.

…. (cont’d from pg.2 of 5)

Unlike the roadside square with the pecan tree, which had impenetrable 6 ft grasses covering everything from view, the square fronting on the bayou was a more open, visible pasture, partly because the family had given various neighbors permission to graze their horses and cattle on the land. And where the back square had nothing left of the structures that had once been there, there were little signs of ancestral life on the Bayou Teche side of the highway. They weren’t immediately seen, at first, but they were there, remnants of the life that had once been.

There was the old gate up by the road that had separate walk-thru and drive-thru entrances, and a kind of bracket overhead, perhaps for hanging a sign. Tisolay remembers it being a dirt path for horse & carriage.

Beyond it, there were patches of saplings and young trees in the middle of the pasture that still retained something of the square-shaped outline of the barns and sheds they had once encircled, like ghosts. The one farthest back sat on a bluff above a semi-circular dip down to the water that looked like it would have filled up during high water like an inland lagoon.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In the trees was an axle of a long-rusted-away wagon forever locked inside the trunk of a tree that had grown up and around it. Did this indicate how that shed would have been used?.. a garage, a repair shed? Had a roof once covered it right where it lay? By the hardest, I managed to remove one of its wheel hubs after something inspired me to take it home.

Twenty years later, during a year-long flurry of refinishing things damaged in Katrina’s flood waters, I banged off a bunch of encrusted junk and corroded iron from the thing, wire-brushed, derusted and seal-coated it, then hung it up as a pot rack in my husband’s kitchen, my new post-Katrina world.

Totally works, don’t you think?!

_____________________________

.

The corner under the oak:

Following the water to the south property line, where the fence gradually slopes down into the Bayou Teche, is an ancient oak tree that shades this idyllic corner all day until the late afternoon sun comes in sideways from underneath. Its knotted roots extended out a good 10 ft from the trunk all the way around, and I spent many an hour tip-toeing from knot to knot, in circles around the trunk, like they were stones in a brook.

Tisolay remembered climbing around those roots and how gnarly they were even then, and was surprised the tree was still alive… but I told her what people thought at the time, that the Live Oak had a life span of 600 years; 200 growing, 200 in adult dormancy, and 200 deteriorating, which meant that it was a safe bet that her tree had been there when the native Attakapas were the only people in the area, maybe even before Europeans found the western hemisphere. I read somewhere recently, though, that now they think it’s more like 800 years.

Beside the tree, enmeshed by barbed wire from a more modern era, were remnants of an old cypress fence with boards that were split, eroded, and covered in lichens and mosses of every color, but somehow still stood, managing to escape being trampled to splinters by ‘the locals’, the neighbors’ animals we let graze on the property. I would always tell the cousins what it meant to put my hand on these things that my ancestors’ hands had also touched, and they’d politely listen, with no fascination for the family history that was nothing more than daily life to them, while I went on about old fence boards that represented for them nothing more than trash they hadn’t gotten around to getting rid of.

I asked them if they’d mind my taking a few of the fence boards that had already fallen on the ground home with me, and they just looked at me quizzically. “Mais, it’s yours.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

About 40′ in from the tree where the high ground started to level off, a few feet from the fence, were four concrete piers toppled over in the weeds; foundation cones placed beneath the sills to raise a house up off the ground and above the Spring floodwaters.

I later found out from the cousins that there had been a house here that they remembered Adrien renting to his farm workers; a fence, too, coming out from the side of the house, then turning toward the water at about where the middle tree of the three oaks was.

.

.

.

.

.

They also showed me where there had been two barns, a large one up front by the gate and the smaller one in back, where I’d found the wagon axle, and a sugar cane weigh station up by the road where a dense thicket of scrub trees now stood.

.

I don’t remember when it was that the light dawned on me that the house my cousins remembered from the 30’s & 40’s as the farm workers’ house down by the water was the same house where Tiwazzo and J.Uclide had raised 4 of their 5 children, Tisolay’s sisters and brothers, in the 1890s.

But one day, I arrived at the tree to find that an animal had dug a hole near the foundation piers and left a huge mound of yellow sandy dirt over a foot high next to it. On top of the mound, brought up from the very bottom, was a heavy shard of blue and white crockery a little wider than my fist, almost an inch thick, obviously from something heavy-duty utilitarian. Maybe a nutria; I’d found a nutria claw once in the run-off creek bed on the other side of the pasture.

I guess it was my imagining that I were standing about where the back door of the house would have been, the work area between the house and the bayou; imagining the laundry being done, with its boiling pots and lines for hanging, cleaning fish and game down at the water’s edge, a long table and benches over there under the trees where the women probably sat with friends and did their sewing and food prep and the men whittled small household tools and toys, a spinning wheel up on the back porch off to one side, and, regarding the mystery shard, a large crockery container for whatever occupation required mixing or storage in a piece of crockery this big. I guess it was then, when I first imagined looking out at all these activities, that I realized it had been Tiwazzo’s house, because I found that it was Tiwazzo’s eyes that my mind’s eyes had been looking out of.

For 25 years, up until this week (June of 2014), I have pictured this big chunk of crockery belonging to a heavy cylindrical straight-sided crock, a good foot around or more, except, at the same time, I’d always thought there was something about its curve that didn’t fit. This past week, though, writing this post, this 19th century backyard work scene from 25 years ago came back to me, with the spinning wheel stored up out on the back porch to one side, out of the rain, and I remembered where it was I’d seen a spinning wheel, always to one side of a back porch like that… at one of Vermilionville’s* old restored Acadian houses. I also remembered what it was that had kept that spinning wheel company on the opposite side of that porch. I made a bee-line for a fresh google page and entered “19th cent butter churn, ceramic, photo”. . . and there she was, pretty as a picture, blue stripes and all. . . . Call me weird, but this sort of thing excites the stars out of me.

(Vermilionville is an open-air living history and folklife museum in Lafayette which has moved and restored many old traditional Cajun houses onto its gorgeous 23-acre site at the south end of Lafayette. This is a shameless and unapologetic plug for the place; Run, don’t walk, to spend an enchanted few hours there if you’re ever in the area.)

________________

.

There was often something about that spot under the old oak, something that made one visit stand out from the next, like that big ceramic shard.

Sometimes it was an event.

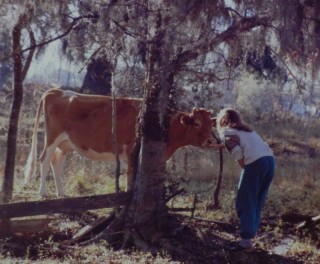

The oak tree sat at the top of a gradual slope, at the high water mark, and on the side facing the water, all the soil had been washed out from under it back to the taproot, leaving a suspended shelf of roots as a ceiling for quite a roomy space beneath; a hobbit habitat if ever there was one. Well, I often bought bags of carrots and apples at an outdoor market at the Four Corners in Breaux Bridge on the way to the farm for whoever was grazing on the property, and once, the animal I was feeding, unbeknownst to me, was a young uncut stallion who did not take “I don’t have anymore!” for an answer. I got up on the roots and hugged the trunk when his tantrum started escalating, but in the end, the only place on the farm where he couldn’t get to me was under those roots.

.

Sometimes it was Nubie, my Abyssinian cat who was so old that her habit of not eating whenever I left town was now more of a serious threat than it had been before. I soon realized that she preferred making the trip from New Orleans with me, curled up in my lap while I drove, to being left behind, and thereafter, she often went with me to the farm. Sometimes I’d bring a bag of books and study while she, an indoor cat back home, wandered the edges of the blanket happily, sniffing new things, purring in the sunshine.

.

.

.

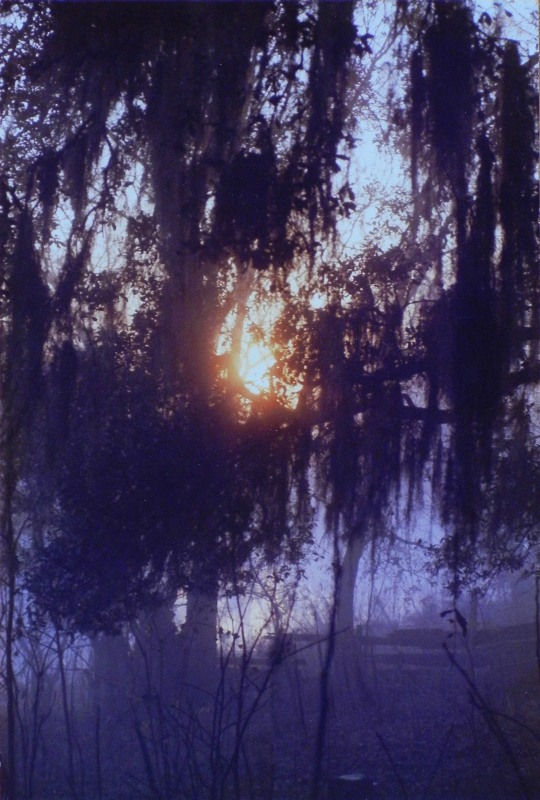

Sometimes it was a visual, a new view of something old. Occasionally, I’d come in the evenings, make a fire, and stay overnight in a small tent I kept in the back seat. Once, when the seasons were just changing, I was awakened by the shivering of my own bones, chilled by a fog so thick, it was like rain that had decided at the last minute not to hit the ground, but instead to dance a slow swirling waltz just over it. When I lifted my head, the first rays of dawn were just oozing around the bend through the mist and the moss, and I wondered how many times Tiwazzo had looked out her back door at the beginning of her day and seen exactly that.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The house on Bayou Teche:

Sometimes it was a visit to the cousins that made me see Tiwazzo’s oak tree corner in a different light. My visit to the woman who showed me the photo of Adeo’s house was certainly like that with the back square across the highway, except that it wasn’t what I had expected for an Acadian house built around 1870. Where was the tall roof and garçonniere, the front porch staircase?

Here; I’ll show you what I’m talking about.

Traditional Acadian houses have distinctive rooflines whose broad flat side slopes forward, extending far out over a deep front porch, shading it from the blazing sun. It also swoops up unusually high and steep, since it houses a garçonniere within it, an independent apartment for the older boys (garçons in French) in the family that has its own entrance via a very steep exterior staircase through the porch ceiling, squeezed into one side of the porch out of the rain. Sometimes the outline of the beams and bousillage could be seen, protected from the weather by only a coat of paint.

Well, one day Tisolay’s cousin, our neighbor to the north, took me to see her mother’s house down by the water, the original family home that both she and her mother had grown up in. Built in the 1880s by her grandfather Honoré Babin, close cousins to both Adeo and Ada, her mother had lived there through both her childhood and her married life, and had only recently died. The place was being packed up in preparation for its dismantling. One of the last of its kind, it had been sold to someone who was going to move and restore it. It was the first time I had ever been inside a traditional 19th-century Acadian house, outside a museum setting, anyway. And though the inside looked like a time capsule from WWI; wallpaper, linoleum on the wood floor, primitive electrical lighting, it was still obvious how much older the house actually was. The wavy, uneven surface beneath the decades of layers of wallpaper was plainly bousillage, crumbled and missing in places where little tendrils of moss spilled out from the patches of exposed lath. The small bathroom, awkwardly cut from a room that had once been a good bit bigger, had plainly not been part of the simple four-room house’ original design, which put the privy outdoors. And the narrow staircase, placed so steeply against the wall that it was scary just to look at, looked like it could have been the original front-porch garçonniere staircase, which were notoriously hazardous. Hmm, I never saw the front porch to see if the stairs were still there or not.

I didn’t get a picture of Honoré’s place, but I got his great uncle Narcisse’s, who was Ada’s uncle and Adeo’s great-uncle as well. Narcisse Thibodeaux, the uncle of Uranie, Honoré’s mother, was also the brother of Marie-Thersile “the intrepid”(Ada’s mother) and Marie-Amelie (Adeo’s grandmother). It was a real slice of history built around 1820. Still is, thanks to Acadian Village, the older of Lafayette’s two historic village museums which have moved and restored as many of the few remaining old Acadian houses as they could.

Anyway, it was after seeing Honoré’s house that I began to wonder why Adeo hadn’t built his house in the old style. I had always assumed by the way the elder cousins talked that the house up by the road was Adeo’s original house, and that he had built something down by the water for his daughter 20 years later when she married. But the more I looked at the photos of the house up by the road, and how its style did not incorporate the most salient features of traditional Acadian architecture [go to pg.1 of 5 for a reminder], the more I began to wonder whether the house by the water under the great oak was the original house, like Adeo’s uncle Honoré built next door.

I wish I knew whether Adeo built the second house up across the road when his children were still small, say, because there was a problem with the old house, like being prone to floods, or whether it wasn’t until his daughter married a man who wanted to join him on the farm, living and working with the family. If he were smart, he’d have waited until after the wedding when her new husband would have been on hand to help with building the second house. I wish I knew why, once built, he didn’t give the new place to Alicia, and he and his wife together with Adrien and Mathilde stay put, unless there was something about the old house that had made him want to move anyway. The cousins had always described the waterfront house as being beat-up, damaged by several bad floods in the 20s, and only used by Adeo’s farm workers. Since the wedding was in May of 1890, and the census for the decade taken just a few months later, it would have been interesting to see whether they were all still living in a single household, or whether the 2 separate households we see in the 1900 census had also been established in 1890. But the US census of 1890 was destroyed in Wash. D.C. by a fire in 1921.

Regardless of when the two houses were built, though, the land itself seemed to point to the waterfront square of land being the setting for the original house, as it still bore signs of ancient cypress fencing, as well as remnants of a large front gate up by the road. The back square across the road had no such remnants. In fact, I pictured there being no back square, that the crops started right at the road.

The truth is I don’t know, but it no longer mattered. My little spot under the oak where the foundation cones lay had changed in significance again, becoming, regardless of proof, the site of the elusive original home Adeo built in 1869 after inheriting the land from the mother he lost when he was only 5, the home he brought Ada home to when they married, the classic old Acadian house I had always imagined it to be.

_________________________________

And then sometimes it’s just a photograph.

It has always been hard for me to put words to how I feel about this piece of land. But one time I brought along a friend who, without my knowing it, collected branches from the pecan tree, the cedars and the oak, took them home and carved two chopsticks from each one for my hair. Knowing of my great connection with Tisolay, he also carved, from a single branch(!) a chain of links with my initial at one end and Tisolay’s at the other. When he gave them to me, he also gave me this shot which I hadn’t know he’d taken. After that, I didn’t need to look for words anymore to show how I felt about this place; this did it for me, perfectly.

.

.

Go on to pg.4 of 5 or Return to pg.2 of 5

and as usual,

Thanks so much for your interest in my funny Tisolay’s story.

© All rights reserved – postkatrinastella.com

.

.

.

Hello,

My name is Donald. This note comes in the wake of a phone call I received last night (7/30/2014) from my cousin, Ashley in Liberty, Tx.

She gave me the link to your website. The pictures you have documented are all familiar to me. As a child, I frequently played “house” with my first cousins. I have been doing some research on my side of this family, the black side. Our property is right adjacent to the property you describe. How I wished you had talked to some of the black family members during your visits in 1989! I hope to meet you some day, perhaps on your next visit.

Love the photos. I make clay sculptures with bark textures and knots. I stumbled across your site while googling live oak root knots. Glad to see there’s someone else out in the world who loves these.