hands whose family lives nearby.

The census has gotten more detailed over the years with the information it records, and it now tells us that all the Hebert adults can read and write in their principal language, French. Only the men speak English, however, presumably for business reasons. [Aside, relevance to be clear soon: Elsewhere in the 1900 census, about 7 miles downstream from the Hebert farm almost to St Martinville, a 35 year old spinster schoolteacher named Sidonie Resweber, the only one of her siblings to never marry or leave home, is taking care of her elderly widowed father, Antoine, a Frenchman from the Alsace region who only has a few more months to live.]

Deaths, weddings, modernizations, migrations and the railroad: changes to 20th century Cajun ways

Fourteen months into the new century, though, on February 16 of 1901, Adeo’s wife Ada Babin Hebert, the youngest of 22 children, died at the age of 55, and nothing was ever the same after that. Three miles south of the farm just below LaPointe, the owner of an old land grant had been dividing part of his land into lots for a settlement that was forming on the Teche that would later be known as Parks, and something about this new community caught the eye of J Euclide. Adeo’s younger brother Henry Hebert, and three of his sons, were taking the lead in the building of the town, and perhaps it was a job with them that caught his attention, or the desire to escape the Teche’s propensity to flood their waterfront house. Or perhaps the death of Tiwazzo’s mother simply freed them to do what they’d been wanting to do for a while. In any case, a few years after Ada’s death, J.Euclide moved his family from Adeo’s farm to the newly divided settlement south of LaPointe.

Around the same time, 22-yr-old Mathilde married Michel Bourdier, a Breaux Bridge boy who got a job with the Louisiana Western Railroad Co. in Lake Charles. Lake Charles, only 80 miles to the west, was a buzzing port town of ex-pat Texans that must have seemed a world away from Mathilde’s Cajun people, the Bayou Teche, and the sugarcane fields, but leave she did, and Adeo & Adrien were then by themselves. How the guys felt about this, being abandoned bing-bang-boom by the civilizing influences and household ministrations of the 3 Hebert women in as many years, is anyone’s guess. But no sooner did Mathilde’s departure free them to live a bachelor’s life than Adeo got married again.

On February 27 of 1905, he married the spinster school teacher down by St. Martinville who had taken care of her father in his last years, Sidonie Resweber, now 40, who would become known affectionately as Tante Sin. Odds are, there was a family gathering for the occasion, maybe a fais-do-do with a steaming kettle of good cooking on the wood stove, and music and dancing indoors out of the February cold. And odds are Alicia, J. Euclide and the family drove their buggy up to join them. If so, the bride would probably have had to share the limelight, and would have warmly done so, with a tiny impromptu guest of honor, the new 10-week-old baby girl Alicia had just given birth to, Adeo’s newest grandchild, little Marie-Stella Champagne, my funny Tisolay.

.

The House in Parks:

In the late 1980s when I first started visiting Teche country and looking up the sites of my grandmother’s childhood memories, she couldn’t give me much direction with the Parks house or how to find it. She could only have been around 3 when her father moved the family away again, joining Mathilde and Michel in Lake Charles, and she had little memory of it; just that it had been a 2-story wood frame house with a deep gallery on the first floor, and that it had at one time been the church rectory. I found the Catholic church with no trouble, but next to it … and I dreaded telling her this; put it off for months …, there was only a 1970s brick ranch house for the church’s rectory. But when I did finally tell her, she remembered something. The house had been sold by the church, auctioned off for $1, a single dollar, to anyone who would move it off the church’s property. She said that somebody had come and floated it across the bayou to the other side!!!

When I returned to look for it, on the other side of the Teche, there were no 2-story houses that could have dated to 1905. There was one that looked a bit old, though, so one day I rang the doorbell and introduced myself to an older man who couldn’t have been nicer, a middle-aged black gentleman whose father had bought it from the church and indeed, yes, floated it across the Teche. He showed me in and offered me coffee, and I told him that my grandmother’s strongest memory of the house was her father bringing a cup of coffee-milk upstairs to her every morning. I saw where, halfway up the staircase, the 1st floor ceiling cut away, and told him how often she had described how her daddy would tell her to duck, because every morning, she started her day with her father bringing her downstairs on his shoulders. He told me that his father had raised his family to value hard work and education, and that he himself had seen several of his children graduate from USL in Lafayette, one of them now running the family business. He was so proud.

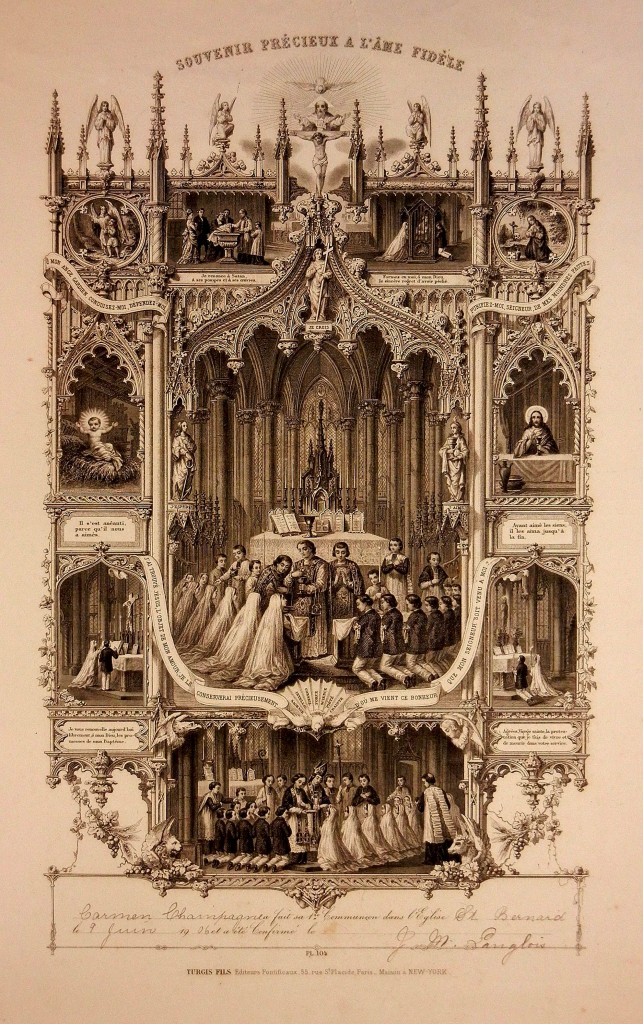

But there was something that never quite sat right with me about the Craftsman architectural style penetrating the backwoods enclave of Cajun country as early as 1900, when it had barely crossed the ocean from England yet. And sure enough, a few weeks ago, I heard back from the Parks church with information that the house that my pleasant coffee companion’s father floated down the bayou in the 70’s had been built by the church in 1938, probably on the site of where her house had been. Tisolay’s memories of a big 2-story house, her morning coffee, and her ride down the stairs on her father’s shoulders, had to have been of the Lake Charles house, which she spent her entire childhood from the age of 3. It seems that only a few years into the construction of the little town of Parks on the Teche, a hurricane brought a flood that destroyed the church they were only half-way through building, and nowhere near through paying for. The debt halted the town’s growth in its tracks, playing a role, I would imagine, in J. Euclide’s decision to pull up stakes again for the thriving port town of Lake Charles where his wife’s sister’s family had settled. The last record I have of them on the Bayou Teche is Tisolay’s sister Marie-Carmen making her First Communion in 1906, at St Bernard’s church in Breaux Bridge, and when their brother Presley died in 1963, the itemized list of his personal possessions included a gold ring with the letters Lake Charles High School, 1908.

The railroad out of Texas was making inroads into Cajun country and on through to New Orleans, and perhaps J. Euclide’s new brother-in-law Michel served as a foot in the door, because by 1910, the Calcasieu Parish census listed J. Euclide as working at the Southern Pacific freight depot in Lake Charles. That was the year that Tisolay remembered traveling back to Breaux Bridge to visit her grandfather, playing on the pecan tree and running back to meet the train as it passed to deliver the newspaper. This was the last memory of her grandfather and the family farm in Breaux Bridge I ever heard her speak of.

Adeo died on September 24, 1917, at the age of 72, 12 years after his marriage to Tante Sin. He left the farm to Adrien, by then 47, entrusting Tante Sin to his care for the rest of her days, and his Dec.12, 1917 succession described the rest of his estate as including a small tract of virgin cypress woodland around Lake Martin, the “cane, corn, hay and pecan crops . . . 1 horse, 1 cow, one wagon, one cultivator, two plows, kitchen utensils, a few household effects and . . . ½ of a corn planter, ½ of a hay rake, and a share in the derrick . . .”

Tante Sin was only 5 years older than Adrien, though, and the rest of her days with Adrien constituted 2 ½ decades and a whole ‘nuther family. By 1930, they had taken in Adrien’s cousin, the 19-yr-old granddaughter of Adeo’s baby sister Felonise, and by 1940 this girl, still living with them, had married and brought a new baby girl into the household, the first in 40 years I showed you photos of this young family and Tante Sin back on pg. 2.

But soon after this, Adrien brought in his last crop of sugarcane in the winter of 1941 and died on August 22 of 1942 at the age of 72, leaving his two sisters in Lake Charles $1184.49 in a bank account (about 18k in today’s money), 21 shares of stock valued at $950 dollars(14k in today’s dollars) in the new Breaux Bridge Sugar Cooperative, established only 4 years before, and 8 shares of stock in the Opelousas Production Credit Association at $40. Also included were 4 mules, 3 cows, 1 calf and all farm implements. I wonder if those old cypress cane wagons from pg.1 had been among those implements.

With Adrien’s death, there was no one left of the family on my great-grandfather’s farm. On May 22 of 1948, at age 83, Sidonie Resweber Hebert died, and two years later, the husband of her little adopted family died. In the mid-1960s, the wife and daughter, who never married, left the aging and by-then-unliveable house and moved to Breaux Bridge where they built a new brick ranch house on the family lands the wife had grown up on. They took the last known photo of the place in 1964, and in the mid-1980s, the abandoned house was finally taken down.

As I described in pg.2, when I first arrived to the area in the 1980s, there wasn’t a single building left on our land… only the leaning shed that had sheltered the weigh station. But in 1987 I was young, newly married, and hopelessly enamored with the moss-draped bayou of my Tisolay’s heritage, so I thought that surely the day would come when I would be teaching my own children about their magical great grandmother’s heritage, and we would do something I have always wanted to do… fell one of those giant cypresses from the sunken forest at the back of the property, drag it back up to the bayou underneath the oak, take an ax and adze, and hollow out a pirogue(canoe) from a single tree trunk like the old cajuns did. But those children never came to be. So . . . as the only child of an only child, our family’s presence on my grandmother’s land will die with me.

(* For a sweet little 10-minute film of a pirogue being made in 1948, that would never have been made if a filmmaker hadn’t looked for a Louisiana pirogue for a movie and found out what a dying art pirogue-making was, click here. I will never make one, but perhaps now you will*;-)

. _________________ .

Racial changes in post-Civil War Cajun country

The next chapter in my grandmother’s life takes us to Lake Charles, but that will have to a wait a bit. Because while my grandmother’s life in Breaux Bridge ended when she moved to Lake Charles, I recently found out that the story of my involvement with the Breaux Bridge land does not end with my grandmother. After I wrapped up the story and posted it, I shifted gears from writing mode to camera mode to arrange a photo still-life to go with the story, but within days, I received a comment on one of the pages from someone in Texas who said she was researching a distant cousin from Breaux Bridge and had a document in which the gr-gr-grandfather I had been writing about, Adeo Hebert, was mentioned, and that she could send me the link to it if I were interested.

And it turns out that the last section of the chapter on 20th century changes in traditional Cajun ways, which took note of evidence in the 1900 census that pointed to social and racial gains being made in post-Civil War Louisiana, now merited an entire story of its own. To continue with this truly fabulous story, which I am so lucky to have had fall into my lap, come with me to the story of Thélèsphore.

or

Go on to pg. 5, Breaux Bridge: the sculpture or Return to pg.1 of 5

and as usual,

Thanks so much for your interest in my funny Tisolay’s story.

© All rights reserved – postkatrinastella.com

.

.

.

.